By Ed Boitano; Photography by Deb Roskamp

The sound of the tracks was calming as my railway car glided effortlessly through Northern England’s breathtaking countryside. Watching the miles pass from a train window allows a perspective that is not offered by plane travel. And now, heading to Carlisle in Cumbria, nothing else seemed to matter besides the little farms, lakes and villages dotting the sweeping green fields of England’s North. My spell was slightly broken when an elderly gentleman beside me, offered a soft-spoken narrative of its history, a history where the gentle green fields were once soaked in the color of red. Yes, the conquerors and the conquered: the Celts, the Romans, the Angles and Saxons, the Vikings, the Normans and the Boarder Reivers; who had all shed their fair share of blood in the northern fields. But it was still difficult to imagine with Northern England’s ethereal landscape before my eyes.

It felt good to rest; after all I had packed it in for the last two weeks in London: The British Museum, the Tates, the Garden Museum; the Churchill War Rooms; The East End; Macbeth at the Globe, plays in the West End, along with a considerable amount of pub grub and pints of bitters. And, in the next three days it would be Carlisle, its city center, museums, cathedral and castle.

Carlisle, Cumbria, England – A Cathedral City

Upon my arrival at the Carlisle railway station, I noticed the towering twin drum bastions at the Citadel built by Henry VIII in 1541. The guidebooks said that it was essential to spend at least a few days at this historic Cumbrian city, and the Citadel seemed to promise that I would. Carlisle, spoken locally as ‘ka-rlail’ or ‘KAR-lyle,’ is located in the county of Cumbria, England, and has the distinction of being a cathedral city – a title granted by the monarch of the United Kingdom awarded to a town in the UK having a cathedral within its bounds.

The early history of Carlisle stems from its establishment as a Roman settlement to serve forts along Hadrian’s Wall. Carlisle – the Latin name of ‘Luguvalium’ – was the most northwestern settlement in the Roman Empire; an important frontier town on the edge of its empire.

