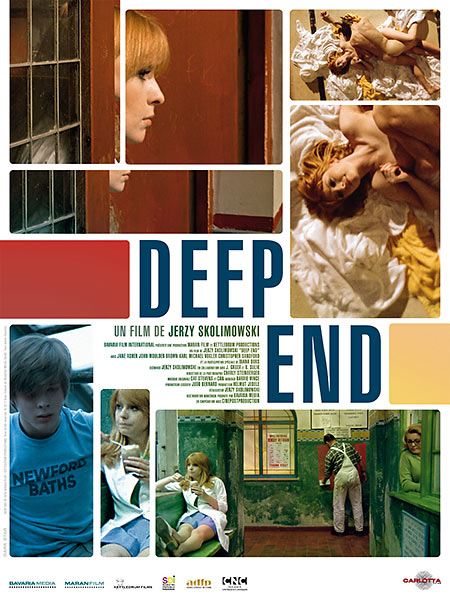

Directed by: Jerzy Skolimowski

Directed by: Jerzy Skolimowski

Writing Credits: Jerzy Skolimowski, Jerzy Gruza, Boleslaw Sulik

Director of photography: Charly Steinberger

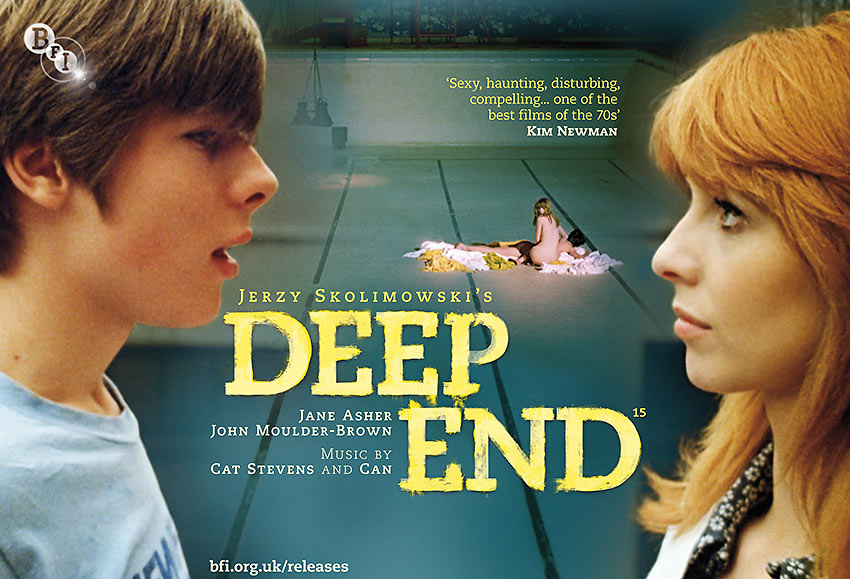

Cast: Jane Asher, John Moulder-Brown, Karl Michael Vogler

Jerzy Skolimowski’s

Deep End

By Walt Mundkowsky

Deep End (1970, Paramount) is Jerzy Skolimowski’s seventh film, but the first to get a run in these parts. In 1968 Christian Braad Thomsen called him “probably the most explosive and original film-maker in Eastern Europe.” That is a bit much (Jancsó? Makavejev?), but his work is important and Deep End is representative of it.

Skolimowski is a very interesting fellow. An ex-boxer, he brought out two volumes of poems and a collection of short stories at 22. He wrote dialogue for Andrzej Wajda’s Innocent Sorcerers, a bitter look at modern Polish youth, and Polanski’s Knife in the Water. I have not seen Skolimowski’s first two features. He enrolled in the Polish State Film School in 1960; he says, “I was seized with a great uncertainty. I was afraid of botching everything, of being a zero, or of spending long obscure years at being an assistant, which was scarcely better. Before those sad possibilities for the future, I began to ask myself how the devil I could get out of the situation.” He made his short films at the School in such a way that, once assembled, they would form a full-length film — Rysopis. Cahiers du Cinéma described Walkover, his second, as “one of the most rapid films that can be seen, crammed with things that one must seize in flight, or by deduction” — all the more remarkable because it was shot in very long takes: The 78 minutes contain only 35 cuts. Barrier was impressive: a precarious love affair and a ferocious criticism of Polish society. It is scornfully accurate about the chasm between those who remember the Nazis and the young people who don’t, and don’t want to. Skolimowski has a vivid eye for framing and imagery: crisp, laconic, nimble, tossed-off. In 1967 he made Le Départ in Brussels without knowing any French at all; the improvising got so anarchic that he required two interpreters to tell him what the actors were saying. Hands Up! was banned in Poland, and The Adventures of Gerard, adapted from Conan Doyle’s Napoleonic War stories, was another casualty. It sounds like a film that defies classification, which distributors hate.

