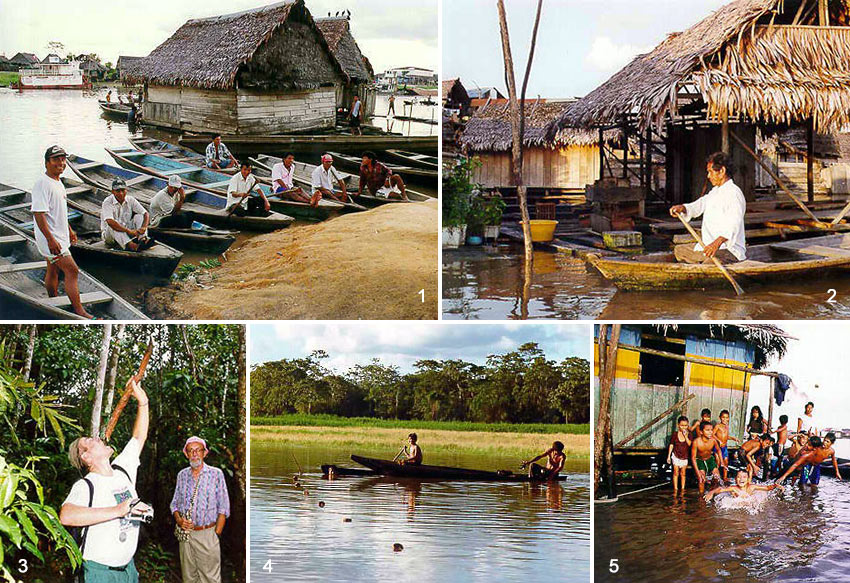

A speedboat departs the Iquitos slums, which hover over the water on stilts and rafts to accommodate mercurial high-water marks that vary 15 meters with the Andes snowmelt. Devouring Peru’s Amazon for several hours, the boat slows as it enters the tributary Yanayacu that snakes through the jungle like an anaconda.

The tranquil waterway leading to the uttermost ends of the Earth flows somber under an overcast sky. Joseph Conrad would have gone for it. Villages disappear, but after every few bends in the river, I can see Indian fishermen netting or gigging catfish, from armoured ones that can “walk” on dry land, to giants that can swallow a small pig. My destination, Loving Light Amazon Lodge, keeps a shaman on retainer. I seek his vision.

An endless palette of greens shifts in light filtering through cloud patterns and treetops. With 11 times the water volume of the Mississippi, the river system moistens the strongest lungs of the earth. As ill-advised development schemes narrow species diversity, jungle shamans are also endangered. These medicine men and spiritual leaders carry rain-forest knowledge accumulated by countless generations. Most villages are now without a leader. Remaining shamans are elderly, and do not have apprentices. As they die, libraries burn. This blows an ill wind for modern medicine, which acquires many of its clinically useful prescription drugs from the rain forest and the realm of folk medicine. Of 80,000 Amazon plant species, only a fraction have been thoroughly analyzed.

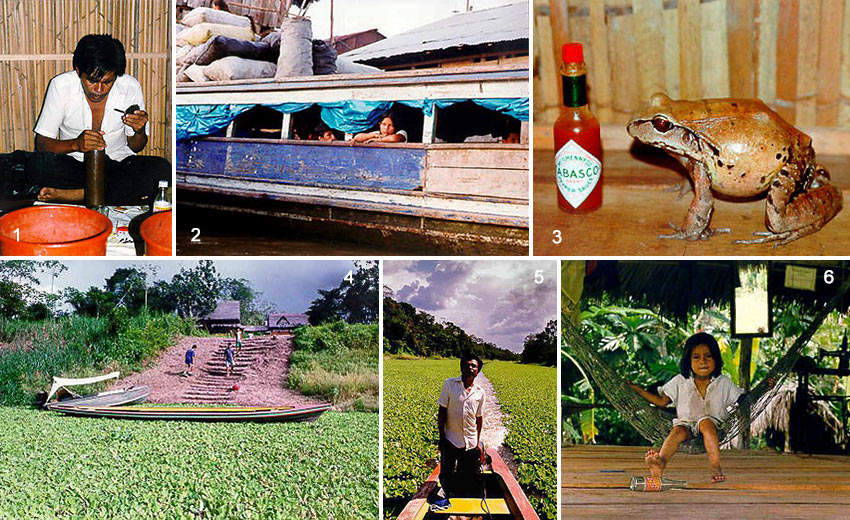

One shaman hanging tough is Marcelino Nolorbe Talexio. Third generation and in his mid-30s, with hopes for his son to join the mystic guild, he looks like an Indian James Mason. Talexio’s house specialty is Ayahuasca, the Inca “vine of the dead, vine of the soul.” Boiling down a species of Banisteriopsis vine and a half-dozen other plants, he produces a potent mix of hallucinogenic alkaloids, used for millennia to enter sacred supernatural worlds for worship, healing and insight.

