The T-Boy Society of Film & Music’s latest poll is devoted to our 20 favorite films of 1971. Part One in the series focuses on films voted by our members from eleven to twenty. Part Two will feature the final top ten.

The genesis of our poll was highly influenced by Christina Newland’s thoughtful piece in BBC Culture, entitled, Why 1971 was an Extraordinary Year in Film.

Ms. Newland writes, In the late 1960s the Hollywood film industry was floundering financially, and many of the struggling major studios were bought out by non-media companies. By ’71, film admission in Hollywood had slowed to less than a quarter compared to the heyday in the 1940s. There was no set path for studios to follow, and no certain road into the future of filmmaking.

When critics and scholars talk about the remarkable artistic flowering that came from the “New Hollywood” of the ’70s, it’s often about how artists slipped through the cracks in the chaos between the old guard fading away and the new guard taking over. By 1971, this seemed to be precisely what was occurring.

Yes, we agree with Ms. Newland’s assessment that the abundance of unique 1971 films were the tip of the iceberg, where young Hollywood filmmakers responded to the decline of U.S. optimism, reflected by the political assassinations of JFK, Bobby Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and the continuation of the amoral War in Vietnam, complete with napalmed children and unpunished U.S. war criminals a fixture on the evening news. The studio brass was confused, and it seemed that anyone who was young with long-hair and a beard was handed a camera to make a movie. But, keep in mind, most of the new films were of literary content, not necessarily form or visual style.

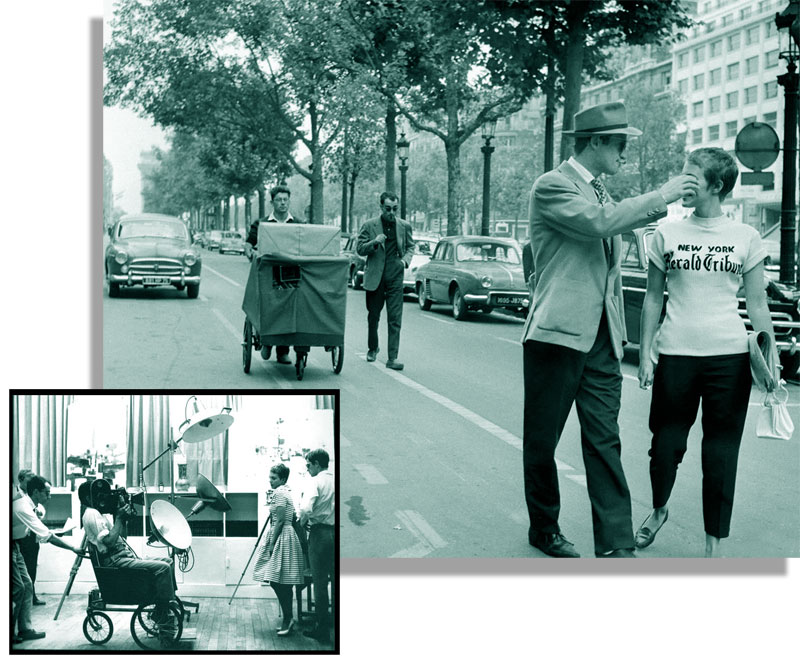

So, it’s important to note that the young Hollywood directors were highly influenced by the French Nouvelle Vague’s use of new lightweight cameras and sound equipment, natural lighting and high-speed film which allowed shooting on the streets, as director Jean-Luc Godard and photographer Raoul Coutard once did when they pushed a hidden camera in a shopping cart while filming Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg on the Champs-Élysées in À bout de souffle (1960).

But, the Nouvelle Vague influences – similar to how Italian Neorealism effected the French filmmakers – did initially impact the early visual style of certain new Hollywood directors; in particular Francis Ford Coppola, John Cassavetes, Arthur Penn, Jack Nicholson, Martin Scorsese, William Friedkin, Hal Ashby and Brian De Palma. Akin to the Beatles and the British Musical Invasion of the 1960s who taught us to appreciate our own music, the Nouvelle Vague did the same with our Hollywood movies with many of its filmmakers previously film critics on the journal Cahiers du Cinéma, who had an understanding of the works of Hollywood masters such as Hitchcock, Hawks and post-Citizen Kane films by Orson Welles. In Peter Biskind’s landmark text, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, he explains that Warren Beatty first offered the screenplay of Bonnie and Clyde to Godard and Truffaut before Arthur Penn, which reinforces the influence of La Nouvelle Vague on the new Hollywood directors; where Godard himself is considered the most influential filmmaker of the post-World War 2 era.

But, with that said, our list of top films of 1971 is not made at the expense of established masters such as directors like Don Siegel, Stanley Kubrick, Franklin J. Schaffner.

So, once again, the T-Boy Society of Film and Music’s list of our 20 favorite films of 1971 begins with Part One; films from eleven to twenty.

Initial Comments:

- For me, it’s all about change, realism (not the aging studio, “shot-on-the-backlot” attempts at realism). – Jim Gordon, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- I spent much of my time at college in the dark, at a movie theater steps away from my apartment. A roll of ten tickets cost ten dollars. That might have been the best investment I ever made, because I honestly believe I learned more from these and other films I saw there (a special nod to Bergman, Truffaut, Fellini, Rossellini, and Visconti) than I did from all that fancy education. – Stephen Brewer, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- Fifty years ago, with both the industry and wider society in turmoil, an astounding set of movies was born – which offer pause for thought about cinema today. Amid US films, there was often a fascinating split between pro-establishment works and those which embraced the spirit of the counterculture. – Christina Newland, BBC Culture

- Violating the boundaries between life and art to make their material their own was a dangerous way for these filmmakers to work. It was successful for a while, enriching both the life and the art, but as the two became more extravagant and interchangeable, New Hollywood directors lost the detachment of artists, and their lives and art sank into quicksand, joined in a fatal embrace. – Peter Biskind, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls

- “Born again Christian” Johnny Cash was asked why he recorded a cover version of the Nine Inch Nails’ song ‘Hurt,’ which focused on heroin addiction. His reply was simple: “A good song is a good song.” That echoes my selections of films that stand alone devoid of 1971 cultural and literary sensibilities. – Ed Boitano, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- A movie is a movie is a movie. – Alfred E. Newman, Mad Magazine

