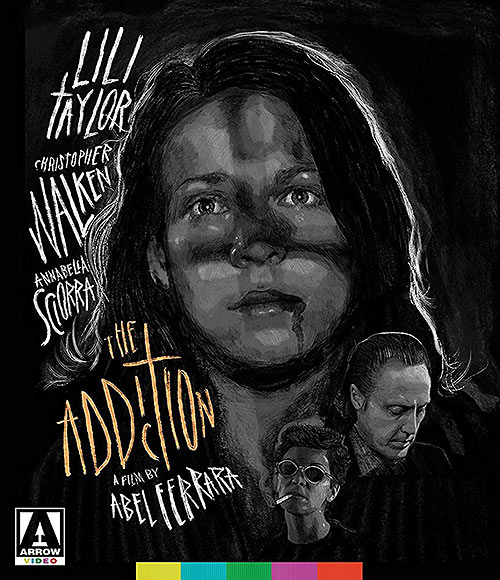

Directed by: Abel Ferrara

Directed by: Abel Ferrara

Writing Credits: Nicholas St. John

Cinematography by: Ken Kelsch

Music by: Joe Delia

Cast: Lili Taylor, Christopher Walken, Annabella Sciorra, Edie Falco, Michael Imperioli

Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction – A Look Back

By Walt Mundkowsky

The Addiction (1995) is the most stringent product of director Abel Ferrara’s current manner — a highly original morality play about guilt and redemption.

Kathleen Conklin is a Ph.D. candidate at NYU’s school of philosophy. One night she is accosted by a sleek female vampire and hurled down a flight of stairs. “Look at me and tell me to go away,” her attacker taunts. “Don’t ask … tell me.” When her assault is completed, she calls Kathleen her collaborator. After periods of shocking illness, Kathleen takes to the vampire trade, at first extracting her victims’ blood with a syringe. (To her the blood is insignificant — “It’s the violence of my will against theirs.”) As her hunger grows, no one she meets is safe. Eventually she encounters Peina, a veteran vampire who has his habit under control. His grand contempt and self-amused pronouncements are a crucial stop along Kathleen’s path to enlightenment. “Please help me,” she begs. “I’m not that person, believe me,” he purrs, turning her out.

Ferrara and his customary screenwriter Nicholas St. John haven’t much interest in the vampire myth — there’s plenty of blood, but nary a fang in sight. Vampirism stands in for the addiction to absolutes, and to disaster itself. Once she has been infected, Kathleen taps an order of experience that mocks both the philosophers she studies and her victims. In the library (no longer the repository of civilized values) she thinks, “This is a graveyard — rows of crumbling tombstones, vicious libelous epitaphs.” Where her bravado cracks, one glimpses a soul in mourning. She covers the mirrors in her flat because (a nice twist of the knife) her crushing guilt makes her own image unbearable. The obligatory vampire orgy leaves her not triumphant but ready for death (or rebirth), sickened by so much blood.

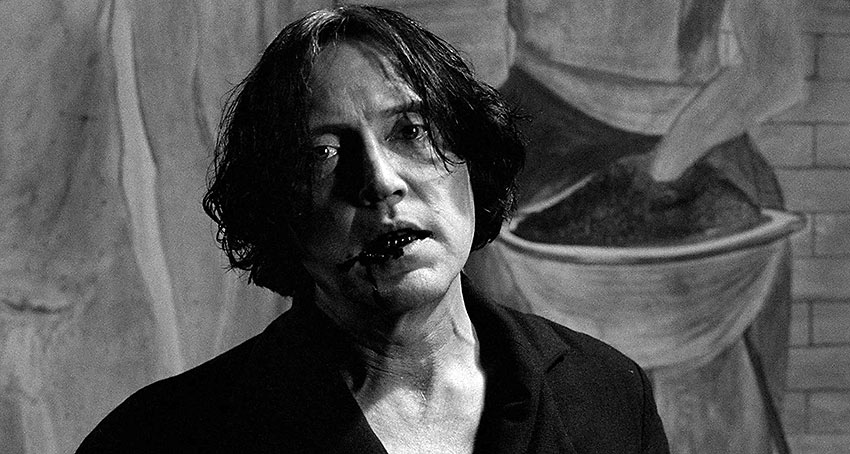

Of course, it wouldn’t be a Ferrara film without a few indecent-to-objectionable jabs — here, documentary shots of rows of corpses from My Lai, the Nazi death camps and the former Yugoslavia. Taste aside, this overkill violates the scale of the narrative, and contributes virtually nothing. Even so, Ferrara’s tenth feature is his best-directed yet. His typically gritty thrust is everywhere apparent; so is a new desire for carefully shaded dynamics. Keen touches abound: the surprising use of rap music, or the way Peina and Kathleen are prevented from appearing in the same shot as he strips her of her defenses. The black-and-white cinematography of Ken Kelsch (another longtime Ferrara team member) works the boundary between wakefulness and dream, stunningly framed and lit but never fussed over.

Lili Taylor has been giving excitingly inventive performances for years, but the part of Kathleen is a feast for her and her admirers. She has essayed spiritual rapture before, in Household Saints (1993). But one also gets gleaming sardonic wit, tossed-off erudition, power supported by tissue-thin fragility, and physical suffering so vivid as to leave one gasping.

If Christopher Walken is a little too perfect for Peina, he doesn’t coast on obvious attributes; his urgency implies that the character has been waiting a lifetime to impart what he knows. Edie Falco is flinty and touchingly steadfast as Kathleen’s best friend. And Annabella Sciorra cuts a stylish swath as the original assailant. Lean and chillingly mean, it’s hard to credit this persona to the actress first seen in True Love (1989).

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.