As I stood in downtown Tulsa, Oklahoma I was amazed by the lushness of its greenery and sense of cosmopolitism. This was my first trip to Oklahoma, and in my naiveté, I had thought the whole state was one big Dust Bowl. Perhaps I had seen John Ford’s film adaption of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath too many times, but that image had been branded in my mind. As the late afternoon sun lowered, showering the cityscape in a stunning Oklahoma Technicolor sunset, my preconceived notions had just ended. I couldn’t wait to explore this culturally vibrant, yet unfamiliar city.

Tulsa and Its Area

In a region known as Green Country, Tulsa rests on the Arkansas River, between the Osage Hills and the foothills of the Ozark Mountains in northeast Oklahoma. It was first settled in 1828 by the Lochapoka Band of the Creek Nation during the disturbing period of the Indian Removal Act. The city boomed during the 20th century as an important center for the U.S oil industry, making Tulsa County the most densely populated area in Oklahoma. Today Tulsa is the cultural and arts center of Oklahoma, showcasing ballet and opera companies, grandiose 20th Century churches and one of the nation’s largest concentrations of art deco architecture. Its collection of world-class museums include the Gilcrease Museum of Art and the Philbrook Museum of Art (now in two locations).

The Woody Guthrie Center

The Woody Guthrie Center is an inspiring tribute to the man best known for composing the song This Land Is Your Land, as well as championing social equality to all Americans through music. Woodrow Wilson Guthrie (born July 14, 1912, Okemah, Oklahoma) chronicled the plight of common people, especially during the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl era. Like other displaced people from Oklahoma’s Dust Bowl, he headed for California, traveling by freight train, hitchhiking or simply walking westward. He supported himself by singing and playing in taverns, taking odd jobs, and visiting hobo camps – giving him an unflinching education of a world where the rich had everything and the poor, seemingly nothing. In Los Angeles he landed a job at radio station where his songs gave voice to the struggles of the dispossessed and downtrodden, while still celebrating their indomitable spirit. His activist music later had a tremendous influence on everyone from Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, to Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Phil Ochs. Some of the most lasting songs in the canon of American music include Guthrie’s So Long (It’s Been Good to Know Yuh), Hard Traveling, Blowing Down This Old Dusty Road, Union Maid and, inspired by John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, the song Tom Joad. This Land Is Your Land* became a pillar of the civil rights movement of the 1960s and gets my vote for a new U.S. National Anthem.

The Cherokee Nation and The Trail of Tears

Located in Tahlequah, just outside of Tulsa, is the home of the Cherokee Nation. Their story is an inspiring profile in courage as they overcame egregious acts of illegality and brutality by the U.S. government. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson pushed a new piece of legislation through Congress called the Indian Removal Act. American-Indian tribes** were to give up their lands east of the Mississippi River in exchange for lands to the west in the Oklahoma Territory. A number of American-Indian Nations made attempts at non-violent resistance, but eventually felt that the removal was inevitable, with no way to stop the U.S. Government. The 22,000 members of the Cherokee Nation, based primarily in northern Georgia, refused to relocate. The Cherokee decided to take their protest all the way to the Supreme Court. Considered one of the “civilized” tribes of the Southeast, the Cherokee had adopted Euro-American practices of large-scale farming, western dress and education, and the white tradition of slave-holding. They even had an English language newspaper. Supreme Court Justice John Marshall sided with the Cherokee, saying that they had a constitutional right to stay in their ancestral homeland.

“Marshall has made his decision, now let’s see him enforce it!” – President Andrew Jackson

In 1838, the U.S. Government sent in 7,000 troops, who forced the Cherokees into stockades at bayonet point. They were not allowed time to gather their belongings, and, as they departed, their homes were looted by new white settlers before their very eyes.

“I fought through the War Between the States and have seen many men shot, but the Cherokee removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.” – Matthew Edward Lear, Georgia soldier who participated in the removal of the Cherokee.

The Cherokee began a thousand miles march to an area in present-day Oklahoma, just outside of Tulsa. Over 4,000 out of 16,000 Cherokee people died of cold, hunger, exhaustion and disease, primarily seniors and infants. The Cherokee people call this journey “The Trail Where They Cried” (Anglicized “The Trail of Tears“) – a journey that saw more people die than perished in the attacks of September 11, 2001.

