By Walt Mundkowsky

By Walt Mundkowsky

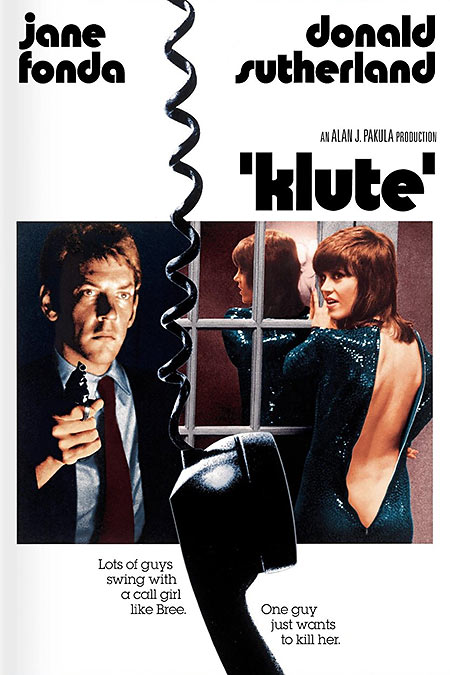

Directed by: Alan J. Pakula

Writing Credits: Andy Lewis and David E. Lewis

Cinematography: Gordon Willis

Cast: Jane Fonda (Oscar winning performance), Donald Sutherland, Roy Scheider, Charles Cioffi

Alan J. Pakula’s Klute (Warner Bros.) represents a considerable advance over the first film he directed, but what wouldn’t? The Sterile Cuckoo was an abomination, from the clunky camera set-ups and music to Liza Minnelli’s uncontrolled performance, all emotion and no design. Throughout I was struck by the chasm between what the picture thought it was presenting (a love-starved, skittish adolescent) and what I saw (a deranged girl crying for love and killing it off in one motion). Like its predecessor, Klute has been greeted with extravagant praise; Pauline Kael’s paean led me to expect a film half “full-scale, definitive portrait of a call girl” and half “powerful, scary melodrama,” which sounds rather like constructing a novel by alternating chapters from Zola’s Nana and Psycho. At any rate, no such luck: The thriller half does not compare with Dario Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, from which it appears largely derived; the call-girl half is mostly shallow and sketchy.

The screenplay by Andy and Dave Lewis fails to fuse the two halves for any length of time; they keep breaking apart and jostling each other. The thriller half contains the plot. John Klute is a small-town policeman who comes to New York to investigate the disappearance of a friend. The missing man seems connected with a call girl named Bree Daniels — he wrote her some obscene letters — but she doesn’t remember him. (A New York detective says of her, “A good call girl — she’ll turn six or seven hundred tricks a year. Faces get blurred.”) Klute starts with her and they pursue the slimmest possibilities — an ex-roommate of Bree’s and junkie who could be anywhere, and a phantom-like maniac who likes to beat up women. Bree begins to fall in love, somewhat unwillingly, with Klute. Unsurprisingly, the investigation comes full circle: The maniac is the man who sent Klute to New York in the first place. Bree and Klute leave together, though she’s iffy about their future.

The screenplay by Andy and Dave Lewis fails to fuse the two halves for any length of time; they keep breaking apart and jostling each other. The thriller half contains the plot. John Klute is a small-town policeman who comes to New York to investigate the disappearance of a friend. The missing man seems connected with a call girl named Bree Daniels — he wrote her some obscene letters — but she doesn’t remember him. (A New York detective says of her, “A good call girl — she’ll turn six or seven hundred tricks a year. Faces get blurred.”) Klute starts with her and they pursue the slimmest possibilities — an ex-roommate of Bree’s and junkie who could be anywhere, and a phantom-like maniac who likes to beat up women. Bree begins to fall in love, somewhat unwillingly, with Klute. Unsurprisingly, the investigation comes full circle: The maniac is the man who sent Klute to New York in the first place. Bree and Klute leave together, though she’s iffy about their future.

I can’t think of anything in this part of the movie that does not misfire. Plot mechanics — threatening phone calls, killer following and attacking lone girls — invite comparison with The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, and Michael Small’s music is a blatant rehash of the wonders Ennio Morricone worked for that film. Morricone’s thriller scores are stamped with catchy tunes of economy and simplicity; grating, incisive, tense harmonies; “sweet-and-sour, now jaunty or jeering, now sensual and insinuating,” as John Simon wrote. Small provides none of this, and proves what I’ve never doubted — if you want a Morricone score, go to the source.

I can’t think of anything in this part of the movie that does not misfire. Plot mechanics — threatening phone calls, killer following and attacking lone girls — invite comparison with The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, and Michael Small’s music is a blatant rehash of the wonders Ennio Morricone worked for that film. Morricone’s thriller scores are stamped with catchy tunes of economy and simplicity; grating, incisive, tense harmonies; “sweet-and-sour, now jaunty or jeering, now sensual and insinuating,” as John Simon wrote. Small provides none of this, and proves what I’ve never doubted — if you want a Morricone score, go to the source.