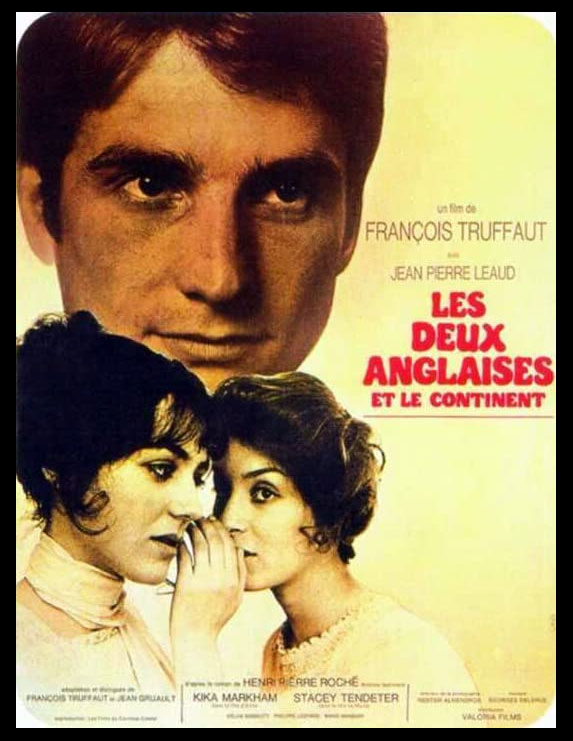

Number 20: TWO ENGLISH GIRLS

Director: François Truffaut; Writers: François Truffaut, Jean Gruault (adapted from Les deux Anlaises et le continent by Henri-Pierre Roché); Cinematography: Néstor Almendros; Music: Georges Delerue; Film Editing: Martine Barraqué, Yann Dedet; Production Design: Michel de Broin; Costume Design: Gitt Magrini.

Players: Jean-Pierre Léaud, Kika Markham, Stacey Tendeter, Sylvia Marriott, Marie Mansart, Philippe Léotard, Mark Peterson, David Markhm, Georges Delerue (the film’s music composer in small role).

Synopsis:

At the beginning of the 20th century, Claude Roc, a young middle-class Frenchman meets in Paris, Ann Brown, a young Englishwoman. They become friends and Ann invites him to spend holidays at the house where she lives with her mother and her sister Muriel. During the holiday, Claude, Ann and Muriel become very close and he gradually falls in love with Muriel. But both families lay down a one-year-long separation without any contact before agreeing to the marriage. So, Claude goes back to Paris where he has many love affairs and sends Muriel a farewell letter.

Memorable Line:

Stacey Tendeter as Muriel Brown (in letter): Dearest Claude, I came to see you to bury this thing. I’m glad you were the first, because it’s you, because you wanted it. I shan’t cry. Listen to me as you once did when I told you love was stirring in me. Now I tell you that it must die. So that I may live.

Extras:

- Truffaut had earlier adapted another Henri-Pierre Roché novel, Jules and Jim.

- Anne’s last words in the film are, If you send for a doctor, I will see him now. These were writer Emily Brontë’s last words before she died. We assume that Truffaut probably used her words in the film as an homage or to compare her to the character of Anne.

- Jean-Pierre Léaud ultimately appeared in seven films directed by Truffaut.

Critics:

- Truffaut’s “Two English Girls” is a film of such beautiful, charming and comic discretion that it isn’t until the end that one realizes it’s also immensely sad and even brutal, though in the non-brutalizing way that truth can sometimes be. – Vincent Canby, NY Times

- As a man obsessed with memories of the past, Truffaut continues with his tradition of period pieces. Even many of his contemporary genre films feature flashbacks to earlier days. – Ringo Boitano, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- Because Truffaut doesn’t strain for an emotional tone, he can cover a larger range than the one-note movies. Here he is discreet, even while filming the most explicit scenes he’s ever done; he handles sadness gently; he is charming and funny even while he tells us a story that is finally tragic. – Roger Ebert, RogerEbert.com

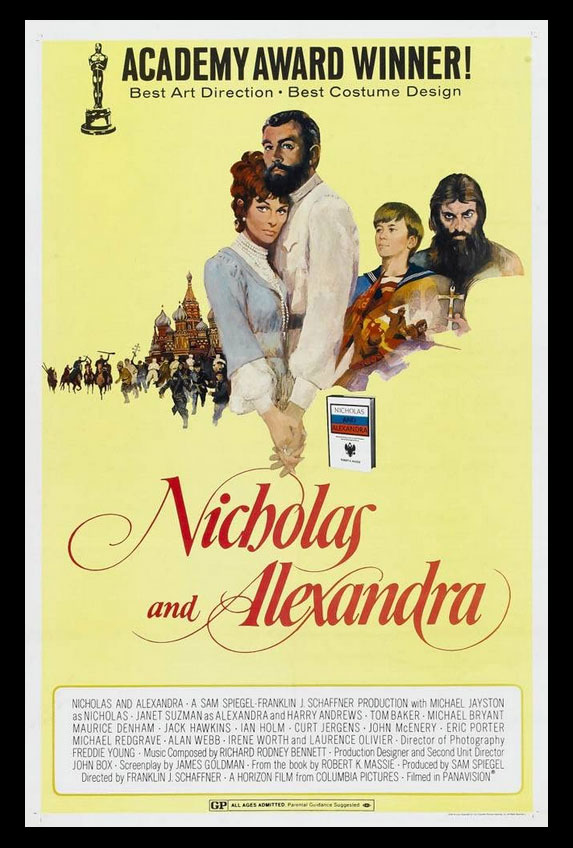

Number 19: NICHOLAS AND ALEXANDRA

Director: Franklin J. Schaffner; Writing: James Goldman, screenplay (based on the book by Robert K. Massie); Cinematography: Freddie Young; Film Editing: Ernest Walter; Production Design: John Box; Art Direction: Ernest Archer, Jack Maxsted, Gil Parrondo; Costume Design: Yvonne Blake.

Players: Michael Jayston, Janet Suzman, Ania Marson, Lynne Frederick, Candace Glendenning, Fiona Fullerton, Tom Baker, Jack Hawkins, a young Brian Cox as Trotsky, and Daniel Day Lewis (uncredited).

Synopsis:

Tsar Nicholas II, the inept last monarch of Russia, insensitive to the needs of his people, is overthrown and exiled to Siberia with his family.

Memorable Line:

Michael Jayston as Tsar Nicholas II: The Russia my father gave me never lost a war. What shall I say to my son when the time comes? That I had no pride? That I was weak? I’ve always thought God meant me to rule. He put me here. He chose me, and whatever happens is His will. We shall fight on until victory.

Extras:

- Tsar Nicholas II was the first cousin of Great Britain’s King George the 5th and Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm the 2nd.

- Director Franklin J. Schaffner deliberately cast unfamiliar leads (Jayston, Suzman, Baker) so the audience would focus on the storytelling.

- Schaffner had Michael Jayston, Janet Suzman, Roderic Noble, Ania Marson, Lynne Frederick, Candace Glendenning, and Fiona Fullerton live together during filming so that the actors would form a family-like bond, in an effort to make their scenes together more authentic.

