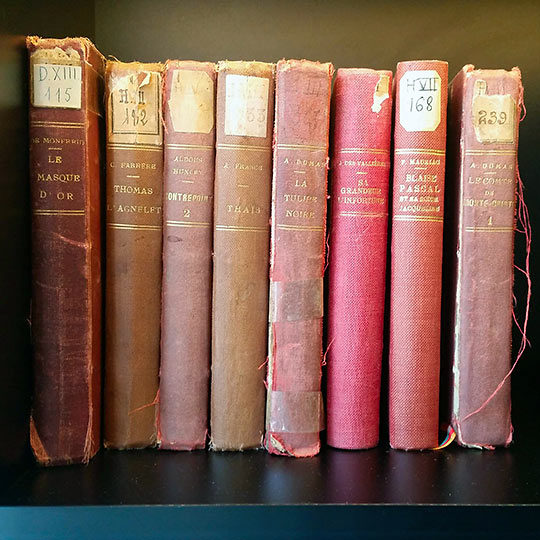

In the Hotel Rotary Geneva, a tattered Alexandre Dumas looks down on the lobby. Random threads, torn and frayed, hang down like old hairs on a corpse. The faded gold lettering of Le Comte de Monte Cristo is barely visible beneath a library decal peeling off the spine, but Dumas commands attention, perched like royalty next to Aldous Huxley, Blaise Pascal and Thaïs the holy courtesan. In more cubby holes, a dilapidated Stendhal leans against Les Contes de Jacques Tournebroche. Napoleon’s political views accompany Les Hommes de bonne volonté, part nine. A litany of giants beckons me here in Geneva, where much unfolds beneath the bureaucrats, if you just know where to look.

In the Hotel Rotary Geneva, a tattered Alexandre Dumas looks down on the lobby. Random threads, torn and frayed, hang down like old hairs on a corpse. The faded gold lettering of Le Comte de Monte Cristo is barely visible beneath a library decal peeling off the spine, but Dumas commands attention, perched like royalty next to Aldous Huxley, Blaise Pascal and Thaïs the holy courtesan. In more cubby holes, a dilapidated Stendhal leans against Les Contes de Jacques Tournebroche. Napoleon’s political views accompany Les Hommes de bonne volonté, part nine. A litany of giants beckons me here in Geneva, where much unfolds beneath the bureaucrats, if you just know where to look.

The lobby opens into a welcoming restaurant where even more old volumes follow the wall, continuing far beyond the bohemian lamps, art deco trimmings, limestone flooring and framed antique mirrors. In the spacious eatery, hotel guests and locals harmonize the opposing forces of contemporary décor and classic accoutrements, as if they, themselves, are the fortifying ingredients in some strange act of Jungian alchemy. In that sense, Carl Gustav Jung would be proud. I can almost imagine him in the corner, whispering into his mustache, just as I’m starting to do myself.

As John Berger wrote, Geneva is a place of convergence. For centuries travelers passing through here have left letters, instructions, maps, lists and messages for Geneva to relay to other travelers arriving later. Geneva is a library archive of human predicaments. She stores them all with a mixture of curiosity and pride, wondrous if not indifferent, but nevertheless impressed with the variety of people that landed in her lap. It’s a great town for me to sift through the psychological remnants of authors that preceded me.

These days, of course, Geneva is more known for international peacemaking vibes and financial networks. The United Nations headquarters are here. So is the Red Cross and the World Health Organization. Sheikhs, oligarchs and spies are probably here everywhere too. If I want to see a white Rolls Royce with Qatari plates, I don’t have to venture very far from my hotel.

There is more, however. Much more. Any sugary listicle would include Mont Salève, Jardin Anglais, the Carouge neighborhood or the Jet d’Eau, Geneva’s defining landmark, a fountain right in the middle of the lake, surrounded by majestic five-star hotels and views of the French Alps. One of those hotels, the Beau-Rivage, is perhaps Geneva’s most definitive accommodation. Across the street, right at the waterfront, sits a plaque devoted to Empress Elisabeth of Austria, aka Sisi, who was stabbed to death in 1898 by an Italian anarchist, just after Sisi left the Beau-Rivage.

This is more my kind of landmark. I have spent much of my adult life drilling beneath the bourgeoisie and surrendering to the gritty underside of history, both at home and abroad, going half-crazy and half-broke in the process. So, in Geneva, a bastion of luxury and wealth, this is where I go: beneath the bureaucrats. I am here alone on business — what little business I have left — and in Geneva I cannot seem to roam anywhere without the ghosts of artists, writers, painters, crooks and lecherous raconteurs reeling me in, even if a plaque was all it took. And nearly every block includes a plaque referencing a notable person who spent time there. What a beautiful way to experience a city — proof, I hope, that I made the right choice by not choosing anything in life except to keep writing and never give up. The dead have left their shadows in my path.

