In Robert Flaherty’s brilliant 1934 documentary film, Man of Aran, we see an Irish man smashing limestone rocks to bits, while his wife gathers seaweed from the shore below the island’s steep windswept cliffs. Meanwhile, their young son scavenges for animal manure and precious particles of dirt that have collected between the rocks, blown from the mainland. These four ingredients will be used to create the soil in order to grow potatoes – the family’s main source of subsistence. This is the Aran Islands; a landscape made almost entirely of solid limestone rock. It is a landscape that is so cruel and unforgiving that this poor Irish family must manufacture their very own soil in order to survive. When Flaherty first heard of these stoic people, he knew that their lives fit his theme of cultures fighting for their existence against extreme conditions, and that someday he would make a film about them. When I first viewed his masterful documentary, I knew that I too would someday set foot on the islands. Twenty-years later I finally did.

Back Story – Still Mysterious

Nestled on the western coast of Ireland in the middle of the Wild Atlantic Way, the Aran Islands consist of three separate islands: Inishmore, Inishmann and Inishere. Resting approximately seven miles from the mainland, history to tells us that the Aran Islands were untouched by humans for thousands of years. Virtually nothing is known about the first inhabitants, but it is believed the islands were largely covered by forests, which were cut down to use as fuel and building materials. Unfortunately, this left the soil unprotected and rapid erosion occurred. Analysis of the soil indicates that these early islanders’ solution to the problem was (as listed in first paragraph) to mix seaweed, sand, and animal manure to create soil. When not fishing or farming, early Celtic islanders constructed monumental stone forts at the islands’ most strategic points. Later, when Christianity came to Ireland, churches and monastic sites were built out of stone. The population peaked at around 2500 people before the Irish Famine destroyed the major staple crop of potatoes. Interestingly my life-long islander guide informed me that the Famine never touched the islands. The contrasting points-of-view is typical when in Ireland as one is never quite sure who to believe, but does add to the mysterious nature of the islands.

Today

The islands are easily accessible by ferry from Rossaveal (which is the port when coming from Connemara & Galway) and from Doolin, which is close to the Cliffs of Moher in County Clare. There is also a small flight service to the Aran Islands. Locals no longer create their own soil and reliable electricity has come to the Aran, but the islanders – the most rugged-looking people that I have ever encountered – are a hospitable group who are proud to share their history and culture with you. Tourism is now their largest form of income, and visitors come from all over the globe to experience this unique world of primitive forts, medieval churches and dramatic scenery. For centuries, islanders spoke only Gaelic, but today’s residents are fluent in both Irish and English, using Irish when speaking amongst themselves and English when interacting with visitors. Due to their isolated location at the very edge of Europe, the Aran Islands are naturally detached from the rest of the world and have maintained unique customs and ways of life for centuries.

With a population of around 900 people, Inishmore (Inis Mór – the Big Island) is the largest of the Aran Islands, approximately eight miles-long by two and a half-miles wide. If you have just a day, this is the island you must see. Its principal village is Kilronan where you’ll find tour guides, horse drawn carriages and bicycle rentals waiting as soon as you get off your ferry. The Aran Islands’ relatively flat landscape makes an ideal setting for walkers of all levels, while the 30-minute bike ride from the pier to Dún Aonghasa is one of the most popular cycling routes in all of Ireland. Before you depart on your tours, stop by Ionad Arann Heritage Centre, a three minute walk from the village of Kilronan, an excellent visitor’s center, which provides a good introduction and guided tour taking you back more than two thousand years in the life and times of the Aran Islands.

The center demonstrates the art of currach making – a traditional island boat made by stretching a fabric over a sparse skeleton of thin wooden/wicker laths, then covered in tar. The currach has been used on the islands for centuries and is designed to battle the rough seas that face the open Atlantic Ocean. Flaherty was fascinated to find that the Aran fishermen would not learn to swim, since they knew they could never survive any sea that swamped a currach, and would drown without a struggle. His filming of the dramatic shark-hunt – whose liver the islanders would boil to make lantern oil – was a centerpiece of his staged documentary.

