“Gold! Gold! Gold! Gold!” headlined the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on July of 1897. “Sixty Eight Rich Men on Steamer Portland arrived in Seattle with ‘Stacks of Yellow Metal.”‘ The news spread like California wildfire, and the Klondike Gold Rush began. In the first ten days over 1,500 people left for the Klondike. Within the next six months, approximately 100,000 gold-seekers steamed up Alaska’s Inside Passage and arrived in Dyea and Skagway, the base for two treacherous overland treks to the Klondike gold fields. Only 30,000 completed the trip, 4,000 or so found gold, and barely a few hundred struck it rich.

The ones who did make a fortune were the merchants and profiteers who took advantage of the inexperienced miners, who they referred to as ‘stampeders.’ Long before the days of mass media, most of the ‘get-rich-quick’ miners knew virtually nothing about where they were going and the hardships that lay ahead of them. Pamphlets and newspapers contained little or no real information, but made outrageous claims of wealth, with riverbeds of gold just sitting there for the taking. Seattle served as water route and the gateway to the Yukon. Advertised as the ‘outfitter of the gold fields,’ merchants sold supplies, stocked ten feet high on storefront boardwalks

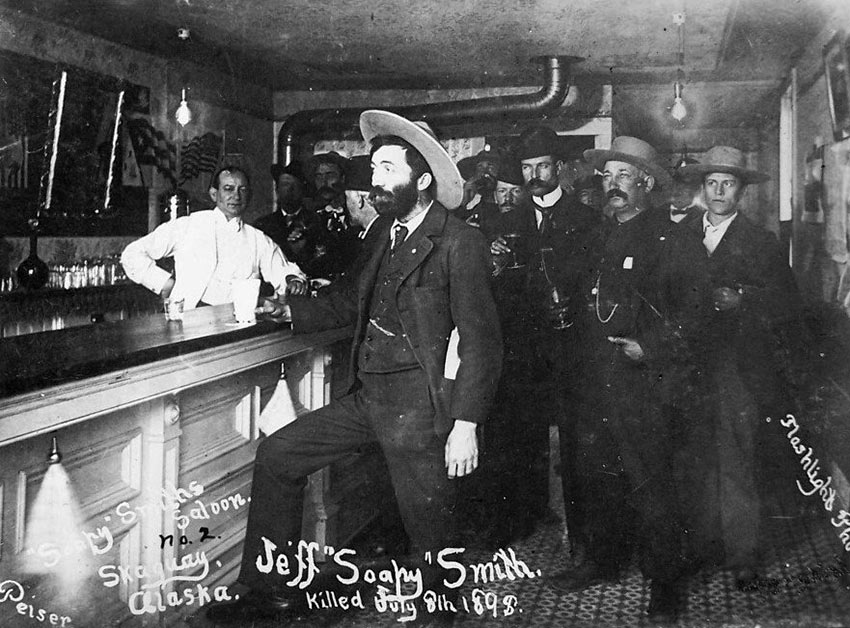

Driven by dreams of unfathomable riches, the first stampeders arrived in Skagway and found themselves confronted by an inhospitable muddy settlement that was barely a collection of tents. They were also met by a swarm of con men, whose only interest was taking their money. The most infamous of the swindlers was ‘Soapy’ Smith and his gang of “bunco men.” One of their schemes was operating a telegraph office, where an important message could be sent to cherished friends and family anywhere in the world for $5, which was a lot of dough in 1897. What the stampeders didn’t know was that there were no telegraph wires to or from Skagway.