Critics:

- The writing is excellent. “Nicholas and Alexandra” is a slice of history and intriguing. – Richard Carroll, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- There’s always a kind of fascination in royalty. We democratic Americans even seem to like royalty more than those nations who have some. Nicholas and Alexandra may not have been the flashiest of czars and czarinas, but maybe they weren’t entirely to blame; the muted tone of the age was set by Queen Victoria, who (as Vincent Canby notes) was the grandmother of practically everybody in World War I – Roger Ebert, RogerEbert.com

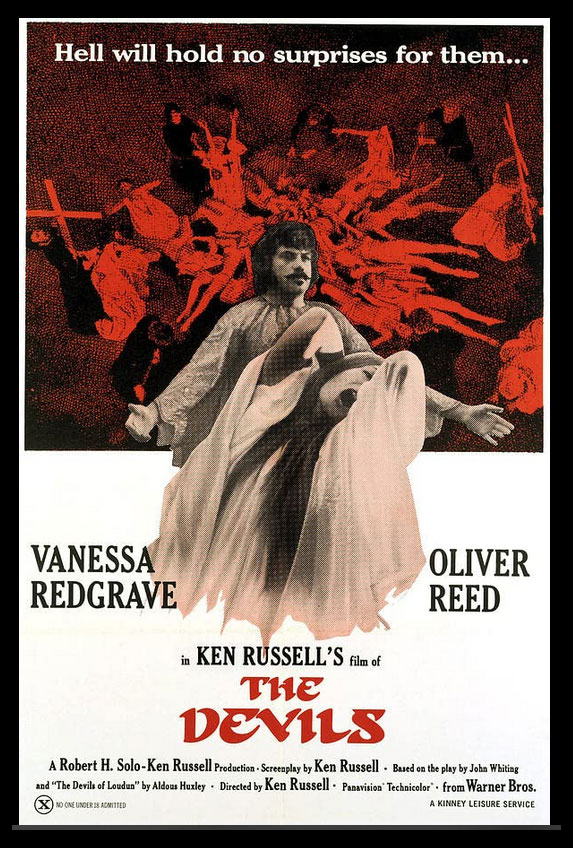

Number 18: THE DEVILS

Director: Ken Russell; Writing: Ken Russell, screenplay (based on the play by John Whiting & novel by Aldous Huxley); Cinematography: David Watkin; Music: Peter Maxwell Davies; Film Editing: Michael Bradsell; Art Direction: Robert Cartwright; Costume Design: Shirley Russell; Set Design: Derek Jarman.

Players: Vanessa Redgrave, Oliver Reed, Dudley Sutton, Max Adrian.

Synopsis:

In 17th-century France, Father Urbain Grandier seeks to protect the city of Loudun from the corrupt establishment of Cardinal Richelieu. Hysteria occurs within the city when he is accused of witchcraft by a sexually repressed nun.

Memorable Lines:

Oliver Reed as Grandier: Lies! Lies and heresy. The Devil is a liar, and the father of lies. If the Devil’s evidence is to be accepted, the most virtuous people are in the greatest of danger, for it against these that Satan rages most violently. I had never set eyes on Sister Jeanne of the Angels until the day of my arrest, but the Devil has spoken, and to doubt his word is sacrilege.

Vanessa Redgrave as Sister Jeanne: Oh, Christ, let me find a way to you. Take me in your sacred arms. Let the blood flow between us uniting us.

Grandier: My lords, I am innocent of the charges. And I am afraid. But I have the hope in my heart that, before this day ends, Almighty God will glance aside and let my suffering atone for my vain and disordered life. Amen.

Extras:

- Soon to be a director in his own right, Derek Jarman’s sets are modeled on Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927).

- Ken Russell wanted to avoid the clichéd look of period films and insisted on anachronistic, even futuristic, design.

- Russell’s guidance to Jarman was that it should echo the ‘rape in a public toilet’ line from the Huxley novel that inspired the film.

Critics:

- Two years before “The Exorcist” hit the screen, Ken Russell puts the Catholic Church in the spotlight by filming one of the most disturbing films of all times. Except from being a sheer technical and aesthetic masterpiece, “The Devils” provokes as a film with its relentless sense of anarchy. Religious hysteria and illusions, the horror of human arrogance and depravity and the love that turns to cherishing that turns to hatred. – Vassli, IMDB.com

- Though Russell wrote the screenplay for “The Devils” his scripts and by others are only a starting point for him to transcend his own personal vision. Frustrating for many, but glad he was around. – Ed Boitano, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

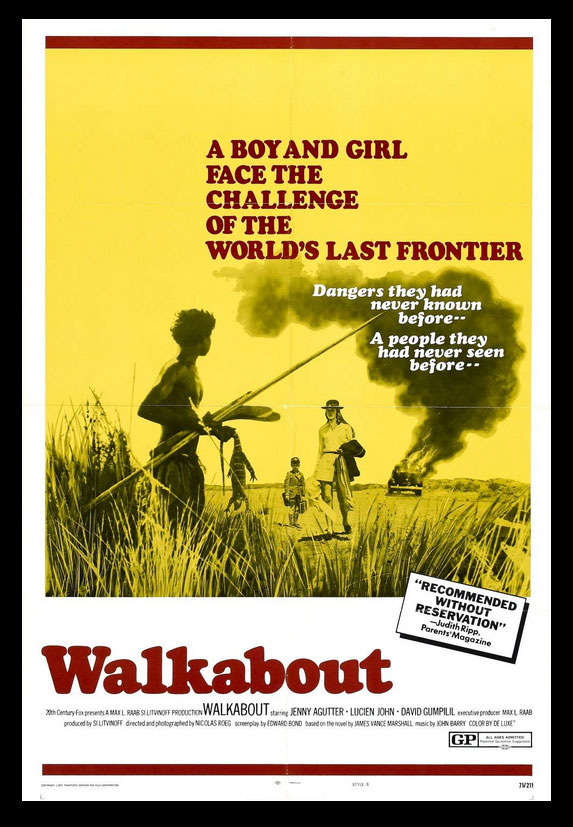

Number 17: WALKABOUT

Director: Nicolas Roeg; Writing: Edward Bond, screenplay (based on novel by Donald G. Payne and story by Nicolas Roeg); Cinematography: Nicolas Roeg; Music: John Barry; Film Editing: Antony Gibbs, Alan Pattillo; Production Design: Brian Eatwell Art Direction: Terry Gough.

Players: Jenny Agutter, Luc Roeg, David Gulpilil, John Meillon.

Synopsis:

Two city-bred siblings are stranded in the Australian Outback, where they learn to survive with the aid of an Aboriginal boy on his walkabout, a ritual separation from his tribe.

Memorable Lines:

Jenny Agutter as the Girl: I don’t know why you are telling him all this. He can’t understand. He doesn’t know what a ladder is. I expect we’re the first white people he’s seen.

Luc Roeg as White Boy: He didn’t say goodbye to us. The Girl: Yes, he did. That’s what the dance was about. It’s there way of saying goodbye to people they loved.