In the meantime, my fellow travelers and I spend several days gathering our jungle rhythms. We occupy the day with plant lectures, drinking water from one vine, climbing another, and avoiding one caustic enough to burn skin. Traveling the river and adjoining lakes, we take in the local village life that revolves around the river. Children in a one-room schoolhouse sing for us, then play soccer in a jungle clearing. A woman we visit downriver climbs down the high riverbank with several children. They carry parasols and wear pained looks. She lost a child the week before, another is down with fever. A simple gift of ibuprofen is gratefully accepted. The small mounds in a family graveyard, marked by tall yellow and scarlet plants, betray the Amazon’s sadness – high mortality for children.

At night, we hunt tree tarantulas. Is it the brown or the black that really nail you? Whichever, it’s the opposite for scorpions. Or we paddle in suspenseful search of caimans, alligator-like reptiles whose glowing eyes don’t betray their actual size. Our boat guide’s hands move with startling speed, tossing small ones into the boat that unnerve those wearing sandals. Small, colourful frogs land in our arms, one leap ahead of the repeated query, “Is this a poison dart frog?”

Fishing for the legendary peacock bass requires special tackle – one quickly takes my lure like an hors d’oeuvre and keeps going. But piranha are a no-brainer – eat ’em before they eat you, that’s my motto. Actually, you can swim and bathe in the river as long as you’re not bleeding. The tough part is retrieving the hook from the razor teeth of a decent-sized piranha. The best implement I’ve found is an Indian carving of a phallic symbol, although hook removal sends a shiver.

And best not to get caught in a downpour while fishing. Sheets of rain pound our long dugout canoe as lightning slices the gray horizon, thunderclapping applause and layering dread on the faces of the young Indian couple guiding me. We bail wildly until comically pitching our metal pots to the far end of the canoe, as if lightning is so choosy. No jumping to land, either – the thick reeds on this river section hide vipers and, the speedboat long gone for supplies and the shaman who knows where, I chance lightning in preference to the bushmaster and his cousins.

The night of the vision quest finally arrives. The house band – singing guitarist, a maraca shaker and a bongo player – warm up Peruvian blues of unrequited love as we light lanterns and ponder a dinner spiced with a side dish of yellow seed pod sauce known as “monkey-dick.” Offered by the chef with a sly look, its memory alone makes my face sweat.

The ceremony is in a huge, thatched dome roundhouse, with wraparound windows covered by mosquito netting. Those not participating wisely retire to the deck porch overlooking the river, with the exception of the American lodge partner, the designated lifeguard this night.

Talexio begins by blowing tobacco smoke into a soda-pop bottle filled with muddy grey glop, topping off the foulest, vilest tasting brew to cross my lips. How bad? Large, red buckets sit ominously in front of the newly initiated, just in case.

He settles into a five-hour rendition of his Ayahuasca Icaro. An Icaro is a shamanic power song learned from an elder or from the spirits, intended to provoke visions. The song alternates with a melodic whistle while brushes woven from reeds carry the beat on our heads and shoulders, rapping on the door between the inner self and the rain forest.

Nothing. Wait, there’s a shot left over. The shaman spies my move, his eyebrow starts rising, but he’s too slow on the draw. Still, nada.

Ticked at having drunk that gunk to no apparent effect, muck so foul no monkey-dick could fix it, I stand up. I sit down. The jungle’s cacophony of night sounds blend into the shaman’s song, which I hug like a life raft. Skepticism over the shaman’s mental alchemy vanishes as the forest reaches out to my senses while the night’s lightning storms play on the horizon like distant artillery.

The chaotic onslaught of the jungle coalesces into an inclusive organic wave washing over me, imparting the reverence with which many locals view their surroundings. What a loss to lose this relationship. I mull over private thoughts until sunrise.

I’ll share one. My father was a traveling salesman with a well-received megawatt smile. Our bond cemented around riding horses on weekends and vacations where his LeSabre, replaced every two years with phenomenal miles logged, navigated the West in a week. He drove hundreds of miles across Kansas at a fast clip to just make a high school wrestling match. Our relationship strained during the Vietnam protests but I felt lucky to have it. Insights often came from around the corner, a tear while watching “Death of a Salesman.” Born in 1907, his life was interrupted by WWII, when he was second in command on a Navy ship. So dad was in his mid-forties when his only child was born. Some kids confused him with my grandfather. My father died a few years before my Amazon sojourn, just after the birth of my daughter – I think he struggled to hold on until then. I felt I never had time to grieve.

