Story by Anne Z. Cooke

All photographs courtesy of Steve Haggerty/ColorWorld

RARATONGA, Cook Islands – It was a quiet afternoon on Raratonga, in the Cook Islands, when Lydia Nga heard the news. With the stroke of a pen, her homeland, 15 scattered islets west of Tahiti, a country smaller than Detroit, had grown exponentially, reborn as a 690,000 square-mile nation.

But it wasn’t the islands that grew. In 1982, the Third United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea ruled that coastal nations had jurisdiction over their own “exclusive economic zone,” defined as 200 miles of the ocean floor, measured from the shore. Most nations welcomed the ruling. For a group of tiny islets like the Cooks, population 17,600, it was a passport to the future.

Fast forward to my second visit to Rarotonga, lured by memories of blue lagoons, warm breezes and fewer annual tourists than DisneyWorld sees in a holiday weekend.

“How’s the economy doing?” asked my editor at the newspaper. “Has big money spoiled Rarotonga’s Polynesian charms? The last time we looked the Cooks were like Hawaii in the 1960s, 50 years behind everybody else.”

I wondered myself. And as the overnight flight from Los Angeles descended above a group of low, volcanic peaks, the lagoon and its sandy shoreline, framed by rows of palms and scattered houses, came into view. Adjusting to a new time zone, I figured I’d start the day on the beach with a stroll and a swim. But Nga, head of the tourist office, better known as Auntie Lydia, greeted me with a resounding “welcome” and a request.

“I hope you can stop at the Marae Moana office to meet our ocean specialist,” she said. “He’s the one who can explain what the Marine Park conservation project is all about.” Greeting us at the door, the speaker, a tall man in shorts, waved us toward a couple of empty seats behind a dozen high school kids then turned back to the chart on the screen up front.

“Marae Moana means ocean domaine,” he said. “It’s a mind-set, an idea, a shift in the way we see ourselves,” he added, clicking through a series of charts listing each of the Cook’s 15 islands and regulations including fishing areas, no-fish areas and sea-bed limits. “We’re may be from different islands, but we’re one marine nation,” he said. “As conservators of 690,000 square miles of ocean floor, including known and untapped resources, we need to know that the government will be conducting a detailed survey of it all.”

Slipping out, I headed to the nearest ocean-side café for a grilled fish sandwich, and sharing a table, I made two new friends. Friendly and curious, they explained that the Cooks have a historic connection with New Zealand, and many have families there. Yearly visits are the norm and most college-bound students choose a school in New Zealand or Australia.

Later, at dinner at the Moorings Café, I learned that New Zealand’s Maoris originally came from Rarotonga. Falling out with a rival clan, they loaded their families onto canoes – ocean-going “vakas” – and headed west, eventually settling New Zealand. Meanwhile, curious about the menu, I learned that the sea slugs listed under “Seafood,” squishy marine dwellers commonly found in shallow water, are not only a favorite snack but are often eaten raw.

At Charlie’s Café, I found myself sitting with a group speaking a mix of English (for my benefit) and Maori, one of the few Polynesian languages still in common use. A required subject in school, they told me, it lives on in the Cook Islands despite colonial rule, foreign tourists and cell phones.

The next day and ready to explore, I rented a bicycle for a jaunt on the famous “outer-circle” road, 20 miles around and “a good way to get your bearings,” according to my guidebook. I could have hurried – the road is paved – but it was more fun to stop at viewpoints, wander through craft shops and wave at passing motorcyclists. Teens, moms, grandpas, men with fishing rods, everybody was riding a motorcycle.

The tour was so rewarding that I signed up for another bike tour, this one on the “inner-circle” road, the “Ara Metua,” an ancient road said to be 1,000 years old. Guides Dave and Tami Furnell, the owners of Storytellers Eco-Cycle Tours, led the group on a sometimes-paved, mostly grassy, occasionally gravelly road encircling the base of the mountains.

Staying inland and taking frequent detours between forests and farm fields, I discovered why the food in Raratonga’s restaurants is so fresh. It’s because it’s grown locally. Rows of taro (the edible leaf variety) grew next to salad greens, tomatoes, pumpkins, red peppers, onions, pineapples and passion fruit. Blocks of orchards produced limes, oranges, papaya, mangoes and star fruit. Stopping at the noni orchard, Tami stopped to explain that the noni, reputed to be a health tonic, is one of the few fruits grown for export. Picking a ripe one, mushy, smelly and dripping juice, she held it out. “Go ahead, try it,” she said, laughing. “They’re a popular mosquito repellent.” Pulling it into pieces and handing chunks around – to a chorus of laughs and “yuck, icky, sticky” – she dared us to smear a little on.

Since no Cook Island is complete without a visit to the neighboring island Aitutaki (eye-too-TOC-kee), famed for its enormous lagoon, I grabbed a seat on the next flight, took a bus to the lagoon and checked into an over-water bungalow at the Aitutaki Lagoon Resort. Popular with families, children, girlfriends and newly-weds, the bungalows include kitchenettes and sleep up to six people. Walking paths circle the property and the restaurant serves three meals a day. With a deck and a ladder five feet away, outside my door, I had to get into the water and float around.