Narrator (last lines from “Poem XL” by A.E. Housman’s “A Shropshire Lad”): Into my heart an air that kills, From yon far country blows: What are those blue remembered hills, What spires, what farms are those? That is the land of lost content, I see it shining plain, The happy highways where I went, And cannot come again.

Extras:

- In Australia, when an Aborigine man-child reaches sixteen, he is sent out into the land. For months he must live from it. Sleep on it. Even if it means killing his fellow creatures. The Aborigines call it the walkabout.

- In his first screen role, David Gulpilil spoke no English at the time of filming.

- Director Nicolas Roeg’s son, Luc Roeg, in his first film role, was actually sun-burnt in the scene where the aboriginal boy treats his back by rubbing him with fat from a wild boar. Nicolas Roeg thought it would make a good scene for the film so he picked up the camera and shot it.

Critics:

Roeg’s desert in “Walkabout” is like Beckett’s stage for “Waiting for Godot.” That is, it’s nowhere in particular, and everywhere. – Roger Ebert, RogerEbert.com

Roeg revels in the hallucinatory, creating a wilderness that exists as much in the mind as it does the land. – Luke Buckmaster, The Guardian Australia

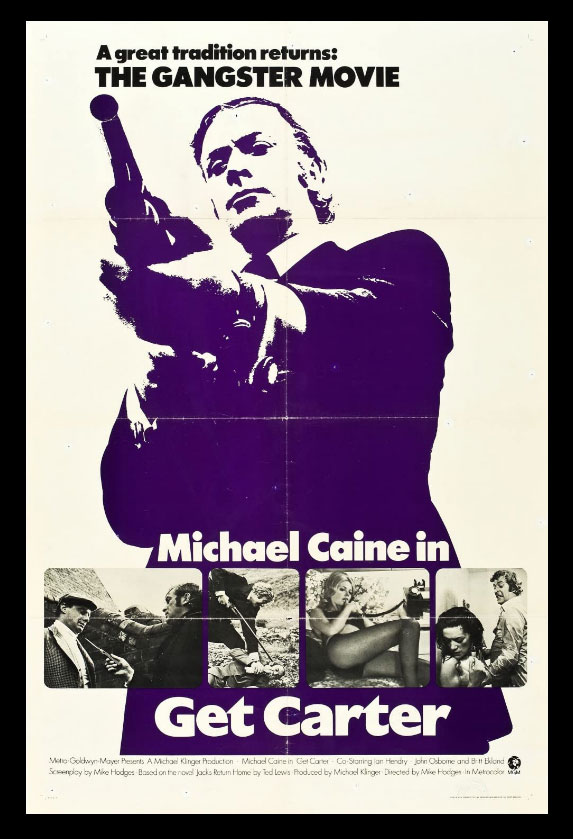

Number 16: GET CARTER

Director: Mike Hodges; Writer: Mike Hodges, screenplay (based on the novel Jack’s Return Home by Ted Lewis); Cinematography: Wolfgang Suschitzky; Music: Roy Budd; Film Editing: John Trumper; Art Direction: Roger King.

Players: Michael Caine, Ian Hendry, Britt Ekland, John Osborne, Tony Beckley, George Sewell, Geraldine Moffat.

Synopsis:

When his brother dies under mysterious circumstances in a car accident, suave London gangster Jack Carter travels to his working-class hometown in Newcastle to investigate his death in this chilling neo-noir.

Memorable Line:

Eric the gangster: So, what’re you doing then? On your holidays?

Michael Caine as Jack Carter: No, I’m visiting relatives.

Eric: Oh, that’s nice.

Jack Carter: It would be… if they were still living.

Extras:

- Mike Hodges’ work was influenced by Raymond Chandler and Hollywood tough guy films such as Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955), as they showed “how to use the crime story as an autopsy on society’s ills.”

- Mike Hodges favored the use of long-distance lenses (as he had used previously on ITV Playhouse: Rumour.

- The role of mobster Cyril Kinnear is played by writer John Osborne, whose play Look Back in Anger ushered in the British cultural movement in the late 1950s and early 1960s, known as the Angry Young Men or kitchen sink realism. The movement changed the artistic landscape of contemporary Britain, which reflected the disillusionment of society, anger and an impatience for change.

Critics:

- Mike Hodges has thrown his actors into real life – the faces of the old men in the pubs and betting shops, and the revelers at the dancehall take the movie into something akin to cinéma verité, even as mayhem erupts in the foreground. – Michael Hann, The Guardian

- No one can play a tough like Michael Caine; a disturbing mix of charm, kindness and savage restitution. – Ringo Boitano, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- “Get Carter” is Hodges’ best film, where the coaly Northeastern English Industrial Revolution town of Newcastle actually serves as a character in the film. Ed Boitano, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

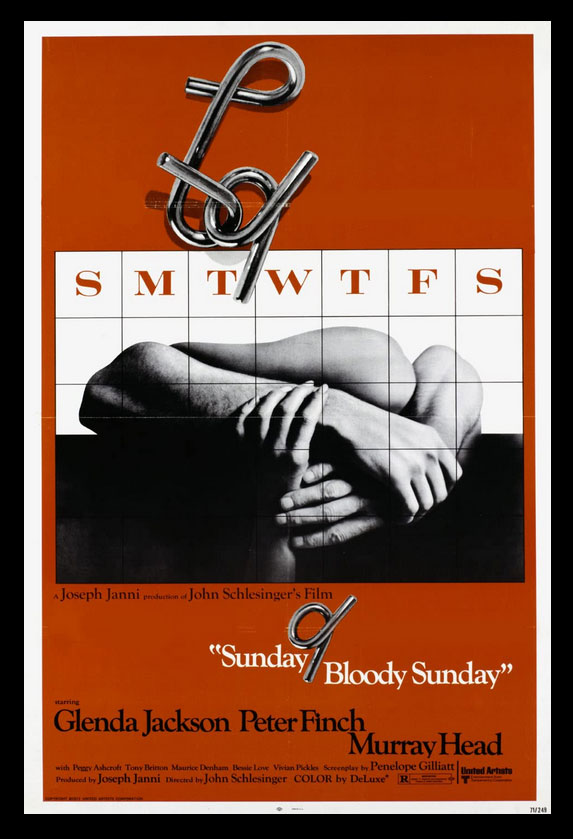

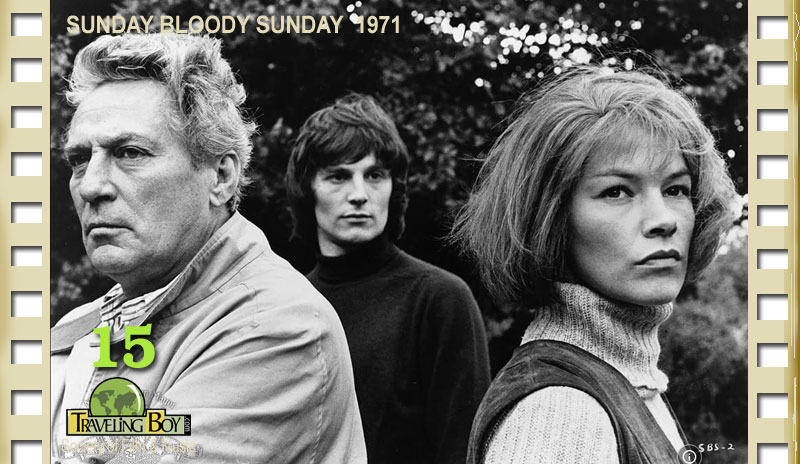

Number 15: SUNDAY BLOODY SUNDAY

Director: John Schlesinger; Writing: Penelope Gilliatt; Cinematography: Billy Williams; Film Editing: Richard Marden; Art Direction: Norman Dorme.