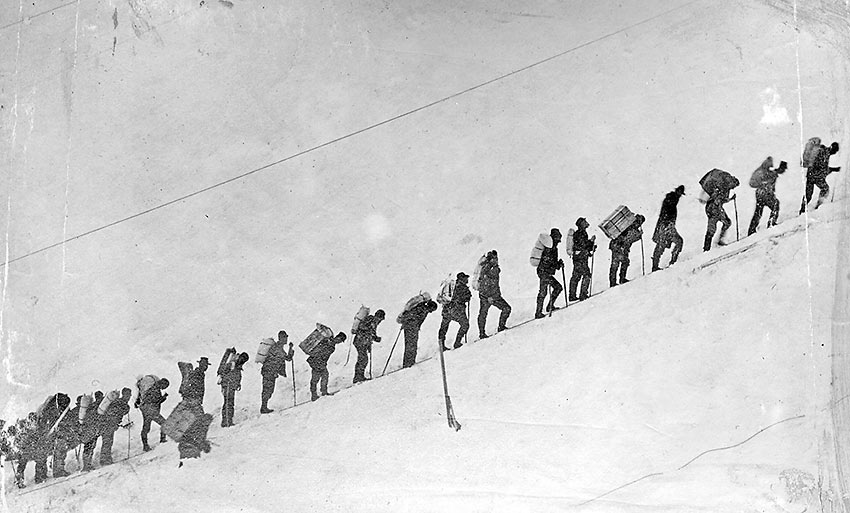

The stampeders also faced a choice of two horrendous trails which had to be climbed before the freeze-up, then another 550 mile journey through the lake systems to the Yukon River’s gold fields. The North West Mounted Police had created the “One Ton Law of 1898,” requiring all miners entering Canada to carry a year’s supply of food and equipment, equaling around 2,000 pounds. The 45-mile long White Pass Trail was promoted as a horse-packing trail and appeared easier than the Chilkoot Pass, where the miners had to carry supplies on their backs. The trail turned out to be even more difficult because of muddy bogs, massive boulders and steep rocky cliffs. Over 3,000 horses died along the way, and it was quickly dubbed the “Dead Horse Trail.” It was obvious that there was need for a better form of transportation up the White Pass Trail.

In 1897, three separate companies organized to build a railway from Skagway to Fort Selkirk, Yukon, 325 miles away. The project ran into some roadblocks due to corrupt local city officials and Soapy Smith. This ended when Smith was killed in a gunfight, and the White Pass & Yukon Route railway – “the railway built of gold”– began construction. Considered almost an impossible task, tens of thousands of men were challenged by a godless climate and brutal geography. Twenty-six months later, construction reached the 2,885-foot summit of White Pass, 20 miles away from Skagway. On July 6, 1899, the last spike was driven in Bennett, British Columbia.

With numerous cruise ships stopping at Skagway, a re-creation journey on the White Pass & Yukon Route sounded like a perfect fit. The rails were laid right down to the docks, ideally positioned to sell a railroad ride through the mountains to the tourists. Billed as the “Scenic Railway of the World,” the White Pass & Yukon Route reopened between Skagway and White Pass in 1988. The White Pass & Yukon Route railway allowed tourists an opportunity to step back in time and experience some of the grueling details of Klondike Gold Rush for themselves. Still using vintage parlor cars – three with wheelchair lifts – the WP&YR runs on its original narrow-gauge track, rising from sea level at Skagway to 2,885′ at the White Pass summit in only 21 miles. Forget Disneyland. This is the real deal. With steep grades up to 3.9% and cliff-hanging turns of 16 degrees, the railroad seemingly hangs on the mountainside for most of the way to the summit. A series of wooden trestles skirt the landscape. A spectacular steel cantilever arches 215 feet above Dead Horse Gulch, once the highest railroad bridge in the world.

It’s a breathtaking piece of country with a stunning panorama of mountains, gorges, waterfalls, tunnels and historic sites. Period clad railroad men offer a folksy narration. A wood-burning stove keeps everyone warm. Today the White Pass & Yukon Route is Alaska’s most popular shore excursion, and is an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, a designation shared with the Eiffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty and Panama Canal.

Click here for information about the White Pass & Yukon Route

Jay Jamison

January 4, 2018 at 6:55 pm

This brings back great memories of our trip there four years ago. And I remember Ed, you gave us some pointers that helped us navigate our adventure. Nice photos Deb.

Thanks Ed.