Directed by: Jack Cardiff

Directed by: Jack Cardiff

Writers: André Pieyre de Mandiargues (novel), Ronald Duncan (screenplay)

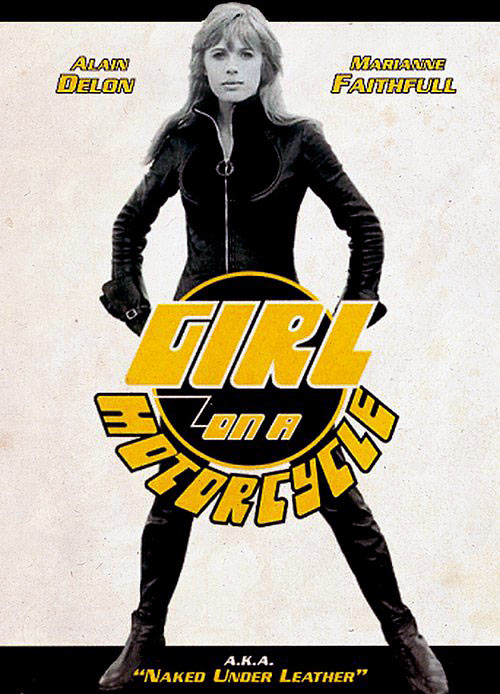

Cast: Marianne Faithfull, Alain Delon, Roger Mutton

Cinematography by: Jack Cardiff (photographed by), René Guissart Jr. (as René Guissart) (lighting cameraman)

The Girl on a Motorcycle

By Walt Mundkowsky

“For the first time in the pub all the men noticed her. She had the sensuality of opposites — the youth and experience, the leanness and voluptuousness, which invited both protection and sadism.”

— Nicholas Mosley, Impossible Object

The Girl on a Motorcycle (Warner Bros. – Seven Arts) is not a title likely to attract studious filmgoers, and on the whole it is perhaps just as well. But the movie succeeds at what is seldom attempted — re-creating a poetic novel’s imagery in visual terms.

That novel is The Motorcycle (1966) by André Pieyre de Mandiargues, on its own small scale a masterwork. If it reminds one of anything in cinema, it might be the films of Resnais: extreme technical confidence and refinement, behavior informed with a strong sense of ritual, jumps through time and space which deepen one’s understanding of events, formal completeness. Rebecca Nul, the 19-year-old wife of Raymond, a dull, passive French schoolteacher, leaves his bed early in the morning and squeezes into a fleece-lined black leather jumpsuit (“Skin, it’s like skin. I’m like an animal”). She roars off on her motorcycle to see her lover Daniel, a commanding fortyish intellectual who is a librarian (in the film a professor) at the University of Heidelberg. He gave her the enormous black Harley as a sardonic wedding present. During the ride from Haguenau, in Alsace, across the border to Heidelberg, Rebecca recalls her four-month affair — it’s twice as long as her marriage. Finally reaching the outskirts of Heidelberg, she is killed in a highly poetic collision with a truck.

The book was called porn, even by some of its admirers; if they meant the unstinting celebration of the erotic, the tag was apt. The motorcycle, really the main character, is “a tempest subject to its rider, who controls it at her caprice by a tiny movement of her foot or hand and thus its rôle is subordinate and reduced to that of a procuress in the service of a great predator.” At times, though, the machine becomes more than the symbol and projection of Daniel and could replace him — “She felt the rhythm of the explosions in the center of her belly as under the crown of her skull, and since she had closed her eyes she experienced once again the impression formerly and painfully suffered at the dentist’s of being unremittingly subject to a strident and perforating machine.” Singular metaphors abound. When Daniel ravished Rebecca in the snow, “she saw herself burnt by the fire of a stake, like a saint or a sorceress.” Afterwards “He detached her hands from their supports with a gentleness and a gravity which would not have been out of place in handling a dead body.” The approach is cool, immaculate, unsettling.

Jack Cardiff, who directed and photographed, was an imaginative and versatile cameraman; while none of his subsequent films as director is genuinely first-class, Sons and Lovers (1960) remains a much better shot at filming Lawrence than the wildly exalted Women in Love — Trevor Howard’s Walter Morel is a performance to treasure — and all his work is dotted with stunning images. Here he has allowed some surprising problems to go unchecked. Most obvious are the trashy psychedelic effects that mar the fantasy sequences and tone down the more daring sex scenes. This violates the novel’s purpose, which is to present the bizarre rising out of the commonplaces of everyday life. The poor back-projections add their bit of annoyance. The structure, largely from the book, fails to affect one as it should; the flashbacks, and flashbacks within flashbacks, are strangely unobtrusive — nothing more than a convenient way to organize the material at hand. In the novel, the free and random-seeming associations strike sparks off each other; they count for much more than themselves. An abrasive, detached score would have been a great help, but Les Reed’s music is one long blare.

The main fault lies elsewhere. The adaptation (Cardiff), screenplay (Ronald Duncan) and interior monologue (Gillian Freeman) all but undo the film at the start. In the book “she felt relieved, as though of her own will she had abolished them by turning the acceleration grip.” It becomes “A twist of the throttle and I obliterate this muck — and turn myself on.” When the screenwriters are not making the source crude and prosaic, they are overturning it. As Rebecca enters the café, “no one shows any sustained curiosity about her, no one seems to notice the singularity of her appearance, its oddness in such a place”; in the film she could hardly cause more of a stir if she walked in naked. Daniel tells Rebecca, “Your body is like a violin in a velvet case,” a line rightly given in the book to the unimaginative Raymond. These may not seem crucial, but the novel is an accretion of details, moods, nuances, tones; consistent lapses unravel the whole.