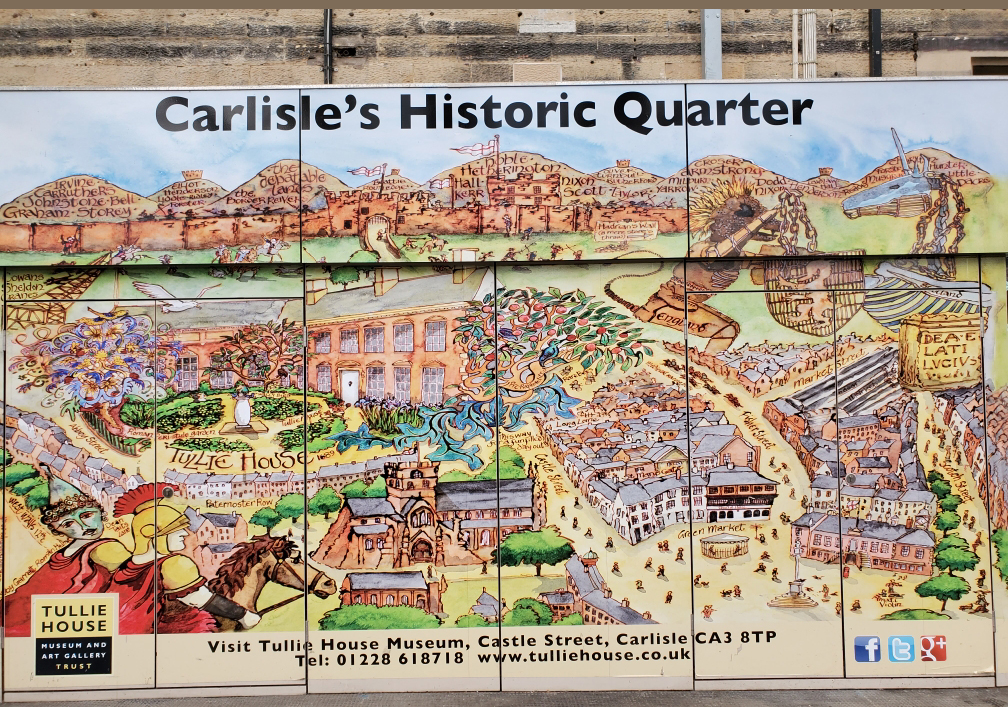

Later, due to its proximity to the Anglo-Scottish border, Carlisle became an important military stronghold in the Middle Ages. Then new migrants from as far away as Wales and Cornwall poured into Cumbria to toil in its rich mines of iron ore and copper. Carlisle transitioned again as a bustling industrialized town of factories at the advent of WW1. The Border City took a hit with the closure of its industries. But it eventually rebounded as a mecca for tourism, a mecca which included a well-designed Downtown Historic Center with museums, antiques and art galleries; the imposing Carlisle Castle; the Tullie House Museum and the Carlisle Cathedral.

I found Carlisle’s younger set to be warm and welcoming, curious where you were from and why you chose to visit their city. My immediate reply was to spend a few days in Carlisle and then head off to Hadrian’s Wall for a full day. I couldn’t help but notice that some were not impressed about my plans: ‘That’s a lot of fuss for a bunch of rocks,’ ‘Not too tall, innit.’ It appeared that they had little interest in the history of the Wall, a UNESCO World Heritage site, just 33 miles or so up the road from where they live. I still don’t really know the reason why. Jealousy, perhaps? But how could it be jealousy when a tourist trip to Calisle also meant visiting the Wall. Yes, I still don’t really know the reason why.

Click here for Cumberland sausage recipe.

The weekend nights in Carlilse would explode with excitement, in particular when one of the local sports teams won an important match. Post-adolescent groups of men and women would charge from pub to pub, leaving only a trail of vape smoke behind them. Their selection of clothes worn served almost as if they were on a runway, illustrating the current Carlisle fashion trends of the day, which were confirmed with each style almost identical to the next.

Downtown Historic Carlisle Center

The Downtown Historic Carlisle Center was within walking distance of my lodging property, The Halston Hotel Carlisle, whose manager and staff were never too busy to point out local attractions. It was recommended that a good way to start a self-guided tour is a stop at the Cumberland Valley Visitors Center, which features maps, brochures and a very informative staff.

Next was the Carlisle Historical Society at the Heald House Museum, which also offered a wide-eyed lens on all things Carlisle. With its Old Town Hall clock tower and market cross, and the array of cafes, art and antique galleries, made it clear that history and culture defined the Downtown Carlisle Center of today. And, just a short drive outside of downtown is the Carlisle Barracks, that features more than 100 historic buildings, 22 of which are listed on the British National Historic Register. It was suggested that I should end my day-long journey by visiting the Trout Gallery at Dickinson College.