Five minutes down the street from the Hotel Rotary and across a cement pedestrian bridge over the Rhône, the tiny Île Rousseau is a classic meeting spot. Named after Jean-Jacques himself, the patch of land features a statue of the Swiss philosopher amid a cluster of colossal sycamores, their branches stretching out in all their fractal glory. A flower bed sits in front of the statue and a small makeshift coffee shop lurks a few feet away. The miniature island used to be a private garden for the Hotel des Bergues, the city’s first modern hotel circa 1834, and also the place where James Bond stayed for a night in the book, Goldfinger. It’s now a Four Seasons.

In the 19th century, a group of Russian anarchists lived at the nearby Hotel Russie overlooking this statue. Huge fans of Rousseau, they wanted a place to live where they could always see the man. The anarchists are long gone, as is the Hotel Russie, but Jean-Jacques remains. Everyone from Byron to Tolstoy traveled to Geneva specifically inspired by Rousseau. After reading Byron, Thomas Cook decided to start the world’s first travel agency, which, in turn, led to generations of Britons coming to Geneva. They all have Rousseau to thank.

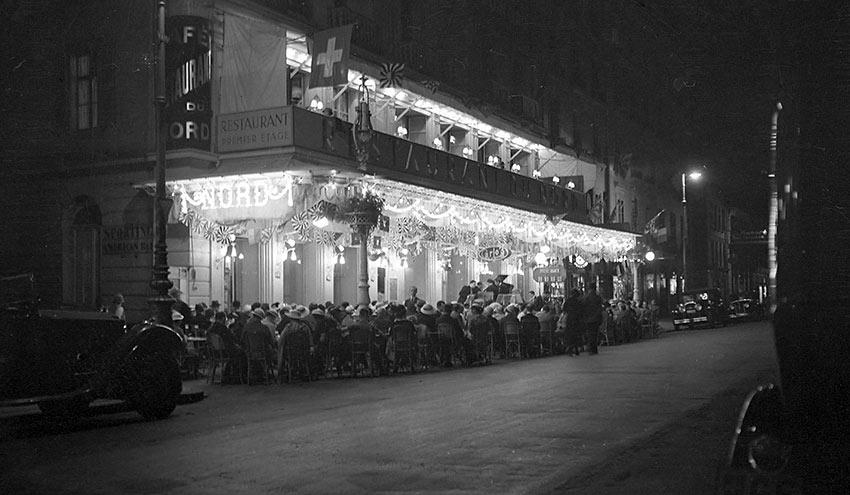

Across the water from here, in the 19th and 20th centuries, one would have found the old Café du Nord — “rendez-vous des étrangers” says an old guidebook — where the painter Gustave Courbet, along with fellow exiled French troublemaker, the journalist Henri Rochefort, would gather to drown their sorrows. Located inside the old Hotel de la Balance on Grand Quai, (today Quai Général-Guisan), Café du Nord attracted at one time or another the likes of poet Rainer Marie Rilke, theater director Georges Pitoëff, Hungarian writer Ferenc Molnár and the painter Alexander Archipenko. Molnár showed up at the end of the 19th century, as a journalist on assignment to cover the trial of Sisi’s assassin. He spent entire days in the Cafe du Nord. Lenin would visit him there. Molnár would later return in the 1930s, exiled from Hungary during the war. He wrote about the refugee life in his book, Companion in Exile.

Many more writers left legacies at Café du Nord. Oscar Wilde once showed up, after complaining that Mont Blanc was now a tourist trap, robbed of its splendor, with only spinsters ascending its heights. He disliked Switzerland, adding that the country produced nothing but theologians and waiters.

Many addresses in Geneva recall similar stories. Courbet, for example, even rented a shop near rues Chantepoulet & Cendrier, a few steps from my hotel, where he exhibited and sold his work, although the locals were indifferent.

Since the nearest one can get to the actual dead is in the cemetery, Berger and countless other scribes have made pilgrimages to the gravesite of Jorge Luis Borges in the Cemetery of Kings. Officially the Plainpalais Cemetery, the humble piece of land is located in the neighborhood of the same name, which is also the part of town where Frankenstein’s monster committed his first murder. Only people with specific connections to Geneva are allowed to be buried here. The Protestant Reformer John Calvin gets his own monument, but no one knows exactly where he’s buried. Other legends underneath the grass at Plainpalais include the composer Alberto Ginastera, the feminist writer Alice Rivaz and the conductor Ernest Ansernet.