Players: Peter Finch, Glenda Jackson, Murray Head, Peggy Ashcroft, Tony Britton, Maurice Denham, Vivian Pickles, Frank Windsor, Daniel Day-Lewis (uncredited).

Synopsis:

A Jewish doctor, Daniel Hirsh and a middle-aged woman, Alex Greville are both having affairs with the same male artist, Bob Elkin. Not only are Hirsh and Greville aware that Elkin is seeing the other but they actually know each other as well. Despite this, they are willing to put up with the situation through fear of losing Elkin who switches freely between them. Schlesinger’s film highlights some worrying facts about how much people’s attitudes to relationships and each other have changed over just two generations.

Memorable Lines:

Peter Finch as Daniel (speaking to the camera): When you’re at school and you want to quit, people say, “You’re going to hate it out in the world.” Well, I didn’t believe them and I was right. When I was a kid, I couldn’t wait to be grown up, and they said “Childhood is the best time of your life.” Well, it wasn’t. And now, I want his company and they say, “What’s half a loaf? You’re well shot of him,” and I say I know that… but I miss him, that’s all and they say “He never made you happy” and I say, But I am happy, apart from missing him.

Critics:

- A story of a ménage à trois is a sad reflection on settling for less than we want, with London drizzle setting the mood and an onscreen, same-sex kiss crashing through barriers. – Stephen Brewer, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- I think “Sunday Bloody Sunday” is a masterpiece, but I don’t think it’s about what everybody else seems to think it’s about. This is not a movie about the loss of love, but about its absence. – Roger Ebert, RogerEbert.com

- Director John Schlesinger reportedly used the approach associated with Alain Resnais in preparing this film; he asked Penelope Gilliatt, a writer with a definite and highly developed fictional world, to produce an original screenplay, and he influenced the work through discussions but did not contribute a single word himself. – Walt Munkowsky, Traveling Boy, Time Capsule Cinema

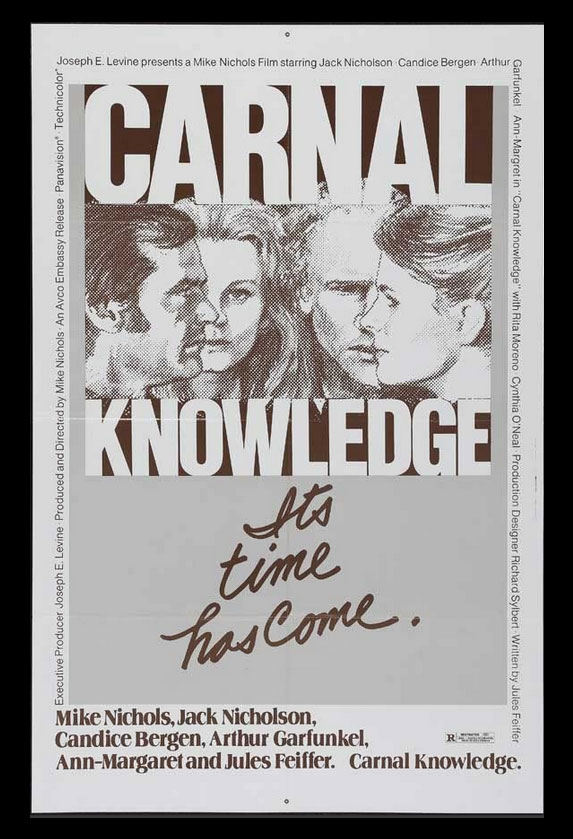

NUMBER 14A (Tie): CARNAL KNOWLEDGE

Director: Mike Nichols; Writer: Jules Feiffer; Cinematography: Giuseppe Rotunno;

Film Editing: Sam O’Steen; Production Design: Richard Sylbert.

Players: Jack Nicholson, Candice Bergen, Art Garfunkel, Ann-Margret, Rita Moreno, Carol Kane.

Synopsis:

Chronicling the lifelong sexual development of two men who meet and become friends in college.

Memorable Lines:

Jack Nicholson as Jonathan (narrating his slide show): Marcia, 13 1/2 or thereabouts, I kissed her one night at a spin-the-bottle party. This one’s Rosalie. Rosalie looked just like Elizabeth Taylor in “National Velvet.” I had a crush on Rosalie from 14 to 15 and I never went near her. In those days, we had illusions. Here’s Charlotte. Not much on looks, but great tits for 15. Here’s Gloria, the best-built girl at Evander Childs. I took her to the Bronx Zoo once and on the bus, copped a cheap feel. Here’s Bobbie! My wife. The fastest tits in the West and king of the ball-busters. She conned me into marrying her and now she’s killing me with alimony.

Extras:

Jules Feiffer said Mike Nichols told him he was considering Jack Nicholson for the role of Jonathan. Feiffer went to see Easy Rider(1969) and thought the guy with the “hip Henry Fonda stance and twangy New Jersey drawl” had nothing in common with “the young Jewish misogynist” at the center of his script. Nichols told him: “Trust me, he’s going to be our most important actor since Brando.”