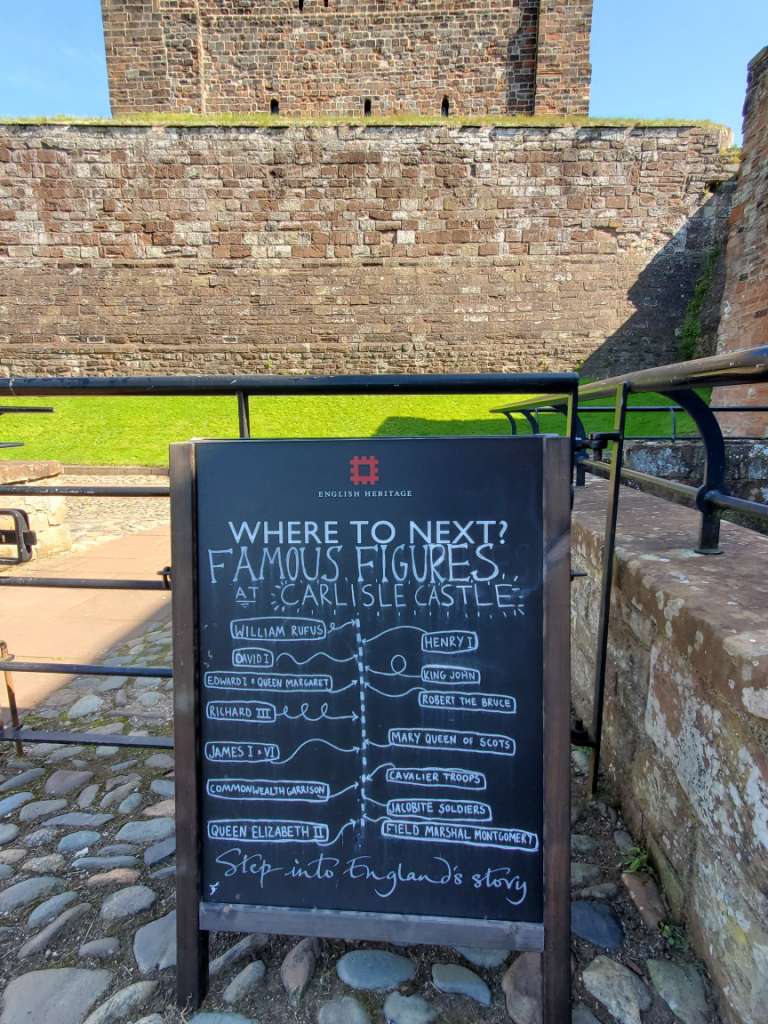

CARLISE CASTLE

Carlisle Castle, located on the edge of the downtown center, is a restored medieval fortress; the site of many sieges, public executions and political discourses throughout its 930-year-old history. Like Carlisle itself, it was built on the former Roman site of Luguvalium, during the reign of William II of England, the son of William the Norman Conqueror. The castle has been besieged ten times – more than any other place in the British Isles. Its walls were predominantly made with grey and red sandstone, and overall constructed in the Norman style of a Motte-and-Bailey castle; raised earthwork is called a ‘motte,’ and ‘bailey’ means an enclosed courtyard, all surrounded by a protective ditch and sharpened vertical stakes or palisade.

During its tumultuous history, the castle changed hands many times between the English and Scotts. It also served as protection from the Border Reivers, malicious bands of cattle rustlers who would kill anyone in their way, sometimes just for the fun of it. The last battle at the castle was the failed Jacobite rising of 1745 against George II. The battle marked the end of the castle’s years of fighting, for defending the border between England and Scotland was no longer necessary as both countries once again flew under the same British flag. But the real final act of bloodshed at the castle was the mass execution of Jacobite prisoners, with those remaining either shipped to the West Indies as slaves or banished in exile. Charles Edward Stuart, the proud Bonnie Prince Charlie, who had united the Highland Clans and orchestrated the rebellion, avoided capture by hiding in modest Highland homes, eventually sailing to safety in France, disguised as a woman.

As we parked our rental in the car park, we spent a few minutes trying to understand what a large sign meant: ‘No Fly Tipping.’ We were approached by a kind family from Houston, who were also curious to its meaning. But then I remembered that we had a small mechanical device in our pockets, and by simply accessing it found that it meant ‘no illegal garbage dumbing’: ‘Fly’ originates from ‘on the fly’, i.e., an act carried out while on the run, while ‘Tipping’ refers to dumping your rubbish at a ‘council tip.’ And these are the people who gave 25% of the world’s population the English language. Once the confusion was settled, we strolled to the castle, and the sun was out and the well-manicured lush green grass made it hard to believe that this gentle piece land was once site the of blood and carnage. The exterior of the castle, with its draw bridge, deep mott and Irish/Caldew Gate immediately grabbed my attention. Little did I know that this would be the highpoint of my tour.

Past the gate, the outer ward courtyard consisted of a large spread of unremarkable flat land which I had thought would illustrate what life was like for its occupants of the past. The guidebook stated that the courtyard was once centered on a tarmac-covered parade ground in a field of grass, and, due to its huge space gave the castle the capacity to house spectacular events of marching brigades and festivities. Yes, the garrison was still there, but I realized, like many things, this piece of history had become the history of now.