In the years that followed, the Cherokee struggled to reassert themselves in this new, unfamiliar land in the Oklahoma Territory. Soon they transformed the area, creating a progressive court and education system with a literacy rate higher than the rest of the U.S. Many white settlers took advantage of their superior schools, and paid tuition to have their children attend the Cherokee schools. Today the Cherokee Nation is the second largest American-Indian Nation in the United States. They are an all-inclusive tribe where one can have 1/32nd Cherokee blood and still be considered a full member of the nation. Yes, that’s right, think: Elizabeth Warren. There are currently more than 290,000 tribal members; 70,000 of them reside in the 7,000 square miles of the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma. The state grew up around the nations of the American-Indian Territory, and that influence can be seen today.

A trip to the Cherokee Village features replicas of traditional homes from the time of intense cultural transformation. Guides and villagers demonstrate traditional Cherokee crafts such as basketry, pottery, flint knapping, blow guns and field games, where disputes were handled by playing the field games, with the loser accepting the results.

The Cherokee National Museum offers exhibits, cultural workshops and events. The center includes the Adams Corner Rural Village, Cherokee Family Research Center and Cherokee National Archives. The museum houses the award-winning Trail of Tears interpretive exhibition – an experience that will stir you to the depths of your soul.

The Cherokee National Supreme Court Museum is the oldest government building in the state of Oklahoma. The Supreme and District courts both hold sessions here. Historical items include photos, stories, objects and furniture. The building also houses the printing press of the bilingual Cherokee Phoenix – the first bilingual newspaper in the U.S. – and the Cherokee Advocate.

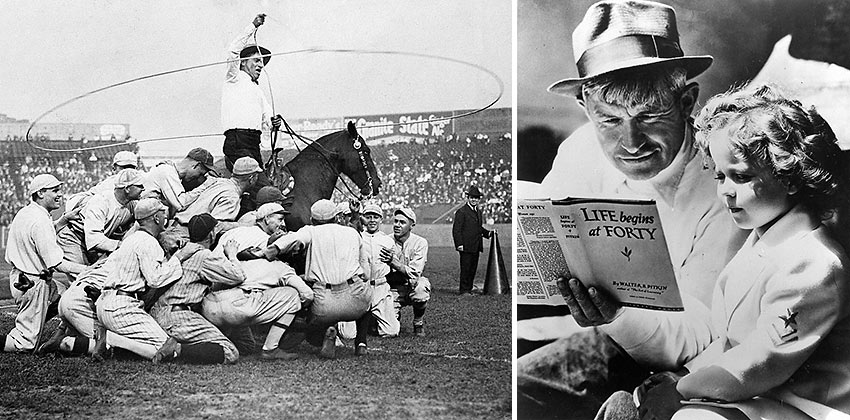

Will Rogers Memorial Museum

Many images come to mind at the mention of William Penn Adair “Will” Rogers: a rope twirling Cherokee-American cowboy, radio personality, humorist, newspaper columnist, social commentator, vaudeville performer and actor who starred in 71 movies. Also referred to as Oklahoma’s favorite son, Rogers was born to a prominent Indian Territory family in 1879. His father was a Cherokee senator and a judge who helped write the Oklahoma Constitution.

The Will Rogers Memorial Museum, just a stone’s throw away from Tahlequah in Claremore, memorializes him with artifacts, photographs, films and manuscripts pertaining to his remarkable life. I particularly enjoyed a section of the spacious museum, dedicated to his quotations. My favorite: Everybody is ignorant, only on different subjects. Rogers’ tomb is located on the museum’s 20-acre grounds overlooking Claremore.