Critics:

- “Carnal Knowledge”‘ was ahead of its time (as was Mike Nichols). – Jim Gordon, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- The structure of the film, as well as the visual form given it by Nichols (lots of soliloquys in tight close-ups), is that of a Feiffer cartoon, or, more specifically, like a series of cartoons that cover the 1940s (when Jonathan and Sandy are in college), the 1950s (when Sandy is married and beginning to envy Jonathan’s bachelor freedom), the 1960s (when Sandy begins to wander from his suburban paradise), and the 1970s (when the only way in which Jonathan can successfully overcome his impotency is by elaborately pre-arranged masquerades). – Vincent Canby, NY Times

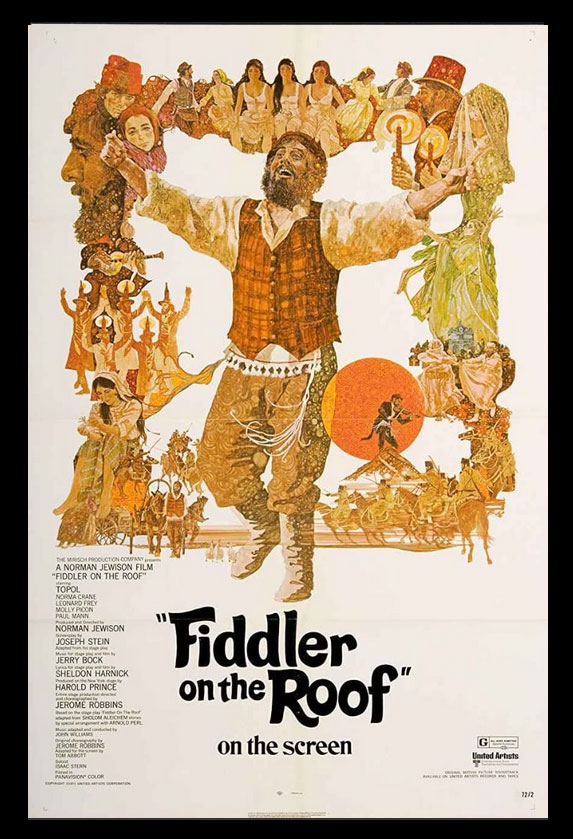

Number 14B (Tie): FIDDLER ON THE ROOF

Director: Norman Jewison; Writing Credits: Joseph Stein, screenplay (based on stories by Sholom Aleichem, with further adaptation by Arnold Perl); Cinematography: Oswald Morris; Music: Jerry Bock (based on music for the stage play by Alexander Courage, and Sheldon Harnick, lyricist for the stage play by Isaac Stern); Music Department: Jerry Bock, orchestrator; Eric Tomlinson, violin soloist; John Williams, conductor and music adapter.

Players: Topol, Norma Crane, Leonard Frey, Molly Picon.

Synopsis:

In prerevolutionary Russia, a Jewish peasant contends with marrying off three of his daughters while growing anti-Semitic sentiment threatens his little village of Anatevka. Among the traditions of the Jewish community, the matchmaker arranges the match and the father approves it. The milkman Reb Tevye is a poor man that has been married for twenty-five years with Golde and they have five daughters. When the local matchmaker Yente arranges the match between his older daughter, Tzeitel, and the old widow butcher, Lazar Wolf, Tevye agrees with the wedding. However, Tzeitel is in love with the poor tailor Motel Kamzoil and they ask permission to Tevye to get married that he accepts to please his daughter. Then his second daughter Hodel (Michele Marsh) and the revolutionary student Perchik decide to marry each other and Tevye is forced to accept. When Perchik is arrested by the Czar troops and sent to Siberia, Hodel decides to leave her family and homeland and travel to Siberia to be with her beloved Perchik. When his third daughter Chava decides to get married with the Christian Fyedka, Tevye does not accept and considers that Chava has died. Meanwhile the Czar’s troops evict the Jewish community from Anatevka.

Memorable Lines:

Topol as Tevye: Traditions, traditions. Without our traditions, our lives would be as shaky as… as… as a fiddler on the roof!

Tevye to God: I know, I know. We are Your chosen people. But, once in a while, can’t You choose someone else?

Tevye: You are just a poor tailor!

Motel: That’s true, Reb Tevye, but even a poor tailor is entitled to some happiness!

Extras:

- Canadian director Norman Jewison was brought into the project by executives at United Artists who thought he was Jewish. His first words to the executives upon meeting them were, “You know I’m not Jewish, right?”

- The title comes from a painting by Russian artist Marc Chagall called The Dead Man which depicts a funeral scene and shows a man playing a violin on a rooftop. It is also used by Tevye in the story as a metaphor for trying to survive in a difficult, constantly changing world.

- To get the look he wanted for the film, Jewison told director of photography Oswald Morris to shoot the film in an earthy tone. Morris saw a woman wearing brown nylon hosiery, and thought, “That’s the tone we want.” He asked the woman for the stockings on the spot and shot the entire film with a stocking over the lens. The weave can be detected in some scenes.

- Morris nabbed the Best Cinematography Oscar for his work.

Critics:

There are some contrived and artificial moments in “Fiddler,” but it becomes more convincing, naturalistic, and involving as it goes on, and finally builds to a powerful climax. It ranks high among the best musicals ever put on film. -Paul Sargent Clark, The Hollywood Reporter