The most impressive site on all of the islands is Dún Aonghasa (anglicized Dun Aengus), a 14 acre semi-circle stone fort positioned on the edge of a cliff that falls 300 ft. straight down into the ocean. It is enclosed by three massive stone walls, complete with a remarkable network of dagger-like limestones set vertically outside the walls to deter attackers. To this day, no one is quite sure of the origins of this mysterious stone fort. Excavation has revealed extensive evidence of human activity dating back over 2,500 years. And, yes, the views are stunning.

The most rock-like of all the islands, Inishere (Inis Óirr – The East Island) is also the smallest of the three islands with a population of 300 people, but there are still plenty of attractions to experience. The three primary settlements are Baile an Chaisleáin (Castletown), Baile an Feirme (Farm-town) and Baile an Lorgain (Town of the shin-shaped hill). Monuments include the ruins of Saint Kevin’s Church and O’Brien’s Castle, a 15th century tower house that stands within a stone fort. An important Christian pilgrimage site is Tobar Éanna, the holy well of St. Enda, patron saint of the Aran Islands.

Inishmann (Inis Meáin – The Middle Island) is the least tourist-oriented of the Aran Islands, but is still an important stronghold of traditional Aran culture. Highlights include the ancient Kilcanonagh Church and the oval stone fort of Dun Chonchubhair.

What to Buy

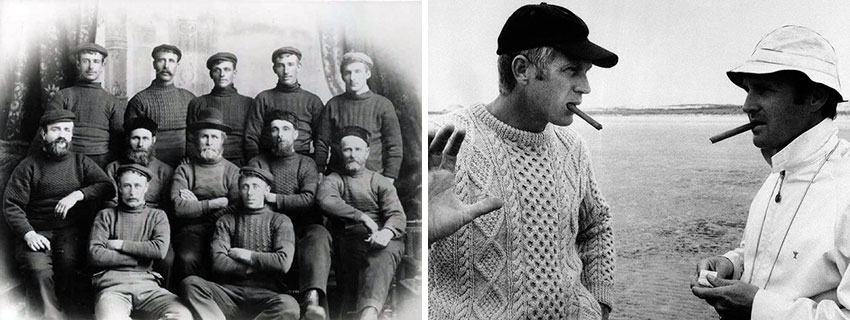

The islands are the home of the iconic Aran sweater (known to many as simply ‘the Irish fisherman sweater’). An authentic Aran sweater is made with undyed cream-colored bainin sheeps wool, and is knitted with unwashed wool that still contains natural sheep lanolin, making it water-repellent. It consists of approximately 100,000 painstakingly constructed stitches, and can take the knitter up to sixty days to complete. There is debate about when island residents first started making the sweaters, but the popular story is that each family had a sweater with their own design. When a fisherman drowned and later his battered body washed-up on the shore, he could be identified by the stitch on the sweater. Once again, my guide told me that this was just another example of a romanticized myth. But as John Ford once said, when the legend becomes fact… always print the legend. After all, this is Ireland where myths and folklore only add to the charm and legacy of the Celtic people. The same textured knitting patterns are often used to make socks, hats, vests and even skirts and make wonderful gifts. Make sure that you ask the seller if the sweater was made on the island, for factory-made ones from Galway are starting to be sold at some of the shops. I even found one made in Cambodia.

How to Get There

Aer Lingus has direct flights from LAX to Dublin and Shannon airports. Rent a car, but remember that not only do you drive on the left side of the road, but almost all cars are manuals – so make sure you request an automatic if not you’re not comfortable shifting with your left hand.

Go here for more information on travel to the Aran Islands

Before you go, check out the new book: The Aran Islands: At the Edge of the World, researched and edited by Paul O’Sullivan.