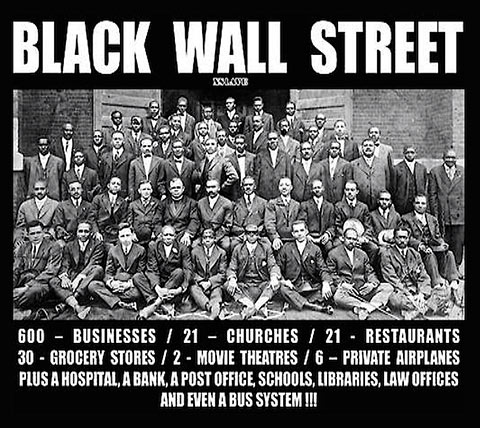

Greenwood Cultural Center and the Tulsa Race Riot

The small Greenwood Cultural Center houses one of the most bleak and secretive tragedies in U.S. history: The Tulsa Race Riot. The Greenwood District was an affluent African-American community, nationally known as the Black Wall Street. During the Jim Crow era of the 1920s, most of Tulsa’s 10,000 black residents lived in that neighborhood, which included a thriving business district, expensive homes, nationally-known doctors, lawyers, bankers, business owners and millionaires.

Due to segregation, it was almost like a self-contained city, where citizens conducted all their business – shopping, attending theaters and dining in restaurants in the 300 black-owned businesses of Greenwood – which added to the district’s affluence. Due to a still dubious claim by a white female elevator operator that a black 19-year-old shoe shiner, Dick Rowland, did something to offend her in the elevator, Rowland was immediately arrested and sent to jail. Rumors of what had supposedly happened began to circulate through the city’s white community. That afternoon a front-page story in the Tulsa Tribune enraged the white populace with the report that the police had arrested a Negro man for sexually assaulting a white woman.

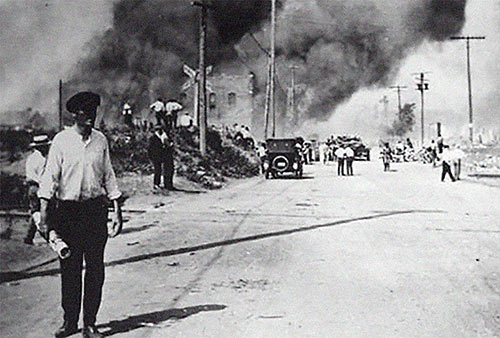

When a white mob gathered at the jail, Rowland was moved from the city jail to the more secure county lockup on the top floor of the courthouse. Growing numbers of the white mob, now estimated at 2,000, marched to the courthouse, demanding Rowland to be lynched. When the mob attempted to storm the building, Sheriff Willard McCullough and his deputies heroically dispersed the crowd, protecting Dick Rowland from death. Later that night, there was a struggle between an African-American man with a gun, who had arrived at the courthouse to protect Rowland, and a white protester. As they wrestled for the gun, it accidentally went off, killing the white man. This incensed the mob to a boiling point. As one man observed, All hell is about to break loose!

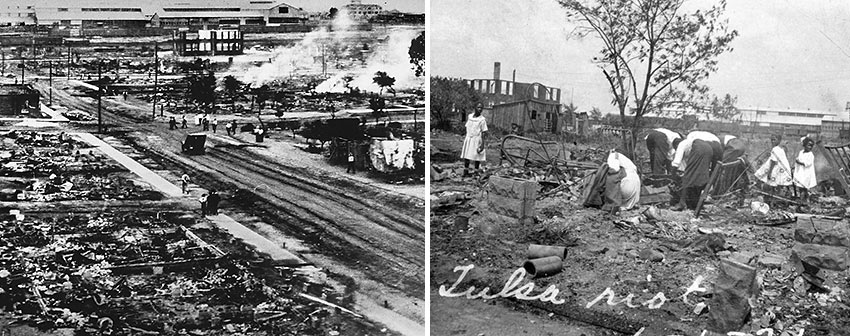

In the following early morning hours of June 1, 1921, vigilante mobs of white rioters poured into Greenwood; killing, looting and burning all 35-blocks to the ground. The city government of Tulsa conspired with the mob, arresting more than 6,000 black residents and refusing to provide them with protection or assistance. Law enforcement officials used airplanes to drop firebombs on buildings, homes and fleeing families; stating they were protecting the city against a “Negro uprising.” Over 6,000 African-Americans were imprisoned, and historians believe as many as 300 African-Americans were killed, while thousands were left homeless. News reports were largely squelched. You will hardly find any mention of the worst U.S. incident of racial violence in any national public school history books, Oklahoma classrooms or even in private conversations. I was surprised that my guide (an informative and pleasant young man) knew nothing of the massacre and I had to direct him to the site. In April 2002, a private religious charity, the Tulsa Metropolitan Ministry, paid a total of $28,000 to the known survivors, a little more than $200 each, using funds raised from private donations.

