“Madam, women do not wear wigs, for they are the working class, like me,” chides the slightly salty Irishwoman Mary Murray, a gifted, master wigmaker in 18th-century Williamsburg, Virginia. “Ladies, on the other hand” she continues, “can wear wigs. What makes a lady is: She either comes from money, marries money, or buried him recently. Which one are you?”

My reply: None of the above, I muse. But, as I chat with Mistress Murray, I soak up her keen observations on life in Colonial Williamsburg, navigating my way through her brogue; I learn very quickly that she is an especially hard worker, who puts in long hours, crafting wigs for the wealthy and status-seekers of the period. Because, indeed, owning a wig (or, better still, a whole cupboard full of them), was a universally recognized symbol of wealth and status. She tells me that a mere five percent of the Virginia population could afford a wig — and those who could were likely to be tradesmen, merchants, clergy, military men, ship captains, and landed gentry. She further explains to me that the longer the wig, the more costly, of course; hence, the term “big wig” came into popular usage, denoting a person with clout, status, and — dare we say? — significant means.

As an Irishwoman working in a British colony, she does not have an easy time of it, but her skills are so in demand, that she is forgiven her national heritage. She is a magician at crafting wigs and a font of knowledge on her chosen profession: She shows me how to curl a wig, using a forged-metal tool, which is constructed with a pair of round finger grips and a split blade (sort of like a pair of scissors). The circular grips are wrapped with cording to prevent burning the user’s fingers, as the iron is heated before use to better coax hair into curls and waves. She further tells me that she gets her “supplies” from goats, horses, and yaks. And another tidbit: Wig wearers usually shave off their actual hair — makes wearing wigs easier and more hygienic.

Of course, Mary is but a corporeal imagining (with the help of historical research), brought to life by local resident Betty Myers, who is a seminal “interpreter” in the wig shop. She is a passionate player in the cast of interpreters who embody Colonial Williamsburg’s inhabitants — shop owners, tradespeople, soldiers, government officials, and patrons. Betty has been a cast member since the late ’80s. She is emblematic of the dedicated interpreters who thoroughly research their characters, their jobs, and their lives. Indeed, everything here is period-perfect.

And that is just as it should be, as Colonial Williamsburg — the onetime capital of this colony — was conceived to accurately represent the period as flawlessly as possible: It is a living-history “gallery,” the largest outdoor museum in the country, bringing to life 18th-century America throughout its 300-acre campus. It is the passion project of the Reverend Dr. William Archer Rutherford Goodwin, who secured the financial backing of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., in the late 1920s, to bring his dream to life. The actual site comprises several hundred restored or re-created buildings — 88 of which are original — from the 17th through the 19th centuries. The main Historic Area is a National Historic Landmark and, indeed, if you step onto the main thoroughfare, Duke of Gloucester Street (referred to as DoG Street), you will feel as if you have taken a journey in a time machine back into America’s infancy.

Colonial Williamsburg is administered by the private Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, which is dedicated to maintaining the Historic Area buildings, trades shops, and museums. Throughout the year, the Foundation offers educational programs, theatrical presentations, lectures, how-to classes, holiday-themed happenings, and so on, and is dedicated to the conservation and preservation the art and artifacts in the Historic Area. There is even a wardrobe shop that produces authentically constructed garments for the interpreters — down to the most minute details, like hand-crafting intricate death-head buttons for military uniforms.

During one three-day visit two years ago, I was faced daily with so many choices of what to do — nearly thirty offerings each day — that I had a tough time choosing: “Secrets of the Chocolate Maker,” revolving around 18th-century recipes; a visit with the famous barber of York, Caesar Hope, who tells his life story of slavery and enterprise; a lecture on Ben Franklin’s greatest invention, the glass armonica; a tour of the stables (called Bits and Bridles); the official Colonial Williamsburg Ghost Walk; and during another visit, I had an opportunity to view a highly educational theatrical presentation, “Resolved: An American Experiment Tour,” in the Capitol Building.

