Directed by Mamoru Oshii

Directed by Mamoru Oshii

Writing Credits: Shirow Masamune (based on the manga by) (as Masamune Shirow)

Screenplay: Kazunori Itô

Music: Kenji Kawai

Cinematography: Hisao Shirai

Film Editing: Shûichi Kakesu

Production Design: Takashi Watabe

Art Direction: Hiromasa Ogura

Art Department: Makiko Kojima (ink and paint)

Special Effects: Mutsu Murakami

Cast: Atsuko Tanaka, Iemasa Kayumi, Akio Ôtsuka

Ghost in the Shell (GitS) 1995

Walt Mundkowsky

(Mostly written 1996-1997)

Mamoru Oshii’s feature-length Ghost in the Shell beckons for relevance: Original title was Kôkaku Kidôtai (Man-Machine Interface) — my own computer battleground in the past two weeks!

The anime thriller Ghost in the Shell (1995) scarcely needs my advocacy, having sold more than 200,000 copies in the U.S. since last summer. Still, I’m not convinced that everyone who could be receptive knows about it. This tale of a resolute cyborg heroine represents a solid advance over previous genre examples, both in its execution and thoughtful dilemmas.

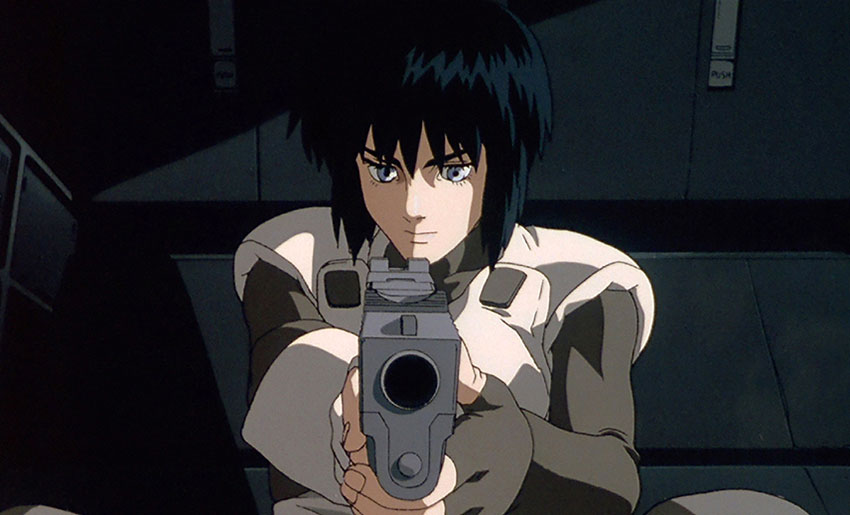

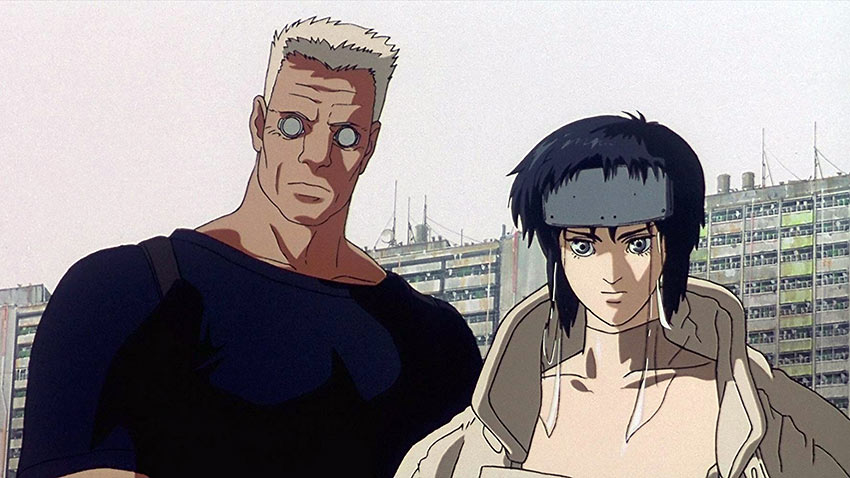

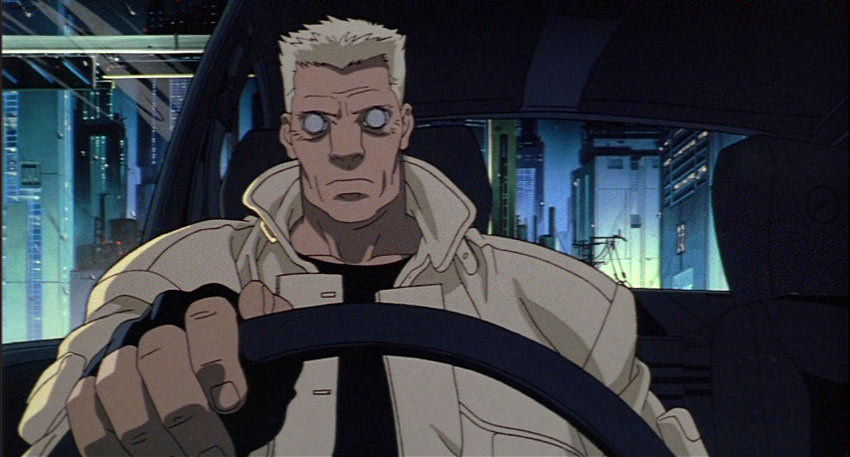

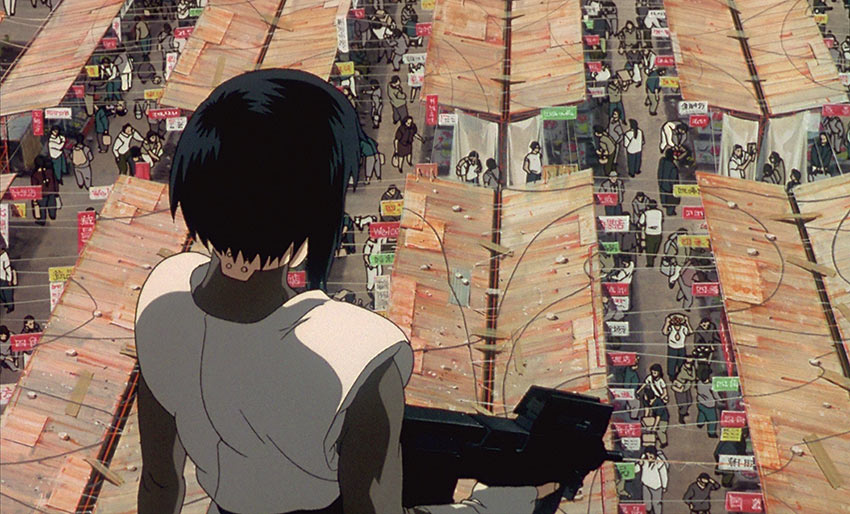

“Major” Motoko Kusanagi is a top cop at Section 9 (State Security). In addition to superhuman physical prowess, she can tap into any computer network via a quartet of terminals in her neck. For all this augmentation, her titanium shell, or skull, retains her original “ghost” — the locus of memory and intuition that provides human individuality. With her squadmates Bateau (a much-altered veteran) and Togusa (a recent transfer from the regular police), Motoko is investigating a lengendary hacker called the Puppet Master. (He manipulates unsuspecting citizens by planting false information in their ghosts.) As the complex plot spirals into overdrive, the Puppet Master is seen trying to break away from his master, the scheming Ministry of Foreign Affairs. While Motoko prepares to “dive” into his program, she is the object of the Puppet Master’s own search.

Unflinching in action, Motoko is beset by private qualms about her identity. “When I float weightless back to the surface,” she tells Bateau of her passion for scuba diving, “I imagine I’m becoming someone else.” Her tough interrogation of one of the Puppet Master’s ghost-hacked minions (“Don’t you have any happy childhood memories? Don’t you even know who you are?”) eventually turns into self-doubt. The Puppet Master himself, “a living, thinking entity who was created in the sea of information,” has meanwhile generated his own ghost. He applies to Section 9 for political asylum, even though he has no permanent body.