There was much restoration inside the inner walls, due to another form of besiegement: climate change. It’s a current problem in Britain today, as it is throughout the world, where historic buildings and schools are beginning to crumble. For historians, restoration is of the upmost importance, but for the fearful children and occupants inside, it is nothing less than essential. After climbing the stairway to the second floor, we had expected to explore the rooms where Richard III, Bonnie Prince Charlie and the imprisoned Mary, Queen of Scots once slept. But it turned out to be one large room, though a Great One, with another sign listing the many who had once called it home. The room, however, was in period décor with a massive fireplace, tapestries and furniture; and a smaller room upstairs featured a bed where hay, sandwiched between two coarse sheets, illustrated the makings of a comfortable medieval night of sleep.

Also on the second floor was a group of carvings entrenched into the stonework. The guide book referred to them as ‘prisoners’ carvings,’ but this area of the castle was not known to have been a prison. The carvings seem more likely to be the work of members of the castle’s garrison or household, perhaps expressing loyalty to the lord warden and great local families.

For an extra price, I toured the castle’s small Cumbria’s Museum of Military Life, which showcased the history of Cumbria’s County Infantry Regiment, the Border Regiment and the King’s Own Royal Border Regiment and local Militia. The war artifacts were stimulating, but it was the narrative at each station and a short video that made it worthwhile.

The Tullie House Museum

The Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery (circa 1893) features exhibits detailing the history of the Roman occupancy and Hadrian’s Wall. The treasures inside also include zoological, botanical and geological artifacts, stringed instruments, including a violin by Andrea Amati, an art collection with works by pre-Italian renascence artists, and post-Roman history, dedicated to the Vikings and the Border Reivers.

All Roads Really Do Lead to Rome

It was at this point of my tour, I realized that everything I had seen and everything I had done all led to the Roman Empire; which is a subject I’ll address in the next installment devoted to Hadrian’s Wall.

Carlisle Cathedral

Carlisle Cathedral made a refreshing reprieve from the death and unfound glory I had experienced at Carlisle Castle. Nestled on a peaceful gated street in the city center, it was founded as an Augustinian priory and became a cathedral in 1133. It is also the seat of the Bishop of Carlisle. Over 900 years of history is on display within its stunning mix of Norman and Gothic architecture, medieval paintings, delicate carvings, intricate stained-glass windows, and most importantly, the starlight ceiling; considered the most significant architectural feature of Carlisle Cathedral. It was difficult not to feel emotionally taken while sitting beneath it during choir and worship music.

Carlisle Cathedral also has a set of 46 carved wooden choir stalls with misericords, hinged seats, “constructed to keep the monks from falling asleep while at prayers.” The pillars supporting the canopies indicate that some portions had once been burnt, some assumed to be by raiders, but actually burnt by monks who fell asleep during their long devotions while holding lighted candles. Intricate iconographic carvings in the misericords still remain with the narratives of St. Anthony the Hermit, St. Cuthbert, St. Augustine, the twelve apostles, as well as the inverted ‘world theme’ of a Woman beating a Man, which I was told that no decent set of misericords could be without.

I noticed many of the congregation during the Sunday service wore period costumes, but were not intended to be docents, simply warming to the theme of the cathedral’s past history of dress. I also noticed that this Sunday service was almost empty of occupants. Perhaps indicative of western regions now focusing more on secular ideals. But if you’re religious or not, Carlisle Cathedral is worth a visit.

POST SCRIPT: How could I have forgotten

Yes, how could I have forgotten that a few days earlier I had taken a stroll over Westminster Bridge. The 827-foot-long road and foot traffic bridge is one of 138 bridges that stretch over London’s River Thames. On its far north side rests the Houses of Parliament where it boasts the highest number of arches among all Thames bridges. Decorative ironworks showcase the symbols of parliament and the United Kingdom: the cross of Saint George, a thistle, a shield, and a rose. Octagonal Gothic lamps line the bridge, and in the middle there is a small plaque with a William Wordsworth poem, appropriately titled ‘Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802.’

