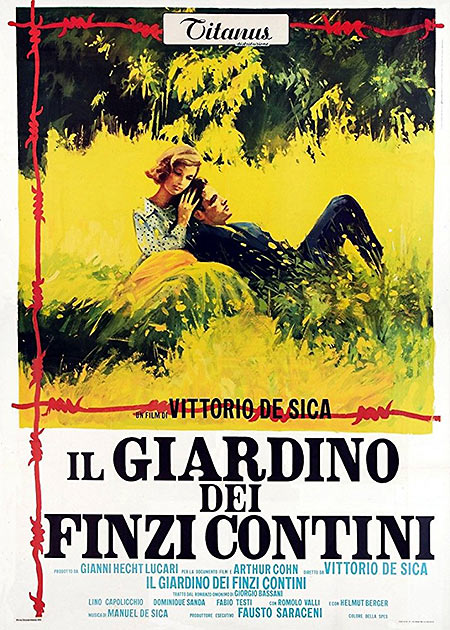

Directed by: Vittorio De Sica

Directed by: Vittorio De Sica

Writing Credits: Giorgio Bassani (novel), Vittorio Bonicelli, Ugo Pirro

Cinematography by: Ennio Guarnieri

Cast: Dominique Sanda, Lino Capolicchio, Helmut Berger, Romolo Valli

The Garden of the Finzi-Continis

By Walt Mundkowsky

I have never been able to get behind director Vittorio De Sica as much as the critical consensus tells me I should. His neorealist classics — Shoeshine, The Bicycle Thief, Umberto D. — seem to me flaccid, concerned with whipping up pathos to the exclusion of all else, and not always employing the most respectable means. When he made The Roof in 1956, it became clear that neorealism had reached a dead end; if he continued directing, it would be apart from the movement which had brought him to prominence.

De Sica went big on stars and budgets. He acquired a reputation as the only director who could get interesting, valid performances out of Sophia Loren, most notably in Two Women and Marriage Italian Style. Since then his work has a uniform awfulness — contemporary young love (A Young World), Peter Sellers laboring (After the Fox), Shirley MacLaine’s minuscule range (Woman Times Seven), sentimental marshmallows 30 years out of date (A Place for Lovers, Sunflower). The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (Cinema V) has been widely hailed as his return, but is one more maladroit stab at an emotional workout.

The film is based on the Giorgio Bassani novel — not really a novel, but an undisguised personal memoir. Bassani recalls his difficult youth as a middle-class Jew in Ferrara in 1938; the anti-Semitic laws bring him into close contact with the Finzi-Continis, a family of aristocratic, wealthy Jews. He details his frustrating, painful non-affair with Micol, the beautiful, aloof Finzi-Contini daughter. The book is hardly a narrative in any important sense; an epilogue tells us how the characters fared: Alberto, Micol’s consumptive brother, finally died; Micol and her family were taken to a concentration camp; Malnate, a leftist friend of Giorgio’s, never returned from the Russian front.

The film is based on the Giorgio Bassani novel — not really a novel, but an undisguised personal memoir. Bassani recalls his difficult youth as a middle-class Jew in Ferrara in 1938; the anti-Semitic laws bring him into close contact with the Finzi-Continis, a family of aristocratic, wealthy Jews. He details his frustrating, painful non-affair with Micol, the beautiful, aloof Finzi-Contini daughter. The book is hardly a narrative in any important sense; an epilogue tells us how the characters fared: Alberto, Micol’s consumptive brother, finally died; Micol and her family were taken to a concentration camp; Malnate, a leftist friend of Giorgio’s, never returned from the Russian front.

If Bassani’s book fails to satisfy, it’s because it stays unfulfilled. He wants to do justice to these people whom he knew — a noble sentiment, and Bassani is elsewhere a gifted writer. Here he denies himself elaboration and invention. Because he is his own protagonist, the story is inevitably tainted with Sensitive Youth Syndrome. But the book has a solid sense of perspective — it never pretends to be more than it is — and an air of straightforward truth-telling. The movie has neither.