Klute plods, the one thing a thriller, even a semi-thriller, must not do. Pakula’s sense of where his camera should be has improved only slightly; he has some ease but no real fluency. The camera movements — down the dinner table at the film’s start; retreating as Bree sits up in bed, paralyzed by the ringing telephone or as she slowly undresses for an old client; panning down the face of a skyscraper; through the empty factory where Bree is trapped — are pro forma. Compositions for the Panavision screen are careful, studied and for all that, unimaginative. Besides Argento’s deftness, which lends him an articulate and subtle visual style, he believes in the horror conventions he applies — the pale, lean erotic / murderous witch in her wide-brimmed hat and shiny leather coat. The mystery part of Klute lacks urgency mainly because Pakula has no conviction in what he is doing. He doesn’t seem to buy it for a moment, so neither should we.

The call-girl sections are better, as they benefit from Jane Fonda’s remarkable portrayal. To Time it is “her best performance to date,” and Kael says, “There isn’t another young dramatic actress in American films who can touch her.” (Uh, okay.) I would not call it great. Ms. Fonda immerses herself in the role and brings to it bite and smarts. She makes the most of what contradictions she can find, and that is all. The contrast in Bree’s two sides is perfectly realized: With her clients she is assured, openly provocative, wholly in command (“We could have a good time for fifty. Or if you wanted something extra, it would be a little bit more”); alone in her cluttered flat she looks fragile, hurt, lost. She is trying to get out of “the life” and into modeling and acting — with no success in the episodes we see. She is going to a psychiatrist. The confusions of her life are dramatized in the opening minutes; Carl Lerner’s editing is snappy and telling. But things go wrong.

The call-girl sections are better, as they benefit from Jane Fonda’s remarkable portrayal. To Time it is “her best performance to date,” and Kael says, “There isn’t another young dramatic actress in American films who can touch her.” (Uh, okay.) I would not call it great. Ms. Fonda immerses herself in the role and brings to it bite and smarts. She makes the most of what contradictions she can find, and that is all. The contrast in Bree’s two sides is perfectly realized: With her clients she is assured, openly provocative, wholly in command (“We could have a good time for fifty. Or if you wanted something extra, it would be a little bit more”); alone in her cluttered flat she looks fragile, hurt, lost. She is trying to get out of “the life” and into modeling and acting — with no success in the episodes we see. She is going to a psychiatrist. The confusions of her life are dramatized in the opening minutes; Carl Lerner’s editing is snappy and telling. But things go wrong.

The subsequent attraction to Klute and the affair that follows are ambiguous rather than complex. The script would have us believe that Klute wants to make an honest woman out of her, and that she is drawn to his decency and concern for her future. A standard Hollywood motive is just as plausible: The girl falls for the guy who first ignores her. Early on she remarks with some amusement, “Men have paid two hundred dollars for me and here you are turning down a freebie.” The tensions Bree feels between viewing Klute as an escape from her crushing present, and seeing him as a painful involvement that must be destroyed are achingly captured. After she finally seduces him, she says, “Don’t feel bad about losing your virtue. I sort of knew you would — everybody always does,” and bounds out the door. Her jauntiness is too forced to convince. Sometime later, in bed with Klute again, she asks, “You’re not gonna get hung up on me, are you?” The thriller plot keeps getting in the way of all this, and the resolution defeats any more genuine impulses.

As any kind of clinical study of a call girl, Klute is hopeless. It has no awareness of ritual relationships with pimps and clients. “Pimps don’t get dates for you, they just take your money,” Bree says, and that is all the film has to offer about them. We know nothing of Bree’s background, of how and why she became a call girl. Here again, the thriller material works against an understanding of character.

The scenes with Bree and her analyst form the core of the film; for me, they most clearly illustrate its failure and desire to have things both ways. They are not badly written and Ms. Fonda is superb in them, but they externalize conflicts that should be, and to some extent are, present elsewhere. It would hardly be more obvious if the psychiatrist wore a DEVICE sign around her neck. She intrudes so rarely that Bree’s impact is similar to those times in Godard when a character (Léaud all too often) faces the camera and spouts away. Such scenes can be effective in two modes: Keep the camera on the patient throughout and have the questions issue from offscreen, as Truffaut did in The 400 Blows; or make the questioner substantial in his own right. In The Pumpkin Eater Eric Porter was allowed to act a human being with a set of responses: He got annoyed, bored, interested; he even went on vacation. Klute takes an approach somewhere between the two — cutting is lazy shot / reverse shot ping pong. The analyst hasn’t the status of a recognizable person, yet the emphasis on Bree is diluted. We get neither an intense subjectivity nor a finely delineated objectivity. It’s the problem with the whole film in little.

Pakula’s successes are with his actors. Klute is a thankless, monotone part. Donald Sutherland supplies some dimension by playing him as a methodical, faithful, humorless clod. Supporting parts are solidly cast and acted, but I must point out two women: Betty Murray has a distraught and nervous loveliness in her fleeting appearances as the missing man’s wife, and Dorothy Tristan, splendid in the otherwise dismissable End of the Road, makes a shattering impression as the junkie without once resorting to the battery of actorish mannerisms one usually finds in the role.

I used to think the thriller form could be adapted to all sorts of uses, but I grow less and less sure of that. As for Pakula: He has tact and undeniable ability at handling actors. Today neither of those is a common gift, and he may make a consistently fine film.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.