The shaman’s brushes chased away molten pools of gold. Suddenly my father was with me. Arm in arm, we strolled about the circular chamber – which gained size with every step – sheltering us from the thunder and lightning outside. He was a young man I’d never known.

His face matched a large oval portrait photo I’d found in a farm attic, from when he was called “Slim” and “Red”. He wore a straw boater style hat. In real time, I was a generation older than he was during his visit, but that night my years rolled off, too – a peer, a pal. I don’t recall words, but communications were clear as a bell. A smile speaking volumes. Immensely satisfying. Joyful. Fantastic.

In the morning, we gather for the shaman’s debriefing. We describe our visions to a translator and hear the shaman’s analysis. The shaman sips a mixture of rum and garlic, blowing it onto the back of our heads as he sings and whistles and beats about our heads and shoulders with brushes. Sobering.

Talexio takes the helm of a long dugout and we journey down the Yanayacu to the Amazon for a rendezvous with pink river dolphins. They bob around us, like they’re waiting to play a game of Marco Polo. Mixed with their grey brethren, they look as if some crazed interior decorator named Kurtz had gone up river in the ’80s and then gone terribly wrong in the heart of darkness. Hot and weary from the night’s rigours, we swim in the cool murky waters, but the dolphins keep respectful distance. Local mermaid legends undoubtedly originated with the pink dolphins, fueled by a local’s cane-juice horror.

Swimming off the broad expanse of a river beach one easily imagines caimans, electric eels, big fish with fins like daggers and pesky piranha. They don’t concern me. My frontal lobes are captive to the legend of the Candiru, the Toothpick Fish. This tiny parasitic catfish is said to navigate warm urethra canal currents. Once upstream, he secures his berth with open fins. Wrapped like an onion, I sport two swimsuits and all my dirty underwear. If the Candiru gets me, it would only be as an overwrought metaphor for the civilization I have sought refuge from.

Flocks of ducks fly low in formation along the river as we begin the long voyage back up the Yanayacu. Our all-purpose shaman tends the precious motor rigged onto our dugout. Despite strong currents, floating plants form a thick pea green soup. Approaching storm clouds turn the sky steel gray. Not to worry, my shaman is at the rudder.

Suddenly, Talexio looks sheepish. The dugout stops, then drifts backwards. The shaman, who does Ayahuasca four or five times a week, forgot to fill the gas tank. The dugout has one paddle. Night falls.

Lightning flashes and the rain comes. A flashlight beam lights a caiman’s eyes. The beer runs out. “Before we die, what is the lesson, O shaman?” I ask with a sneer.

“Manten tus pantalones bien puestos,” he replies, reading my earlier fit of fright with the Candiru. Roughly translated, it means, “Keep your pants on.”

Loving Light Amazon Lodge: Extremely remote and rustic, but pleasing, with a minimum of layers insulating visitors from the environment. Medical personnel stay for free at Loving Light on any day they spend half their time tending the needs of area villages. Major medical volunteer missions elsewhere in Peru’s Amazon can be organized through the Rainforest Health Project in Washington State (

rh*@po***.com

).

Don’t travel down the Yanayacu to bushwhack through the jungle in search of Loving Light enlightenment. You might instead brighten an anaconda. This reprise from the Wayback Machine is in memoriam to Loving Light. Years ago some locals sold off the lodge wood piece by piece without notifying the stateside owner – choose management carefully – a sad loss making this a glorious but brief place in the space/time continuum. Gone but not forgotten, the lodge moved to the Twilight Zone.

Growing up in Kansas, Skip Kaltenheuser was tuned to travel by a traveling salesman father’s pedal to the metal vacations. He extended his reach with travel writing, and efforts such as supervising elections and doing special projects. When they’re willing to slum with him, Skip’s favorite travels are still with one or both kids, now young adults, neither indicted despite living in Washington, DC their entire lives.

Growing up in Kansas, Skip Kaltenheuser was tuned to travel by a traveling salesman father’s pedal to the metal vacations. He extended his reach with travel writing, and efforts such as supervising elections and doing special projects. When they’re willing to slum with him, Skip’s favorite travels are still with one or both kids, now young adults, neither indicted despite living in Washington, DC their entire lives.