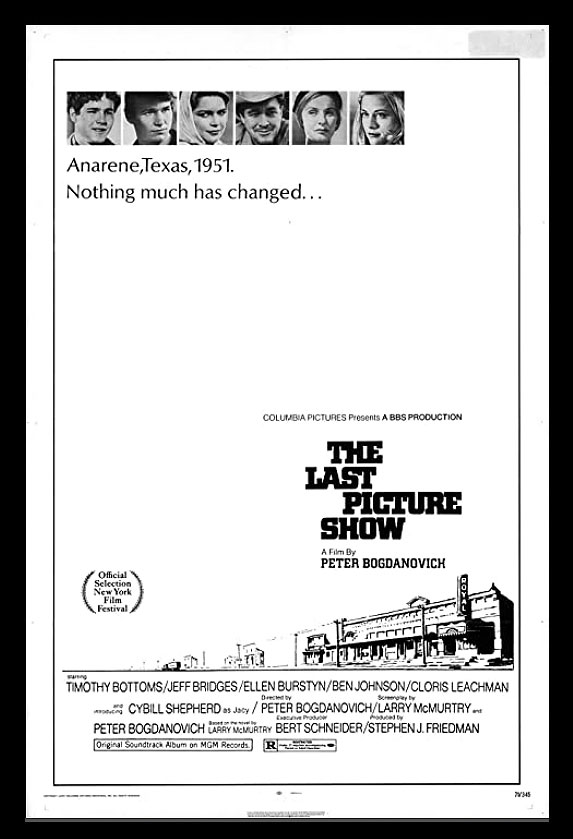

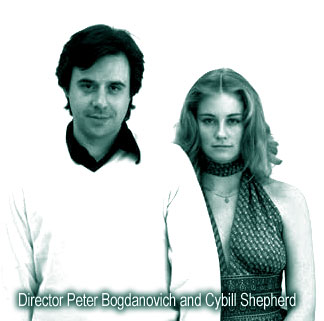

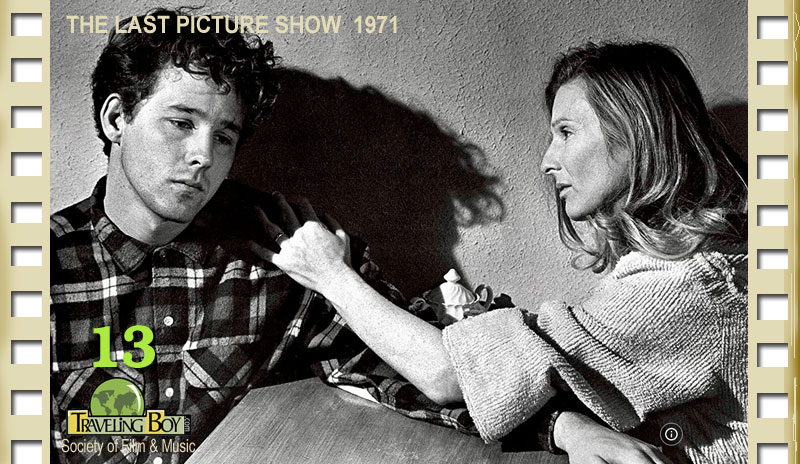

Number 13: THE LAST PICTURE SHOW

Director: Peter Bogdanovich; Writing: Peter Bogdanovich & Larry McMurtry, screenplay (based on Larry McMurtry novel); Producers: Stephen J. Friedman, Bert Schneider; Cinematography: Robert Surtees; Editing: Donn Cambern, (Peter Bogdanovich, uncredited); Production & Costume Design: Polly Platt; Music: Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, Phil Harris, Johnny Standley, Hank Thompson.

Players: Timothy Bottoms, Jeff Bridges, Cybill Shepherd, Ben Johnson, Cloris Leachman, Ellen Burstyn, Eileen Brennan, Clu Gulager, Randy Quaid, Sam Bottoms.

Synopsis:

In 1951, a group of high schoolers come of age in a bleak, isolated, North Texas town.

Memorable Lines:

Ben Johnson as Sam the Lion: You boys can get on out of here, I don’t want to have no more to do with you. Scarin’ a poor, unfortunate creature like Billy just so’s you could have a few laughs. I’ve been around that trashy behavior all my life, I’m gettin’ tired of puttin’ up with it. Now you can stay out of this pool hall, out of my cafe, and my picture show too. I don’t want no more of your business.

Sam the Lion: If she was here I’d probably be just as crazy now as I was then in about 5 minutes. Ain’t that ridiculous? Naw, it ain’t really. Cause being crazy about a woman like her is always the right thing to do. Being an old decrepit bag of bones, that’s what’s ridiculous. Gettin’ old.

Timothy Bottoms as Sonny Crawford: Nothin’s really been right since Sam the Lion died.

Cloris Leachman as Ruth Popper (last line in film): Never you mind, honey. Never you mind.

Extras:

- Ben Johnson was persuaded to accept the role of Sam the Lion by his friend, director John Ford. Johnson had turned the part down three times because, according to Peter Bogdanovich, the part had too many words, but Ford reportedly persuaded him by asking if he only wanted to be playing John Wayne’s sidekick for the rest of his career.

- This film was one of the first to use already popular recordings by original artists to score a film that included songs by Frankie Laine, Hank Williams, Jo Stafford and others.

- Cloris Leachman’s last scene in the movie was printed on the first take without any previous rehearsals. She wanted to rehearse the scene, but director Bogdanovich thought it would ruin the scene if it was rehearsed. After she completed the take, she said to him, I can do better. Bogdanovich replied, No, you can’t; you just won the Oscar. Ultimately his sense of direction paid off, as Leachman won the Academy Award for her performance as Best Supporting Actress.

Critics:

- A relentless look at the banality of life manages to be energizing and affirming. – Stephen Brewer, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- Bogdanovich was more than a director, having embraced the “Auteur Theory” in 1963. With his reviews of earlier Hollywood genre films made by masters, he too taught us much about our own films. – Ringo Boitano, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

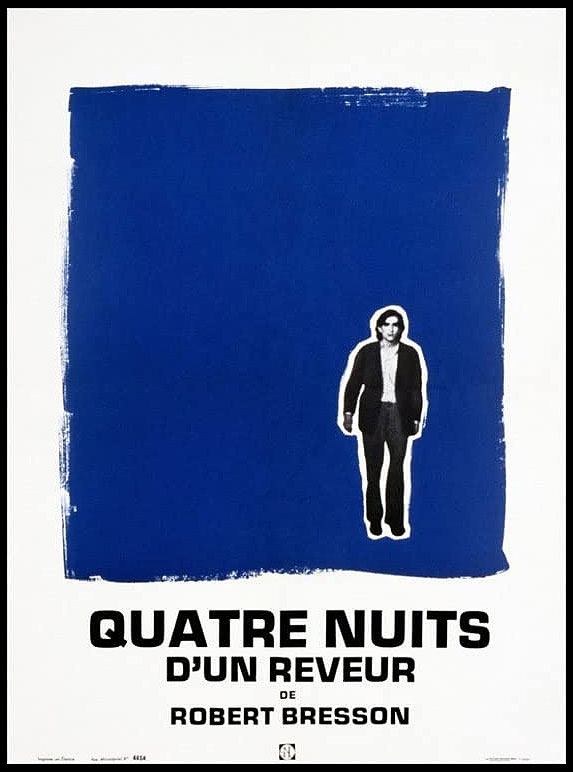

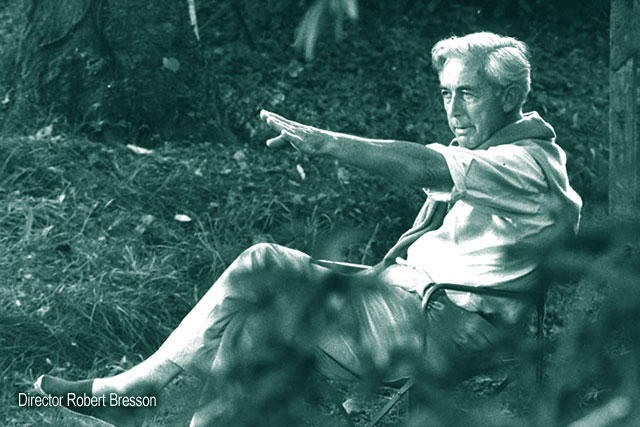

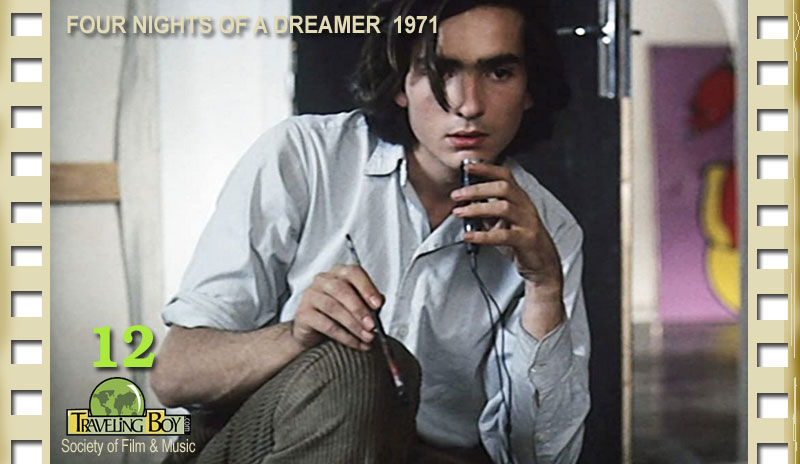

Number 12: FOUR NIGHTS OF A DREAMER (quatre nuits d’un rêveur)

Director: Robert Bresson; Writing: Robert Bresson (loosely based on Fyodor Dostoevsky’s short story White Nights); Cinematography: Pierre Lhomme; Music: F.R. Daid, Louis Guitar, Chris Hayward, Michel Magne; Film Editing: Raymond Lamy; Production Design: Pierre Charbonnier.