The more I sink beneath the bureaucrats, the more ghosts begin to reveal themselves. Geneva was a town where exiled troublemakers came to print their pamphlets without being censored — Lenin, Machiavelli, Montaigne and Montesquieu especially. In fact, it seems like every taboo-shattering writer, composer, painter or journalist ostracized in their home towns wound up in Geneva at one point. The roll call includes: Franz Liszt, Gustave Courbet, Ian Fleming, Chateaubriand, Benjamin Disraeli, Gauthier, Somerset Maugham, Byron, Casanova, Voltaire, Colette, Victor Hugo, Nabokov, Stendhal, John Ruskin, Tolstoy and Carlos Fuentes. I only have time for a few of them, but Geneva makes me long to join that list.

Now, some people dismiss the use of past literary vibes to harmonize the current day. It’s a hallucination, they say. An illusion. The Geneva of today is not the Geneva in which these exiled raconteurs lived. That Geneva is long gone.

If so, then just sitting here next to dead authors on the shelves of the Hotel Rotary, I have fallen into Geneva’s trap. If it’s all a grand illusion, then I am coming on in to see what’s happening. I will surrender to the illusion. The dead can inspire me just like their living counterparts. Like Berger suggested, they have left me packets of instructions. Somewhere in this grand convergence I can find the ambition and the perseverance to keep writing and never give up.

Like Jan Morris once wrote of another city, Trieste, maybe I am seeing Geneva figuratively, not just as a city, but as an idea of a city. Her words apply here as well, since Geneva has a “particular influence upon those of us with a weakness for allegory — that is to say, as the Austrian Robert Musil once put it, those of us who suppose everything to mean more than it has any honest claim to mean.”

Musil, who is also buried in the Plainpalais Cemetery, arrived in Geneva at the beginning of WWII, living just long enough to see the Nazis ban everything he’d ever written back home in Austria. The Clinique des Grangettes property became his home, where he continued to work on the third part of The Man Without Qualities. He died in 1941.

To riff even more on Morris, I could spend my life sniffing the creative breezes of Geneva, especially in Place du Bourg-de-Four, the town’s oldest square. It was here that Courbet the eternal fugitive, and whose ghost I cannot seem to shake, spent time drinking away his days at La Clémence. Unfortunately, the current incarnation was shut down when I stopped by.

From Place du Bourg-de-Four, it’s only a two-minute walk down the cobblestones along rue Etienne Dumont, past a few galleries and high-end retail to Franz Liszt and Countess Marie D’Agoult’s House of Love. The current plaque mentions nothing of their scandalous affair. Marie dumped her husband to run off with Liszt, a relationship that produced their first child, Blandine, who was born while they lived at this flat. While living here, Liszt also taught at the conservatory and wrote a piano nocturne, Les Cloches de Geneve (The Bells of Geneva) to celebrate the birth of Blandine. To accompany the composition, Liszt added a line from Byron: “I live not in myself, but I become / Portion of that around me.”

With all of this in mind, I am sinking, and sinking, deep into the lobby of my hotel, perhaps deeper into oblivion, thinking about Byron’s quote. I live not in myself; rather, I become a portion of what’s around me. Bells ring in my head. Liszt was yet another creative migrant to whom I can relate, sitting in the Hotel Rotary, surrounded by shelved books, torn and frayed authors, library discards and faded volumes. I think even more of those who infiltrated Geneva before me, leaving messages and artifacts for me to explore: Stravinsky. Sir Horace Walpole. Nietzsche. Conan Doyle. Wagner.

My brain merges with dead authors and composers — on the streets, in buildings, on the shelves behind me. The universe is a library, like Borges wrote, and Geneva is an archive of exiled creative troublemakers, all of whom continue to cast their shadows, albeit now eclipsed by the bureaucrats, the $35 salads and the Rolls Royces. But I summon them all, nevertheless. This is my idea of Geneva and I’m sticking with it.

Matthias

April 25, 2019 at 9:34 am

Fantastic and in-depth article, Gary. I have learned a lot about the free thinkers, politicians etc. who lived or visited Geneva. This article will be may main source, when doing research about Geneva’s literature history.

Sylvia

April 25, 2019 at 10:54 am

Great article! Although I have spent a lot of time in Geneva, you’ve dug up quite a few details that are new to me.

토슈어인포

April 28, 2019 at 8:59 pm

I do believe all the ideas you’ve inttroduced too your post.

They are very convincing and can certainly work. Nonetheless, the posts are too quick for starters.

Could you please prolong them a little from

subsequeent time? Thanks for the post. https://www.tosureinfor.com/

Gary Singh

May 6, 2019 at 9:29 am

I should also thank my tour guide, Ursula Diem-Benninghoff, who supplied key historical background, enabling me to write about this adventure. Hats off to her!

free music

December 17, 2019 at 1:24 am

Do you mind if I quote a couple of your posts as long as I

provide credit and sources back to your website? My blog is in the

exact same niche as yours and my visitors would certainly benefit from some of the information you present here.

Please let me know if this okay with you. Cheers!