They keep trying to “explain” the characters, to provide each of them with a dossier of motivations and traits. Rebecca’s essence is a void, “she had been and would always be no more than an object in transit.” The film transforms her into a Mod creature, anti-war and pro-rebellion. Her internal conflicts are flattened into movie conventions — “I married him as a protection against you. I tried to make him happy.” Scenes nicely handled are sometimes hammered to death. When Daniel sneaks into the hotel room, assaults Rebecca and leaves without a word, she has to add, “He didn’t even look back.” Yes, we noticed.

Equally damaging is stuff not in the book, Raymond losing control of his geography class and Daniel conducting a seminar discussion of free love; they would be wrong even if brilliant, which they aren’t. (The point about Daniel is his veiled complexity.) The tinted stock shots of motorcycle racing (Daniel is an enthusiast) also misfire: What’s important is not the subject but how his words move Rebecca (“and above all the meticulous daredevil John Surtees, the driver with the seminarist’s manners, for whom he confessed to a special admiration”).

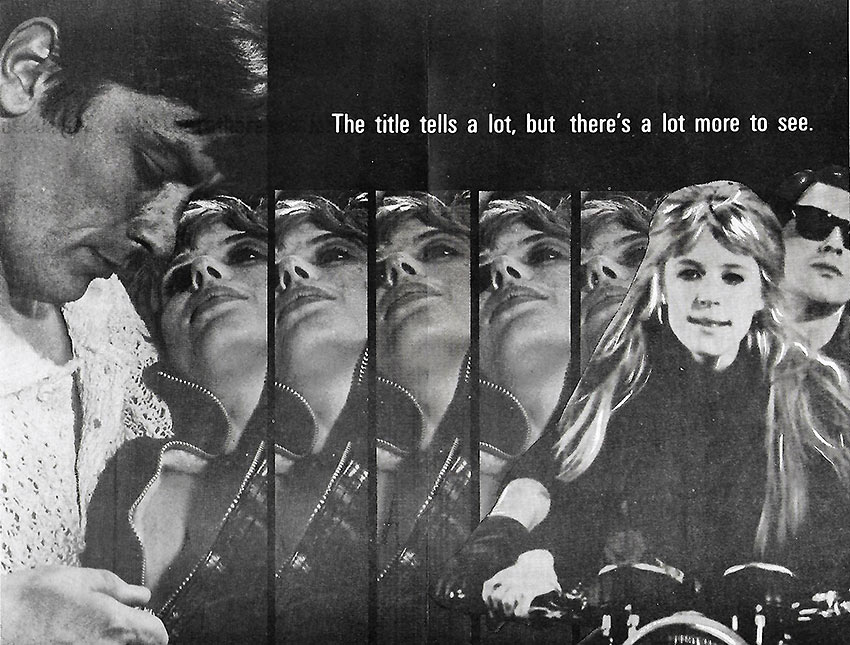

What can be held up against all this? If Cardiff the writer / director falls flat, Cardiff the photographer triumphs. The camerawork, particularly in the exteriors, grasps the core of a novel much concerned with the surfaces of things. Take the first shot after the credits, of Rebecca’s fog-shrouded house; the colors — Nicolas de Staël grays, really — are so undefined they seem about to run together. Or the confrontation with a hostile customs official, the focus shifting from Rebecca’s anxious face to “a rather curious ring he is wearing on his third finger, a tiny silver serpent with a body striated to represent scales, the head nastily flattened” and back again. Obviously Cardiff has taken great care to preserve the book’s imagery, which makes the writing all the more bewildering. The tracking shots past mist-covered cemeteries, statues of military heroes, and towers truly convey a sense of doom; hard to believe that anything good ever happened in such a place. “I must ask Daniel why bridges all look like mousetraps,” Rebecca muses, and the accompanying subjective shot traveling down the bridge appears endless; the distortion carries a claustrophobic charge. Some interiors are striking, like a love scene played out in front of a rain-spattered window running the width of the screen, in diamond-hard light.

In a clumsily shot disaster, we know that an extreme long shot equals Lyrical. Such shots here of the speeding mechanical brute are lyrical because Cardiff has an eye for the tensions between landscapes and people. These are among the finest things in the film: a long camera pan as Rebecca hurtles across a towering bridge and turns down a road running alongside the river, the motorcycle frequently obscured by girders, fences, trees, buildings; roaring across an overpass as a train clatters by underneath; her image reflected by a block of glassy flats as she whips past. The ending is up to the strangely tranquil violence of the book — “An exorbitantly smiling space is about to swallow her up (and contemplates her with an infinite delight, which is the equivalent of a limitless melancholy), a human or superhuman face, the last, perhaps the true face of the universe.” Rebecca glances off the side of a truck and is rocketed headfirst through the windshield of an oncoming car. Two angle shots of the crumpled motorcycle. The camera withdraws from the fiery accident, moving back and up. Shots of empty, quiet Heidelberg streets are intercut with the camera moving slowly toward the tower clock striking eight in the morning.

The story does not require much in the way of acting, which is fortunate. Aside from her long blonde hair, Marianne Faithfull is quite the Rebecca I had imagined; her scant range of technique suits this part. Cardiff makes telling use of her face — soft and childishly sweet in her father’s bookshop, aggressive and proud on the motorcycle, both hurt and ecstatic with Daniel. Alain Delon is a peculiar choice for Daniel; horn rims and a pipe do not an intellectual make. (Was Bruno Cremer not available?) Roger Mutton does okay with Raymond, and Jacques Marin has a deft moment as an admiring gas station attendant.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.