The Tulsa Race Riot remains the worst incident of racial violence in U.S. history. Thankfully, the Greenwood Cultural Center keeps this story alive today. Their mission is to preserve African-American heritage and promote positive images of the African-American community by providing educational and cultural experiences promoting intercultural exchange, and encouraging cultural tourism.

Epilogue: Olivia Hooker: Tulsa Race Riot Survivor Dies Aged 103

Courtesy www.bbc.com/news/world/us_and_canada

When Olivia Hooker was six years old, she was forced to hide under a table as a white mob destroyed the neighborhood around her. Later, she would recount how she struggled to stay silent as the torch-carrying men took an axe to the family piano. Outside, as many as 1,000 homes and businesses – including her father’s clothes store – were being reduced to rubble.

The 1921 Tulsa race riot, as it would become known, would also leave as many as 300 black people dead. But the horrifying incident in Oklahoma would be far from the only distinguishing moment of Ms Hooker’s remarkable life.

In her 103 years, she would become the first African-American woman to join the US Coast Guard, go on to gain a PhD and eventually play a key role in getting some justice for the victims of the race riots, more than 70 years after the fact. She would be praised as a “tireless voice for justice and equality” by America’s first black president, and called “a national treasure” by the head of the US Coast Guard.

Read her full story here

There was still much to do and see in Tulsa, a city that receives very little national coverage, and I will return again. Plus, I still didn’t get my fill of the Texas-Oklahoma specialty: Chicken-fried steak. Next trip to Oklahoma, though, I’ll also include an exploration of Oklahoma City to learn more about the Dust Bowl; take a guided tour of the Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum that covers the April 19, 1995 bombing of Oklahoma City’s Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building; and a visit to the Western Heritage Museum.

Editor’s notes:

*The Star Spangled Banner was made the U.S. National Anthem by a congressional resolution on March 3, 1931. During the period between the first World War and 1930, the unofficial U.S. National Anthem was Over There, a 1917 song written by George M. Cohan. The lyrics for the Star Spangled Banner are based on an 1814 poem by amateur poet Francis Scott Key, entitled Defence of Fort McHenry. Key penned the poem after witnessing the bombardment of Fort McHenry by British ships during the Battle of Baltimore in the War of 1812. The music that accompanies the lyrics was first known as The Anacreontic Song, written by the Englishman John Stafford Smith for an English gentleman’s club. It soon became a popular on both sides of the Atlantic as a drinking song that glorifies drink and women. The music was added to Key’s poem, with the title of the song changed to the Star Spangled Banner. The problem: when The Founding Fathers established the new U.S. Republic, they went to great lengths to distant themselves from all things English. This included the construction of neo-classic Greek and Roman government buildings, as opposed to English Gothic, which was the rage of that period. Thomas Jefferson felt that ancient Greece and Rome expressed the ideals of democracy, and both state and federal government buildings throughout our new land adopted this type of architecture. Some banks and churches in the big cities also followed suit. I believe The Founding Fathers would find it disturbing that the music to the Star Spangled Banner was written by an Englishman, as opposed to an American.

** I have traveled to many Tribal nations throughout the U.S., and was informed by numerous Tribal Elders that their people prefer to be called by their Tribal names, or generically American-Indian, for that was how the treaties were signed with the U.S. Government, despite many of them broken by the U.S. The term Native-American is a name coined by politically correct Anglo-Americans. This makes no sense to me. For example, I was born in Seattle; therefore I am a Native-American, too.

Peggy Polinsky

November 29, 2018 at 3:41 pm

Hi Ed – I would like to buy the Traveling Boy book, but I boycott Amazon (the taking-over-the-world company). Is there any other way I can get a copy?

Thanks, Peggy

Peggy Polinsky

November 29, 2018 at 3:42 pm

By the way – what an interesting piece about Tusla!! Who knew? Not me. Now I do – wonderful!

Thanks, Peggy