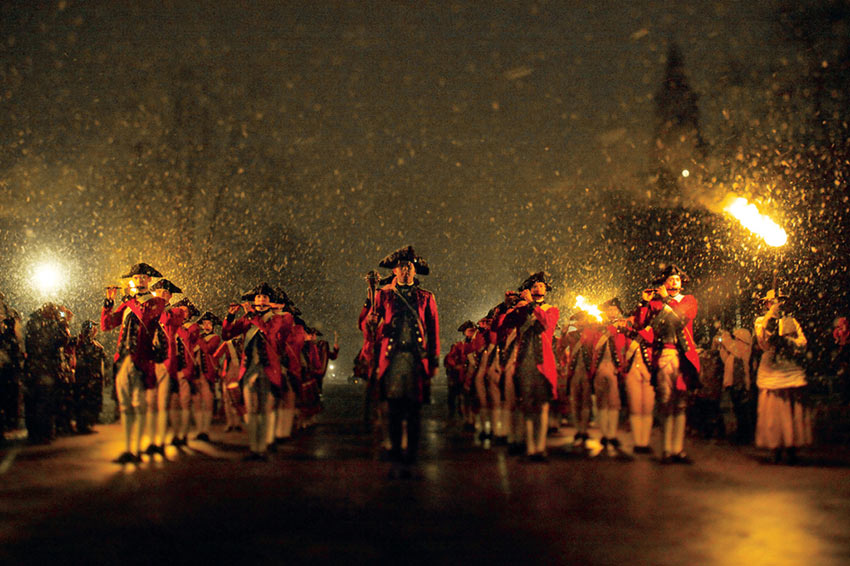

A year before that visit, I was able to attend the “Grand Illuminations” weekend (this year, it will be held December 4-6), the highlight of which is a re-enactment of the kind of “illuminations” (the firing of guns and fireworks) that occurred in Colonial celebrations. The December holiday weekend marks the official beginning of the Christmas season in Colonial Williamsburg and is traditionally observed in a grand way. That night, we toured the Governor’s Palace by candlelight and took part in a military ceremony on the Palace Green. It is a very special weekend, when the entire town is decked out in Colonial finery. This year, because of the pandemic, the celebrations are spread out over many weeks — and capacity is reduced. (If you are planning a trip, check the websites for updates.)

No visit to Colonial Williamsburg is complete, either, without a meal or two in the authentic eateries. Christiana Campbell’s Tavern was allegedly one of George Washington’s favorites, and I loved my period-inspired roast beef luncheon at Shield’s Tavern, as well as a classic Colonial dinner at Chowning’s Tavern. These roadhouse-eateries create menus that reflect the kind of cooking and spices used in the era and the restaurants are staffed by knowledgeable cast members, who also offer up anecdotes and historic trivia. I also learned that in Colonial times, taverns were not mere eateries, but rather hostelries, which also offered lodging and overnight accommodations for travelers’ horses.

Visits to tradespeople’s workshops are also a treat, a brief dive into retro shopping: I spent at least an hour with the cobbler who told me he works by sunlight only (as they did yesteryear — no electricity, of course!), and so in the winter, he knocks off early. I spent another hour with the weaver, learning about the textiles she was making; another hour in the Margaret Hunter Millinery and Mantua-Maker Shop, chatting with the Mistress herself, brilliantly portrayed by Janea Whitacre, who has worked at Colonial Williamsburg since the early ’80s. The shop sells many things that we would never expect to find in a millinery shop — things more likely to be on offer in the 20th-century in an eclectic “notions” boutique — walking sticks, playing cards, navigational equipment, fans, patent medications, even tobacco! After my visit with Mistress Hunter, I rounded out the day with stops at the apothecary, the silversmith, the bookbindery, the cabinetmaker, and the tin shop. Even then, there were still many more shops I wanted to view.

You will not run out of things to do, either. And if you have time to extend your trip, then you need to take in much more that the Greater Williamsburg Area also offers: the Tasting Trail, which has stops at several wineries (among them, the Williamsburg Winery), breweries (including the wonderful Virginia Beer Company), and even a distillery that makes mead, a fermented-honey-based Colonial-era brew (the Silver Hand Meadery); the Taste Studio, which is equipped for culinary lessons and demos, at the Williamsburg Inn; the recently renovated American Revolution Museum at Yorktown; the York Battlefield; the College of William and Mary (the second-oldest in the America); Historic Jamestowne; the Jamestown Settlement; and even “entertainment experiences,” like Busch Gardens.

© 2020 Ruth J. Katz All Rights Reserved

Liz

August 6, 2021 at 9:11 am

That’s my daughter in the top photo! The photo is 20 years old now — how cute that they’re still using it! I was looking for tips on planning a trip back to Virginia, and there’s my kid

Raoul

August 7, 2021 at 2:35 pm

Why hello Liz. What a fun surprise. Your daughter is very photogenic. Thanks to Colonial Williamsburg, many can appreciate her young “modeling career.” I’m sure other websites have used her picture as well. In behalf of Traveling Boy, thanks to you and your daughter.

If you have a more recent photo of her, please share so our readers can see how she looks now.