Since the only way to explore the Lagoon is by boat, the resort concierge suggested a cruise with Tere (pronounced Terry), an enterprising islander and owner of Te King Lagoon Cruises, one of several local outfits. Packing ten of us (from the U.S., Italy and Australia) into his boat, he circled the lagoon, speeding through deep water and rounding the motus (coral islets) on the rim. Reaching shallower water, we slowed down to drift-speed for a closer look at the spectacular coral gardens, reef fish, and all of a sudden, a couple of massive four-footers, big fish cruising among the smaller ones.

Circling again, heading for lunch at One Foot Island, we climbed out on an enormous sand bar for the trek to shore. Greeted by the smell of grilled chicken, we found the lunch crew working in the shade, flipping wings and breasts and laying out plates of fresh fruit, green salads, potatoes, bread and chips. I discovered why we’d been told to bring our passports. Those who did – including me – came away with One Foot’s famous “been there, loved it” stamp.

Speeding back to the pier, leaving a wake behind, I found myself marveling at every other South Pacific lagoon, each a unique biome inside Pacific lagoons, ecological wonders inside a coral reef. Protected from the wind and tides but continually refreshed by water spilling over the edge, lagoons are worlds unto themselves, populated by birds, fish, crabs, clams, mollusks, coral and insects. And people.

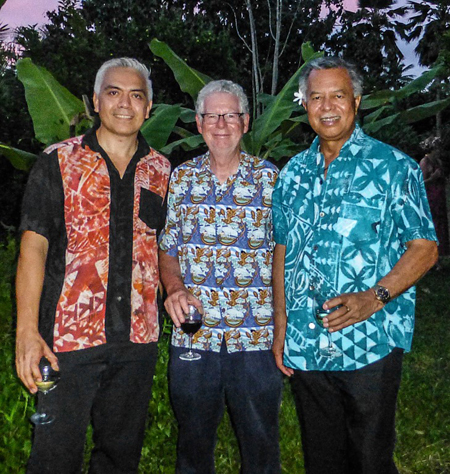

On my last evening, I was invited to dinner at Plantation House, a colonial home and the property of Louis Enoka, a former restaurant owner and international businessman. The dinner, with Chef Minar Henderson cooking, is held just once a month and seats 20 to 26 diners guests at a single table. Equally important is the pre-dinner cocktail hour, a rare opportunity for diners to wear a gown or put on a tie, introduce themselves and socialize. And it gives Henderson a chance to finish dozens of different dishes at the same time: A remarkable feast, with heaping platters of chicken, fish, pork and pasta, and plates piled with fruit, island-grown vegetables and spices. But the event has a larger purpose. It’s an opportunity for those with a world view people, whether islanders or visitors, to share their views on politics, international business, technology and science, and ancient cultures.

Filling my plate and heading to a designated chair, I was amazed to find the former Prime Minister, Henry Pun, sitting next to me. After studying law in New Zealand and Australia, he said, he turned to politics. But with dinner in front of us, serious conversation gave way to the meal, and comparing the prawns with lemongrass to the coconut-flavored rice and the spiced pork and couscous with kaffir lime. Eventually the conversation turned to pearl farming near on Manihiki (his birthplace) and the current underwater search for rare-earth minerals.

Commenting on the importance of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (which former President Trump dropped and which President George W. Biden has now rejoined), Puna reminisced about hosting Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, whom he described as delightful, intelligent and well informed. But it was the pan-seared mahi mahi with ginger and garlic that finally turned the conversation to global warming and the ocean.

“That former president, Trump, he doesn’t believe in clean energy,” he said, noting that melting ice means rising sea levels, threatening Aitutaki and the Cook Islands’ other atolls. “And yes, we’re worried,” he said, “but we’re doing our part. Right now 50 percent of these islands’ electric power comes from solar installations. In another four years our islands will be 100 percent solar.” Well, I said to myself, if only the rest of the world could say that.

THE NITTY GRITTY:

COOK ISLANDS TOURISM: Hotels and resorts are listed at www.cookislands.travels.

WEATHER: June through September is warm and dry. December through March, the rainy season, is hotter and more humid. Shoulder months – April, May October and November – are variable.

GETTING AROUND: You may not need to rent a car. Most activities, cafes and beaches can be reached by cab or bicycle. For tours or expeditions see outfitters like Tik e-tours (www.tik-etours.com) and Storytellers Eco Cycle Tours www.storytellers.co.ck.

FLIGHTS: Limited flights may make it hard to choose a date. At the present, Air New Zealand operates the only non-stop flight from the U.S. to Rarotonga, a nine-to-ten-hour flight. Choose economy, premium business, and beds. Rates are geared to New Zealand’s holiday seasons.

For more, follow veteran traveler Anne Cooke on Facebook at “Anne Z. Cooke” and on Twitter at @anneontheroad.