Deep End also evades neat categories. Ads suggest a horror thriller like Repulsion, and the opening plays on and frustrates that. The first titles appear in red over a gray background. A drop of blood, enormously magnified, hits the gray and runs towards the bottom of the screen, which turns red as Cat Stevens wails, “But I might die tonight!” Geometric camera movements follow tubing, gears, chains. The blood turns out to be paint: a boy painting his bicycle. The gray background is the bicycle in extreme close-up.

The story takes place within about a week — longer than usual with Skolimowski. Mike, a 15-year-old who has left school, gets his first job — attendant at a public bathhouse and swimming pool. He quickly falls for Susan, a sexy, somewhat older girl who looks after the women’s section. She is amused by his attentions and alternately entices and abuses him. Mike slips over the edge into lunacy — a mad crush gone truly mad — and Susan fails to realize the lethal nature of his attachment.

Its triumph is that, as Charles Thomas Samuels writes, the “meaning is absolutely conterminus with its form” — observations and style are one. The agile hand-held camerawork reflects the characters; fidgety walking pans and tracks match the restlessness of the people. Skolimowski does not want to analyze or explain love and its workings, he is after metaphors for states of feeling. The bathhouse is almost too good to be true; supposedly used for cleanliness and recreation, we see a succession of sexual rites: an elephantine blonde associating soccer and screwing, a coach feeling up the schoolgirls in his swimming class as he guides them into the water, the boys’ dirty remarks about Susan. The place is done up in hideous green, yellow and blue tiles. “I thought it would be all white,” Mike says when Susan shows him around, and it is only the first of his idealized views to be thwarted. Susan coaxes a dog in the park closer, then stings it with a snowball — exactly what she is doing to Mike.

The closing minutes form an ever-tightening pattern. Mike sabotages the tires on the coach’s car, which Susan is driving. She gets out and gives him a sound thrashing, but loses the diamond from her engagement ring in the process. They cannot find it in the snow. Mike comes up with an idea, childishly elaborate and impractical. They scoop the snow into trash bags and carry them back to the bathhouse for meltdown. As if these symbols — the snow: Mike’s original belief, now overturned, in Susan’s purity, and her coldness towards him now; the ring: the materialistic nature of her fiancé’s claim on her, and the shallowness of her affection — were not enough, Susan suggests that to find the diamond they strain the melted snow through her tights!

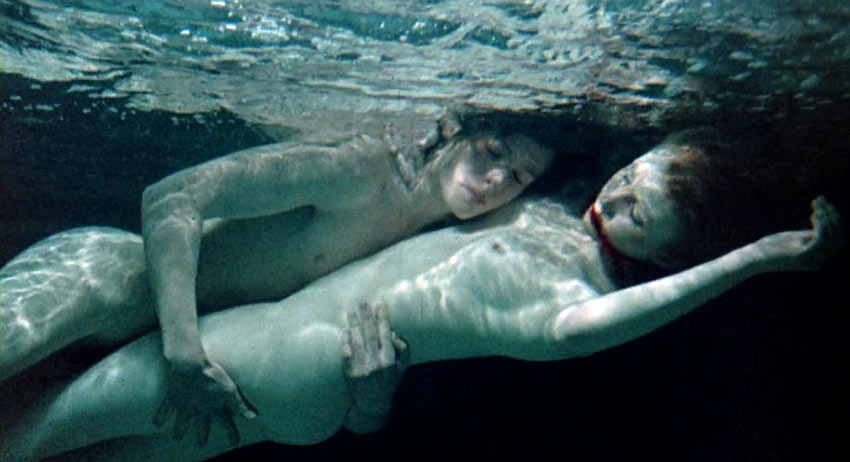

The climax carries all this to a formally — but not emotionally — satisfying conclusion. Susan leaves to call her fiancé and tell him she will be late. When she returns, Mike is lying nude under a pile of towels with the stone in his mouth. As a reward, she offers herself to him but he seems unable to perform. She wants to leave; he wants her to stay and talk. The janitor is filling the pool for the next day. They struggle as the water pours in, and in anger Mike swings an overhead light fixture at her head. She faces him, stunned. The swinging light knocks over some cans, and red paint splashes down the wall and into the pool. (The spilled paint manages a more powerful effect than looking at the bleeding Susan would.) She starts to sink, and Mike clings to her as they both go under. The Cat Stevens refrain from the credits returns. Slow fadeout.