Players: Isabelle Weingarten, Guillaume des Forêts, Jean-Maurice Monnoyer, Giorgio Maulini.

Synopsis:

Loosely based on Fyodor Dostoevsky’s short story White Nights, the lead character is Jacques, a young painter, who by chance runs into Marthe as she’s contemplating suicide on the Pont-Neuf in Paris. They talk, and agree to see each other again the next night. Gradually, he discovers that her lover promised to meet her on the bridge that night, and he failed to turn up. Over the next couple of nights, Jacques falls in love with her, but on the fourth night her original lover returns.

Memorable Lines:

Marthe as the woman: ” What’s the matter?

Jacques as the dreamer: ” I love you. That’s the matter.

Extras:

- Two types of films: those that employ the resources of the theater (actors, direction, etc…) and use the camera in order to reproduce; those that employ the resources of cinematography and use the camera to create. – Robert Bresson

- To be constantly changing lenses in photographing is like constantly changing one’s eye glasses. – Robert Bresson

Critics:

- Though considered to be Bresson’s ‘lightest’ film, “Four Nights of a Dreamer” offers an intense emotional experience that began with “Diary of a Country Priest” and ended with his last film, “L’Argent.” Due to the economy of his directorial style, many consider his films slow, when in fact they are remarkably fast. Each image is ironed out, with no image taking on a greater significance than the other. Bresson frees himself from what he calls ‘postcardism,’ which he considers a forced, superficial aestheticism. – Ed Boitano, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- ” Four Nights of a Dreamer” is a rare Bresson film where the mainstream audience actually laughs along with the film as opposed to laugh at it, due to a lack of understanding of Bresson’s deeply personal style. The staged ‘movie premiere’ is the closest he’s ever come to a comedy. – Phil Marley, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

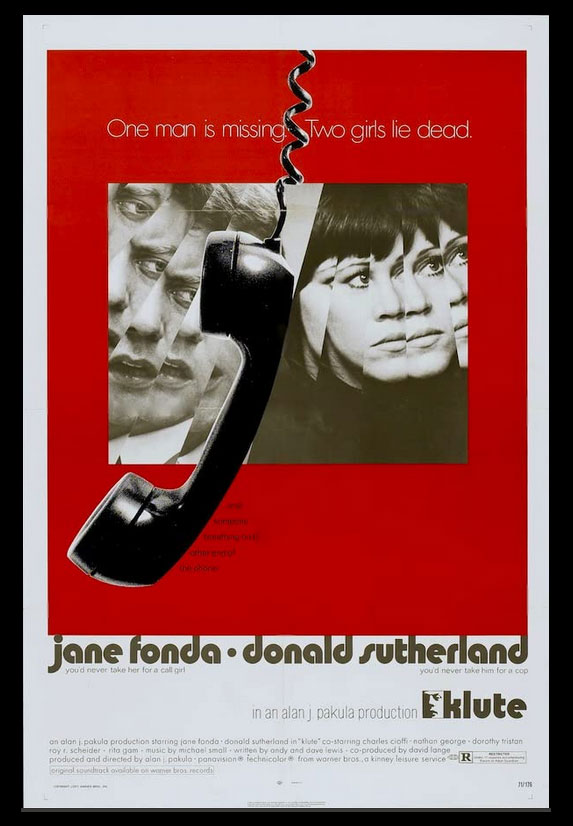

Number 11: KLUTE

Director: Alan J. Pakula; Writing: Andy Lewis & David E. Lewis; Cinematography: Gordon Willis; Film Editing: Carl Lerner; Music: George Jenkins, Michael Small.

Players: Jane Fonda, Donald Sutherland, Charles Cioffi, Roy Scheider, Dorothy Tristan, Rita Gam.

Synopsis:

A small-town detective searching for a missing man has only one lead: a connection with a New York prostitute.

Memorable Lines:

Jane Fonda as Bree Daniels: Men would pay $200 for me, and here you are turning down a freebie. You could get a perfectly good dishwasher for that. And for an hour… for an hour, I’m the best actress in the world, and the best fuck in the world.

Bree Daniels: Tell me, Klute. Did we get you a little? Huh? Just a little bit? Us city folk? The sin, the glitter, the wickedness? Huh? Donald Sutherland as John Klute: Ah… that is so pathetic.

Extras:

- The first installment of what informally came to be known as Pakula’s Paranoia Trilogy. The other two films in the trilogy are The Parallax View (1974) and All the President’s Men (1976).

- According to her autobiography, Jane Fonda hung out with call girls and pimps for a week before beginning this film in order to prepare for her role. When none of the pimps offered to “represent” her, she became convinced she wasn’t desirable enough to play a prostitute and urged the director to replace her with friend Faye Dunaway.

- Jane Fonda said that she had to throw up while preparing for the scene where Bree goes through photos of dead prostitutes to identify her friends. She actually had gone to the city morgue too and it came as a great shock.

Critics:

- “Klute” showed the world Jane could act (though I always knew she could). – Jim Gordon, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- “Klute” is Fonda’s movie, and both Pakula and Sutherland seem to recognize that. It is not an argument in favor of sex work per se, even though it does the necessary service of combating the cliches and stigmas around the practice. But Fonda’s Oscar-winning performance as Bree does argue for a fullness of character – and of womanhood – that feels radically open to different possibilities and a wide spectrum of emotional experiences, including moments during therapy where she expresses uncertainty about her future and the choices she’s made. – Scott Tobias, The Guardian

END OF PART 1

Stay Tuned for the Top Ten Films of 1971 in PART 2 of our series which proves to be both mind boggling and hopefully educational.

If readers have a favorite that’s not listed in Part One or Two, no doubt you can access it on Feature Film, Released between 1971-01-01 and 1971-12-31 (Sorted by Popularity Ascending) – IMDb.

Send us your own list, at ed****@Tr**********.com and we will publish it in our Readers’ Poll.