PORT LLIGAT, Girona, Spain – What’s old in Girona, in Catalonia, Spain, but as tomorrow as a trip to Mars? Not the ancient ruins at Empuries, nor the coast-hugging Roman road, the Via Augusta, now paved and numbered. Nor is it Girona’s ancient vineyards or the Costa Brava’s sandy shores and emerald coves.

The word is that the Dali Theater-Museum, celebrating the life and work of its enigmatic founder Salvador Dali, (1904-1989), Girona’s world-famous surrealist artist, is now one of the city’s most visited tourist attractions. The revival of interest in his paintings, both revered and ridiculed during his lifetime, are now seen as visionary.

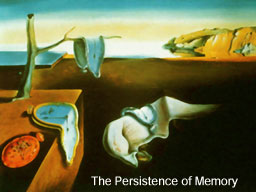

Dali’s most recognized painting, the Persistence of Memory, now in the Museum of Modern Art, in New York, depicts — according to some — a dying world, marked by a scorched landscape and melted pocket watches. Or as one of the guides in the Dali Theater-Museum explained to the tour group I joined, the painting clearly suggests that dream time is elastic, the drooping clocks a clue to its creator’s inner life.

Dali’s most recognized painting, the Persistence of Memory, now in the Museum of Modern Art, in New York, depicts — according to some — a dying world, marked by a scorched landscape and melted pocket watches. Or as one of the guides in the Dali Theater-Museum explained to the tour group I joined, the painting clearly suggests that dream time is elastic, the drooping clocks a clue to its creator’s inner life.

Are his paintings symbolic or are they a joke? asked a frowning young man who’d been standing silently, pondering an image of Dali’s wife titled Galatea of the Spheres. The guide blinked and the query went unanswered. Fortunately for historians, Dali, the man, who spent most of his life in Girona, left as many clues as he did art.

Dali’s life in Girona, his home in Port Lligat and his wife’s home in Pubol, both open for guided tours, offer surprising insights into the artist and the man. Sunny summers in the beach town of Cadaques, 15 minutes from Port Lligat, where his family often summered – and where I spent a charmed afternoon – fostered a love of the sea. For clues to his last decade, and some of his largest most ambitious projects, the answers are found in the Dali Theater-Museum, a building he designed and built on the site of his favorite movie theater, in Figueres, where he grew up.

I should have started at the museum when I headed to Girona for a long-planned, two-week escape. But Salvador Dali was the last thing on my mind. I’d been to the Costa Brava years earlier, stayed a couple of days and spent most of my time there on the world’s most inviting beach. Going back again, I realized Girona was a town with a history. Settled 2000 years ago by the Iberians and officially founded by the Romans in the 5th century, it has been a proud survivor.

Free to wander, I spent a couple of days exploring the Old Quarter, first circling the area on the path of 4th century Roman wall, then visiting various 10th century monasteries and churches. Deep in the middle of the ancient streets I discovered a wide spot, with a couple of shade trees and a café, my lode stone from that moment on.

On the advice of Marco, the hotel clerk, who said he was more interested in movies than history, I climbed the 91 stone steps up to the entrance of the 12th century Romanesque Cathedral, built on top of a mosque, after the Moors were defeated and driven out. They’re the same steps that the “Game of Throne” used when they were filming the last season, he said, beamingly. Counting each step, I thought of the countless people who’d been there before me.

Marco also recommended a sight-seeing bus tour north along the coast to the Cap de Creus, the tip of a rocky peninsula jutting into the Mediterranean Sea. The drive, winding through bush-covered hills ended above a windswept rim, looking down at the water and a chain of small bays. Munching a bag lunch and stretching my legs, I spotted a sailboat leaning into the wind, heading north toward the French border, 16 miles away. Before there was a border, Phoenician and Greek ships came this way, stopping at coastal villages like Empuries, to trade.

Ten days into my vacation, done with museums and the occasional vineyard tour and wine-tasting, I headed to the beach, still the softest sand and freshest water on the Mediterranean’s western shore. Striking up a conversation with a couple of Canadians sunning nearby made the afternoon fly by. They had rented an apartment for six weeks, I was in a hotel; they were going on to Madrid, I was flying back to Denver. We both liked skiing at Whistler Blackcomb, in British Columbia. And they wanted to know more about Salvador Dali.

So, I tagged along, heading first for – Pubol Castle, the 12th century mansion Dali bought in 1970 for his wife Gala. Larger than it appears from the entrance, it consists of a main house, a tower and an open-air covered passageway, surrounded by gardens.

Joining a tour, we were waved through by a guide who offered a brief history: The renovation of the building, Dali’s interior designs and the decade that Gala lived there alone, entertaining overnight guests, both women and men, and banning Dali, except by her written invitation.

People ask why she wanted a house of her own, said the guide, when the rest of the group drifted away to other rooms. Dali was 67 or 68 then, and Gala was 77, ten years older than he was. Too old to want another man, you’d think. He loved her, but they couldn’t live together. Like many couples.

Whatever the reason, Dali rebuilt the structure and surrounded it with gardens, tucking home-made stick-thin elephants between the leaves. Furnishing the rooms with satin and velvet, he installed modern bathrooms and a kitchen, and he decorated with paintings, ceiling murals, wall hangings, hand-decorated tiles, tiny tables, angular arm chairs, mirrors and dozens of little baubles and charms. A reluctant collector myself, it tickled my heart to see that he, too, couldn’t resist objets d’art.

Spotting a lion’s head lying on top of an 18th century wardrobe (a clothes closet), near an out-of-focus photo of a person, I took a second look. Comic theater? Or was Dali spoofing the book, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe? He could have read it when they fled Spain for New York City, in 1940, after the Nazis invaded France.

Before we left, I went to the photography exhibit upstairs to see what Dali and Gala looked like together, in plain black and white. They’re in their Manhattan studio, she’s laughing for the photographer, and he, the celebrity of the moment, is mugging for the photographer, with his trademark wide-eyed stare and curvy black mustache.

The next day we headed for Dali’s permanent home on the shore in Port Lligat, a house filled with gewgaws, cartoon figures, knickknacks, a stuffed bear next to the stairs and chains of tiny, dried, white everlasting flowers. The sort of things a teenager collects.

The house, with several six-foot white eggs mounted on the roof, one of them half-cracked, were a link to his older brother, who died at nine months old. According to Rosia our guide, the cracked egg, big enough for a man to climb inside, symbolized Dali’s other half, without which — it’s said, he always felt incomplete.

I’d already been to the museum in Figueres; now I wished I’d saved it for last. Making another reservation I went again, walking and looking. This time the place was packed, the rooms crowded with guided tours. Don’t come on Saturday if you can avoid it. But if those drooping clocks leave you wondering, come. This is where the pilgrimage ends and disconnected symbols click together, making sense. I hope. At the very least, I left with a new respect for Spain’s greatest 20th century painter.

For more: See Salvador Dali’s Celebrity suites, Part 3 at the Hôtel Maurice in Paris.