Bassani’s prose is dry to a fault, at least in translation, while De Sica errs mightily in the opposite direction. Behind the opening credits is a montage of branches and leaves; they slip in and out of focus, and often the sun glints on the camera lens. The colors are the fruitiest imaginable — overripe oranges and yellows, artfully diluted blue-greens. In short, exactly the kind of knee-jerk Lyricism common to TV commercials. De Sica also overuses the zoom, which as usual has that boi-ingg effect, an arrow fired to reinforce the theatrics. The means of expression are disproportionate to what is being expressed, as good a working definition of the sentimental as any. To choose only one example out of dozens: Micol invites Giorgio to the Finzi-Contini home, and he goes bursting with expectation; when he arrives, a servant tells him that she has left. De Sica resorts to, of all things, a grandiose crane shot showing Giorgio turning his back to the camera and walking forlornly away. The editing is insecure; the incessant cutting to reaction shots — another reminder of TV — makes the film interminable and mawkish. De Sica has favored heavy, sobbing music before, and this effort (by his son Manuel) keeps getting in the way.

None of the genuine ambiguity in Bassani’s tale survives. In his anguish over Micol’s rejection of him, Giorgio imagines that she and Malnate are lovers. In the epilogue the author admits, “So what was there between the pair of them? Nothing? Who can tell.” But that will not do for De Sica. He has Giorgio spy on Micol and Malnate (the self-consciously arranged lighting piles one more fakery on this fake scene) just after they have made love; she notices Giorgio and gloatingly flaunts her nakedness.

Bassani shrinks from putting the death camps into his story, and the epilogue is all the more effective for his reticence; the simplicity of those last pages is moving because Bassani is humane enough not to pound away at us. It’s effective because he isn’t after a big, “effective” finish. De Sica doesn’t trust us as much as that. His film goes on from where the book ends to include scenes of Italian Jews being rounded up. As the Finzi-Continis are taken away, shots of their mansion receding into the distance are intercut with close-ups of Micol, her eyes swimming with tears.

Then there’s the dog, or rather the car rolling past the huge, spotted Finzi-Contini dog chained up at the side of the road, as the weeping strings submerge everything in aural muck. The film operates at a level of understanding where the sad-eyed dog is the ideal symbol. A stagey diatribe on Dachau (“It’s a hotel in the woods. One hundred chalets … rooms without baths … a single latrine”) plays off our knowledge of the camps against Giorgio’s ignorance so nudgingly and smugly that its motivation should be questioned. We need films that enlarge us, not ones which feed ill-founded superiority complexes. The film closes, after a lumpily edited montage of Ferrara’s deserted streets, on the Finzi-Contini tennis courts overwhelmed by weeds.

Then there’s the dog, or rather the car rolling past the huge, spotted Finzi-Contini dog chained up at the side of the road, as the weeping strings submerge everything in aural muck. The film operates at a level of understanding where the sad-eyed dog is the ideal symbol. A stagey diatribe on Dachau (“It’s a hotel in the woods. One hundred chalets … rooms without baths … a single latrine”) plays off our knowledge of the camps against Giorgio’s ignorance so nudgingly and smugly that its motivation should be questioned. We need films that enlarge us, not ones which feed ill-founded superiority complexes. The film closes, after a lumpily edited montage of Ferrara’s deserted streets, on the Finzi-Contini tennis courts overwhelmed by weeds.

Two actors shine through the prevailing trashiness. Lino Capolicchio conveys the intellect and vulnerability of Giorgio quite well; he’s not as technically varied as he might be, but it would have helped if De Sica had not kept pushing his camera up against him. Romolo Valli is always reliable, and he gives Giorgio’s father, a Jew who joined the Fascist party and keeps saying that things are not as bad as they seem, a pungent sense of misguided authority.

Read Bassani’s book instead.

Editor’s note: Due to the recent Neo-Nazi riots in Charlottesville, The Garden of the Finzi-Continis today seems as timely as it did in 1971.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Joshua May

January 22, 2021 at 7:39 am

Thanks for this review. It encapsulated and articulated so well the things that disappointed me about the movie, but that I had trouble putting my finger on as well as you have done.