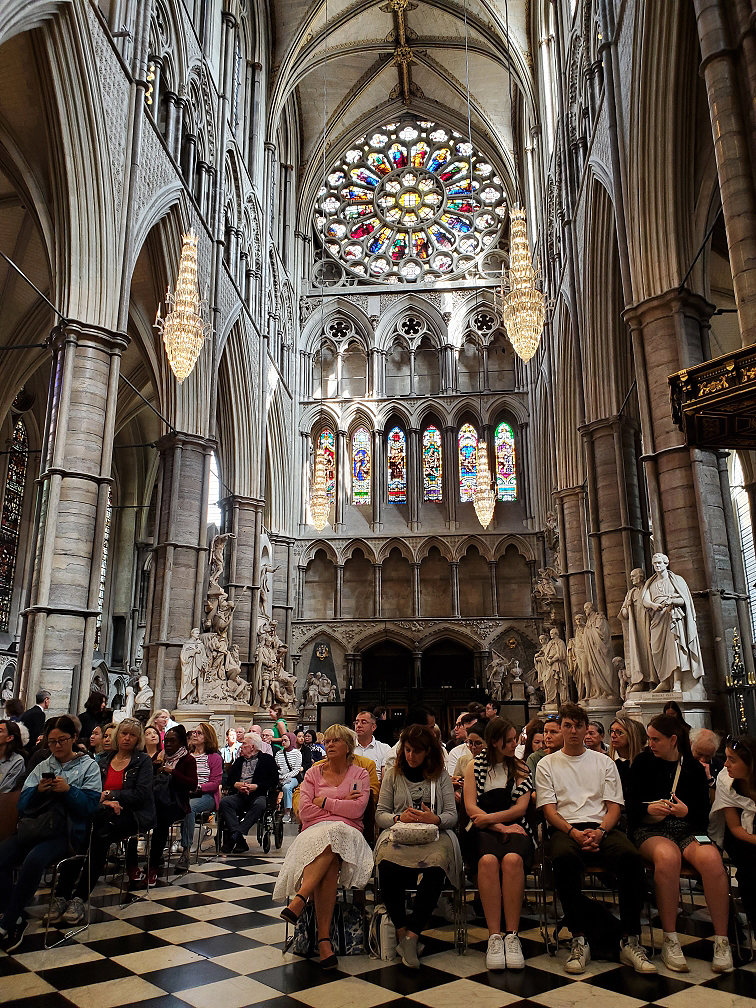

But it was at this point of the day, the day before my departure to England’s North, I remembered that I’d forgotten to write about something that most tourists to London generally have on their to-do-lists: Westminster Abbey. Its Sunday service I had attended would make an interesting comparison to my later attendance at Carlisle Cathedral, which I had scheduled the following week and had written about above.

Westminster Abbey

It was difficult not to think of historic grandeur at the Anglican Westminster Abbey, the location of 40 English and British royal coronations, the burial site for 18 English, Scottish, and British monarchs, and 16 royal weddings since 1100 ACE.

I was surprised to read that the origins of the church are obscure, where it had once housed 10th century Benedictine monks, and throughout the 21st century, non-monarchical prime ministers, poet laureates, actors, scientists, military leaders, and then, most importantly, the Unknown Warrior. Yes, may we never forget. And may we also never forget the Unknown Citizen, whose death may have come from the Unknown Universal Soldier. Their pauper gravesites are not surrounded by the grandeur of Gothic style architecture, and there are no long lines of people expressing heartfelt sympathy and admiration. History generally covers only the lives of the famous and the wealthy; the rest of us are pretty much on our own.

Dissolution and Reformation: Blame it on Henry

In the 1530s, Henry VIII left the Roman Catholic Church and anointed himself the head of England’s monasteries. It was the beginning of the English Reformation, though slightly different than the Protestant Reformation which had swept through continental Europe a few decades earlier. The German-Roman Catholic priest and theologian, Martin Luther, spearheaded the movement by attacking the Papacy due to the church’s corruption. He never officially broke from the Roman Catholic Church, but the Papacy broke with him when he was excommunicated in 1521.

