Why don’t we all know Spanish?

Nationwide, efforts are underway to make education more practical — to teach the skills best suited for economic viability. Much of this is regional; for example, a company requiring specific capabilities partnering with local colleges to equip students with those skills. Meanwhile, President Donald Trump has proposed a litmus test for new immigrants that includes English proficiency. Though his immigration reforms are flawed, it’s undeniable that English fluency provides expanded options for employment and assimilation.

But by definition, assimilation means absorbing new information and experiences into our lives. It need not be a one-way street.

Latinos comprise about 17 percent of America’s population — easily the largest group whose traditional language isn’t English. The figures are higher in New York City with nearly 28 percent, and 20.5 percent on Long Island.

California takes the prize with about 14.99 million Latinos living in the state, edging out 14.92 million English language speakers.

Moving toward a Spanish-fluent society would reap benefits, from business opportunities to cultural cohesiveness.

For many, our professions include regular contact with clients, partners and others whose first language isn’t English. It’s also worth noting, despite Trump’s efforts at downplay and denigration, the still-interdependent trading relationship between the United States and Mexico.

Spanish also is valuable in sales and other blue-collar sectors. An outsized portion of the metropolitan area’s patients and consumers claim Spanish as a first language. Conversing with consumers in their native tongue is a selling point; in expanding industries such as health care, it’s also a safety issue.

Cultural benefits are equally vast. With Latinos comprising so sizable a percentage of our area and nation, a one-way language mandate between large swaths of U.S. residents no longer makes sense. Though assimilation into America’s melting pot has, should and will continue to include learning English, this needn’t come at the expense of common-sense practicality.

The streets don’t lie: Restaurant signs, car radios and sidewalk banter showcase that Spanish has become our homeland’s unofficial second language. Inflexible sentiments of English-only assimilation contradict both our cultural openness and the spirit of American innovation.

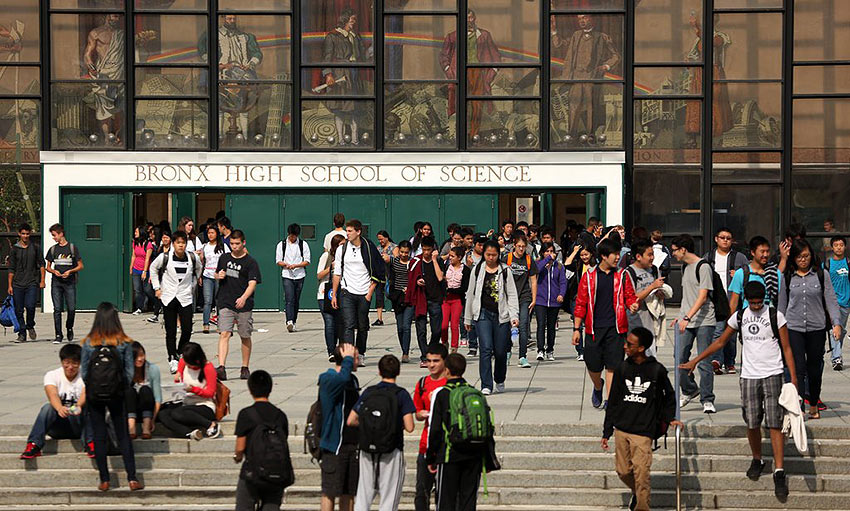

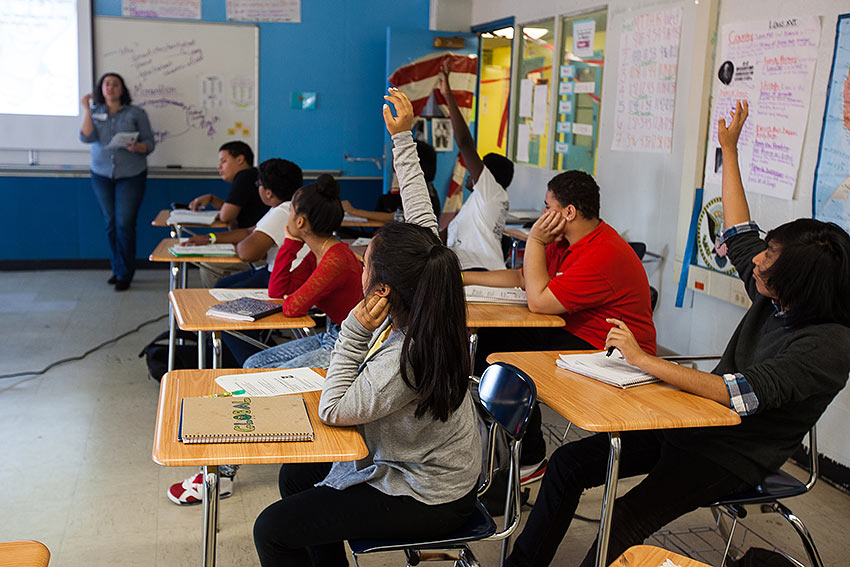

The key to fluency lies in our schools, where Spanish should start earlier and continue longer. Other languages should be offered, too — but in addition to Spanish. This sort of practical precedence would lead to far more students graduating high school with Spanish language mastery rather than baseline, easy-to-forget familiarity.

Ontario, Canada, whose neighboring province of Quebec claims French as its primary tongue, has an effective, imitable second-language system. Students there take compulsory French from grades four through eight and, in high school, they can take immersion classes that teach other subjects only in French. These courses encourage sink-or-swim proficiency — a fast track to fluency.

Census figures suggest that by 2020, more than half of U.S. children will be non-white. New York City is already there: Of its 1.1 million public school students, nearly 41 percent are Latino — just shy of the total percentage of Euro-American and African-American students combined. Even without compulsory Spanish, the United States will likely have more Spanish speakers by 2050 than any other country, even Mexico.

Census figures suggest that by 2020, more than half of U.S. children will be non-white. New York City is already there: Of its 1.1 million public school students, nearly 41 percent are Latino — just shy of the total percentage of Euro-American and African-American students combined. Even without compulsory Spanish, the United States will likely have more Spanish speakers by 2050 than any other country, even Mexico.

Nationally, and especially locally, trends point to an American future told in Spanish as well as English. Our schools should embrace the opportunity — and duty — to prepare children for that future, one already unfolding before our eyes and ears.