Shall we just get the pleasantries out of the way? Capri is a lovely little island that floats in the turquoise waters of the Gulf of Naples and where the air is scented with bougainvillea that tumbles in wild abandon over the garden walls of white-washed villas. Blah, blah, blah. Not that I’m immune to the natural beauty of this island, and I have enjoyed many long walks beneath pine trees out to Punta Tragara and refreshing dips beneath the sea cliffs at the Faraglioni, but on this rock it’s the human fauna, warts and all, that I find to be especially intriguing.

Capri, you see, has long attracted bohemians, libertines, and the outright scandalous. The novelist D.H. Lawrence grumpily complained that the island was “a gossipy, villa-stricken, two-humped chunk of limestone that does heaven much credit but mankind none at all.” I lean toward amused fascination, not despair, about humankind when I sit in the Piazzetta, the main square of Capri Town. Day trippers troop through, water bottles in one hand, iPhones at the ready for selfies in the other, and alongside them are leggy models who strut around as if on a Milan runway, a scattering of lotharios, easy to spot in rumpled linen, and many well-dressed, cappuccino-drinking bon vivants who might be accountants and marketing execs in real life but in this setting become flaneurs and flaneuses. The writer Joseph Conrad also got carried away with the island’s undercurrents when, quite possibly sitting at a cafe table in this square, he wrote, “The scandals of Capri — atrocious, unspeakable, amusing scandals, international, cosmopolitan, and biblical flavored with Yankee twang and the French phrases of the gens du monde mingle with the tinkling of guitars in the barber’s shops.”

Capri has been synonymous with licentiousness since the Emperor Tiberius took up residence in a cliff-top palace in A.D 26. According to contemporary reports, he engaged in “depravities . . . so flagrant one can scarcely bear to report or hear them.” But since no one can resist passing on some good dish, especially about a public figure, news soon spread that the dark and mercurial emperor was having lovers of whom he’d tired hurled off the cliffs. Another dissolute, the Baron Jacques d’Adelsward-Fersen, took up residence in a villa a little way down the same hillside in 1905. He came to the island after some time in prison for an episode involving schoolboys, and he brought with him his lover, Nino Cesarini, a model for erotic photographs and paintings. The baron spent his time writing really bad verse and almost unreadable stream of consciousness prose, but he excelled at taking debauchery to extremes. He died while sipping cocaine-infused Champagne in a room he had designed to resemble a Chinese opium den. Nino did well for himself after the baron’s death and opened a bar and newsstand in Rome with the money he inherited.

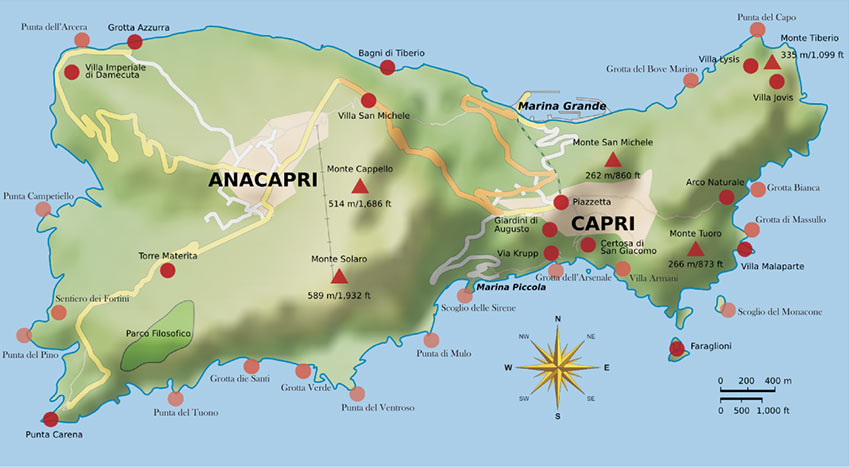

Probably the island’s most famous scandal is the one associated with Friedrich Alfred Krupp, the German steel and arms manufacturer. Money and power could not silence reports of Krupp’s orgies and other dalliances on Capri, and he committed suicide in 1902 when faced with a trial and many years of hard labor. He’s lent his name to the beautiful Via Krupp, a steep lane of switchbacks that connects the Giardini di Augusto, designed and financed by Krupp, with Marina Piccola, where he moored his two yachts. Amidst the garden’s lush greenery stands a statue of Vladimir Lenin. The revolutionary and first premier of the Soviet Union seems a bit out of place in such luxuriant and hedonistic surroundings, but he admired the island when he stayed here as a guest of his co-patriot, the writer Maxim Gorky, in 1908.

It would be easy to go on and on gossip-mongering, but it seems only fair also to mention some island residents who have been above reproach, or almost. Axel Munthe, a Swedish physician and ornithologist, is still the island’s golden boy, having settled into the airy and enchanting Villa San Michele in 1887. Oh, you could dig up a few skeletons in the doctor’s closet, like his lifelong devotion to Princess Victoria (later Queen) of Sweden, to whom he prescribed spending a lot of time in his company on Capri. All in all, though, Munthe is an uplifting character, and he was beloved for some truly altruistic acts, like treating poor islanders for free, coming to the aid of Neapolitans during a cholera epidemic, and taking in a menagerie of stray animals. Plus, he penned some pretty memorable thoughts, like “The soul needs more space than the body.” That will make perfect sense when you take in the views of this legendary island from the airy and light-filled rooms where Munthe spent most of his life.