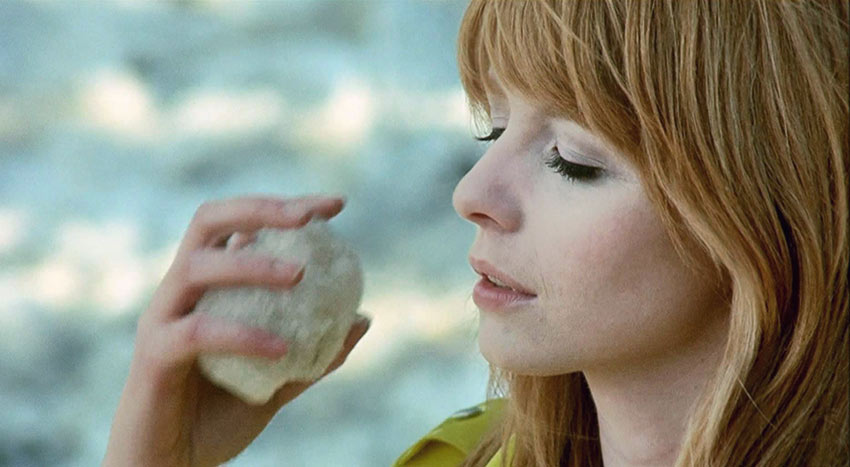

I am of several minds about this ending. It shows mastery — like Susan, Mike’s violent attack took me by surprise — and some shots hit home (her yellow vinyl maxicoat sinking beneath the surface). But it’s also monumentally contrived, and the skill lavished on it diminishes the characters, indeed the entire film. Coolness bordering on freakish has always been a part of Skolimowski’s style; here it unsettles, as I wonder if he takes these characters less seriously than I do. Susan is perceived with horrible sharpness, and Jane Asher’s performance fits the contours of the character so exactly that it does not seem acting at all.

Mike’s reactions are muddled: He idolizes her, yet wants to possess her. One brief, penetrating scene makes this clear. Susan is beside the pool in a black bikini, eating lunch. Several schoolboys are ogling her. Mike batters one boy who knows him, but he has been thinking the very same thing. The boys throw Mike into the pool and, under the water, he imagines Susan gliding past him, naked.

Later, he sees a life-sized cutout in front of a nudie theater; the girl looks something like Susan, and Mike steals it. He confronts her with it (on the subway!), visions of her innocence severely dented — “No, you’re not like this, Sue!” She deadpans, “Oh no, I’m much worse than that.” He throws his surrogate Susan into the pool, undresses, and dives in after her. The editing transforms his tussle with the cardboard lady into a fierce imaginary copulation with the real Susan.

John Moulder-Brown is good as Mike — the right look and voice, and he handles most of the various swerves fairly well. The film’s viewpoint wobbles, and at times we are invited to share Susan’s valuation of him: an insignificant little punk who is fun to toy with.

The usual Skolimowski gifts are very much in evidence. Charly Steinberger’s color photography conveys even the smells of the bathhouse; certain of the pictures are Red Desert-gorgeous without the fussiness (Susan framed against a wall painted in blotches of green and orange). Some of the gags are inspired by a uniquely Polish non-logic (Mike cuts his hand and goes to a medicine cabinet that’s empty; a painter is first seen in the background, as a disembodied arm wielding a brush). Music is central to Skolimowski’s art, and Deep End has the best-employed rock score (by Cat Stevens and Can) I can remember — economical, haunting, relevant. Some of Can’s contribution (not enough!) is on their Soundtracks album (Mute).

I have made Deep End sound better than it is; for me it avoids so many pitfalls so well. Skolimowski films have their self-destructive side, none more than this one. The writers (Skolimowski, Jerzy Gruza, Boleslaw Sulik) are Poles, and the dialogue appears largely improvised. Scenes that depend on talk can trail off into nothing — too much like actual conversation, in fact.

A good many scenes are not as funny as Skolimowski thinks they are. In particular, a gag involving a Chinese hot dog vendor is instantly excruciating and keeps being reprised. Others are rather cheap — a prostitute with a cast on one leg, the sex-movie theater manager who calls Mike “you perverted little monster!” The film strives for lightness — to set off the ending more strongly — but its humor often stalls.

London in Deep End looks vaguely like the real thing — quite a feat considering most of it was shot in Munich, with Germans later dubbed in English in the minor roles. Some of the movie exhibits a baffling sort of carelessness; I can’t always tell when it’s bad with a purpose and when Skolimowski simply can’t be bothered.

But I would not like to end on the negative. Deep End has its flaws, some of them large, but it proceeds from a vision of the world and a personal signature. He stacks the cards against himself unmercifully on this occasion, but he succeeds in his goal — to express a character’s obsession in poetic terms.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.