It should be noted that the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century was not unprecedented where reformers within the Roman Catholic Church such as St. Francis of Assisi, Valdes (founder of the Waldensians), Jan Hus, and John Wycliffe addressed similar problems in the church in the centuries before 1517.

With Henry VIII’s eventual departure from the Roman Catholic Church, it was something a little less righteous than the Protestant Reformation, where he sought to annul, not divorce as commonly assumed, his first marriage to the Spanish Catherine of Aragon. Henry had married Catherine due to the Tudor tradition of marrying the wife of an older brother. In this case, the older brother was Arthur, Prince of Wales, the eldest son of King Henry VII of England, the heir apparent of the crown. Catherine was three years old when she was betrothed, but Arthur met an untimely death at age 15, shortly after his marriage to her, a marriage that was never consummated in the bedroom.

In 1509, after Henry VIII was crowned the King of England, Catherine never produced the desired male heir for the new king, only a daughter, who would eventually become Mary I, the first undisputed English queen regant in 1553. It is believed than Henry saw his daughter just once during his lifetime, which consisted of a distant royal bow from the courtyard of Kimbolton Castle to a castle window where she faced down upon him.

Henry remained steadfast to marry a second wife. Her name was Anne Boleyn, who had been Catherine’s maid of honor, a junior attendant of a queen in the royal household. She was also pregnant with his child. The Papacy in Rome wouldn’t recognize his request, and Henry eventually had run out of options. So he he left the Roman Catholic Church, and Catherine was banished from the Royal Court, and lived out the remainder of her life at Kimbolton Castle, dying of cancer in 1536. It was a day of mourning throughout England for Catholics or not.

Anne Boleyn would eventually become Henry’s new queen consort, his second wife out of six, and after a series of miscarriages, the mother who gave birth to another little girl, this one named Elizabeth, again not the son and heir that Henry desperately wanted. The little girl, 28-years later, became Elizabeth I, the Queen of England and Ireland, the ‘Virgin Queen,’ the last monarch of the House of Tudor. The two half-sisters: Mary, a devout Catholic, and Elizabeth, a staunch Protestant, would meet again later which would end in tragedy, a tragedy still spoken about today.

Henry was well aware that the Roman Catholic Churches throughout England were riddled with corruption and flush with gold, and didn’t hesitate in fattening his own purse by taking many relics, images of saints, and treasures from the abbeys. His lust for gold reached such a fever of intensity that he melted down the golden feretory that housed the coffin of Edward the Confessor. Many parish priests were banished without a coin in their pockets; others met death from the sword.

The circumstances regarding Henry and Boleyn’s short marriage (1533 to 1536) and Boleyn’s execution by beheading for treason, still remains a mystery today. Nevertheless, Boleyn continues to be a key figure in the political and religious upheaval that marked the start of the English Reformation.

For more on Henry, visit his life at Hampton Court Palace

The monastery was dissolved in 1559 and the church was made a royal peculiar, responsible directly to the monarchy. The Abbey received a financial grant from Parliament in 1697. Sir Christopher Wren, who ultimately designed 53 London churches, including St. Paul’s Cathedral, was appointed Surveyor of the Fabric at Westminster Abbey on 1698, which allowed him to undertake major restoration of the decayed stonework of the church and its roofs.

In 1987, the abbey, together with the Palace of Westminster and St. Margaret’s Church, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site because of its historic and symbolic significance.

Stay tuned to Part 4: Hadrian’s Wall and the Roman Empire, and tour guide extraordinaire, Mr. Peter Carney. It would prove to be a holy day of a different order.

Raoul

November 21, 2023 at 7:04 am

What a great article. Northern England – not a lot of tourists go there. The pictures and the well-researched data is quite impressive. This is how history should be taught in schools. I’m glad those old castles have been preserved. Such high walls. Imagine the activity along the walls. Was there a marketplace? Were there guards marching or were they strolling about leisurely?

Again, bravo! Great piece!