Just as sophisticated is the attitude toward technology; the usual either / or extremes — blind acceptance and paranoia — are surpassed in a single leap. Early on Motoko explains to Togusa how vital his human presence is to the unit’s success, that if all parts of the whole react in the same way, “you breed in weakness.” The Puppet Master elaborates this theme, stating that mere copies cannot perpetuate his line because “copies do not give rise to variety and originality.” His desire to merge with Motoko is coldly conceptual on its face, but it speaks the language of love: “We will both undergo change, but there is nothing for either of us to lose.” (She isn’t convinced.) Here the movie eases onto the rim of the mystical, opening new areas for examination.

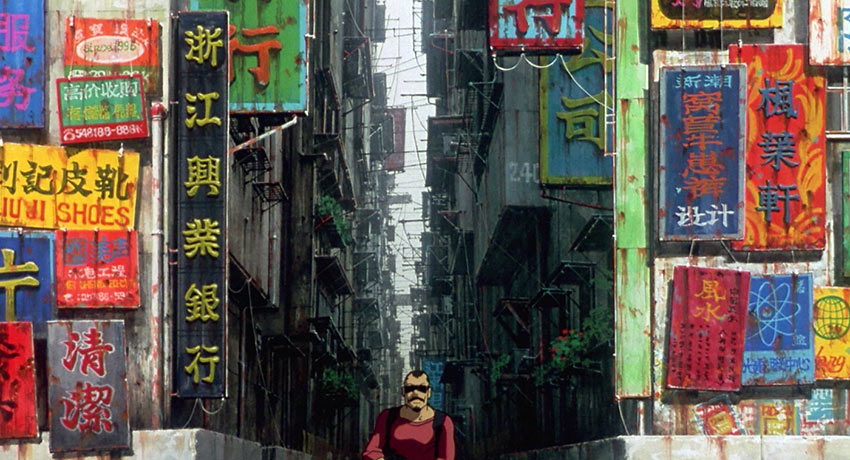

It’s easy to lose oneself in the detailed, energetic drawing and cohesive blue-centered color scheme. (The lovingly rendered reflections in puddles should enchant Ridley Scott.) Smashing combat scenes aren’t unexpected, given director Mamoru Oshii’s past work (Patlabor 1 and 2). I’d rather point to the freshly conceived casual gestures — Motoko flicking the sleep from her eyes and struggling into her jacket, clamping on her body armor while talking, or sweeping back her wet hair as she emerges from a sea dive. Oshii’s dynamic framing and crisp cutting vanquish anime’s frequent flatness of image. The shots of Motoko’s chopper among the ice-blue skyscrapers at night constitute the closest brush with Blade Runner, but emotional gravity is much more specifically tied to character here.

The rejection of routine extends to Kenji Kawai’s music, which left some unhappy. It underlines Kusanagi’s fragility more than it celebrates her skills, but the film’s legion of admirers should have the CD, for when they want to isolate the plaintive, trance-like sounds from the pictures.

Kawai’s melancholy textures could seem wrong — a static procession of drum strokes, bells, chimes and synth effects, but in fact the transparent scoring never clogs the combat and assists the contemplative side immeasurably. (The opening montage of Motoko’s cyborg body being made gets an ancient Japanese marriage ceremonial as soundtrack.) CD tracks follow the order on film, keeping the most riveting stuff together — “Nightstalker” (a biwa melody over synth strings) is the Major’s poignant chopper ride, ending at “Floating Museum” for the climactic battle. A soaring solo vocal covers her heroism. Top-drawer sound for the time (each note emerging from silence) matters.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Bernard

December 18, 2018 at 1:00 pm

Finally! A great review of a classic Japanese anime. Well done!

I love this genre. Unlike America, Japan treats their animations with adult sophistication. Ghost in a Shell was ahead of its time so it’s not surprising that the American production team that made the live action movie with Scarlett Johanson just didn’t get it.

I want more of this.