The genesis of our poll was highly influenced by Christina Newland’s thoughtful piece in BBC Culture, entitled, Why 1971 was an extraordinary year in film – BBC Culture

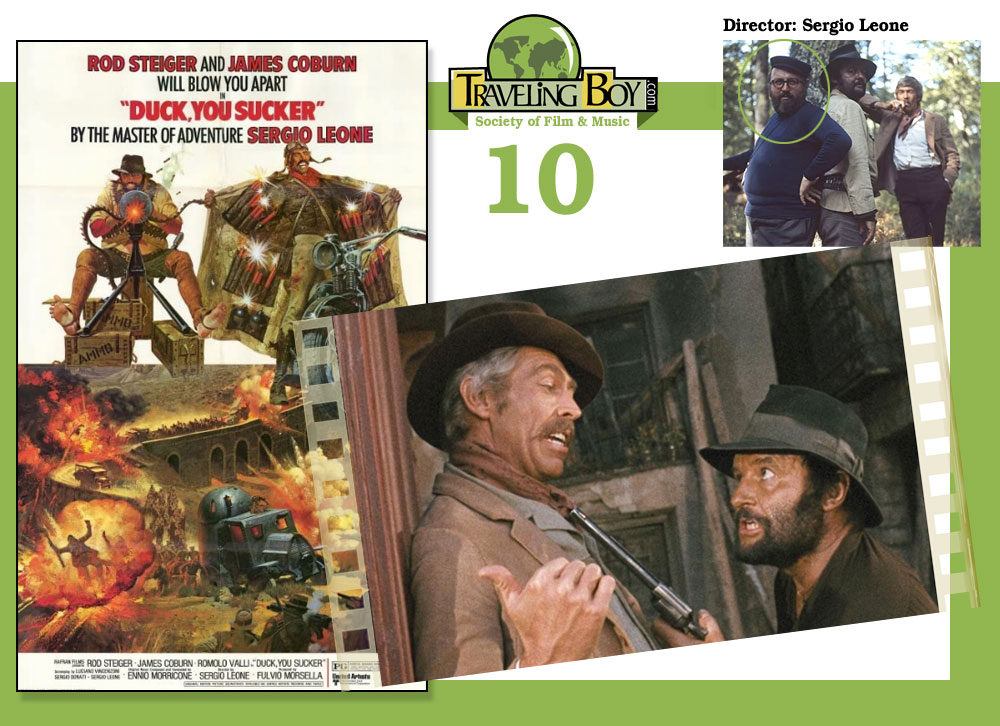

Number 10: Duck, You Sucker!

(aka Fistful of Dynamite)

Director: Sergio Leone; Writing: Luciano Vincenzoni, Sergio Donati, Sergio Leone; Cinematography: Giuseppe Ruzzolini; Music: Ennio Morricone.

Players: Rod Steiger, James Coburn, Romolo Valli, Maria Monti.

Synopsis: A Mexican bandit and an I.R.A. explosives expert rebel against the government and become heroes of the Mexican Revolution.

Memorable Lines:

- James Coburn as John H. Mallory: Where there’s revolution there’s confusion, and when there’s confusion, a man who knows what he wants stands a good chance of getting it.

- Mallory: When I started using dynamite… I believed in… many things, all of it! Now, I believe only in dynamite. I don’t judge you, Villega. I did that only… once in my life. Get shovellin’.

- Rod Steiger as Juan Miranda: Please, don’t try to tell me about revolution! I know all about the revolutions and how they start! The people that read the books, they go to the people that don’t read the books, and say “Ho-ho!” The time has come to have a change, eh?”

Behind the Scenes:

- When James Coburn was offered the role of John Mallory by Leone, he was initially reluctant. He had dinner with Henry Fonda (star of Once Upon a Time in the West) and asked him what he thought of Leone. Fonda told him that he considered Leone the greatest director he ever worked with. Coburn then took the part. Similarly, Fonda himself had been reluctant to take the part Leone offered him, but was persuaded by his friend, Eli Wallach, the co star of The Good, The Bad and Ugly (1966). Earlier, Wallach had asked Clint Eastwood what to expect when working with Leone on The Good, The Bad and Ugly. Eastwood replied, Never believe an Italian special effects man when he says the explosion won’t hurt you.

- The chanting of Shon shon shon in composer Ennio Morricone’s soundtrack was the suggestion of Leone’s wife, Carla Leone, who thought it would sound better than the original Wah wah chants. Morricone himself said the chants do not represent the names of characters but are just part of the soundscape like the chants in all the other Sergio Leone westerns. Morricone also said that Leone asked him to compose a film’s music before the start of principal photography – contrary to normal practice. He would then play the music to the actors during takes to enhance their performance.

- Rod Steiger demanded that his scenes be filmed with natural sound. This was virtually unheard of in Italian cinema and led to much tension between Steiger and Leone. Steiger had prepared for the role by taking accent and language lessons with a Mexican woman with the goal to use inflections that would imply Juan’s difficulty with speaking English instead of his native Spanish. To create Mallory accent, James Coburn vacationed in Ireland for five weeks. After the film’s completion, Steiger was content with the final result, and praised Leone for his skills as a director.

CRITICS:

- Underrated large canvas Leone; Steiger and Coburn as a revolutionary odd couple. – Dan King, T-Boy Film & Music

- Though not the towering masterpiece of “Once Upon a Time in the West” (1968), but still with Leone’s difficult to imitate directorial style of extreme closeups, generally followed by silence and violence (in this case explosions), and then cutting directly to sweeping panoramic shots of a scorched Spanish desert. And, Morricone, always on board, having contributed to all original musical compositions in Leone’s films since “The Colossus of Rhodes” (1961), including the Leone executive produced, “My Name is Nobody.” (1973). – Ed Boitano, T-Boy Film & Music

- Leone’s means are occasionally too complicated, his themes are rendered with a unique lyrical force as the leitmotifs of Morricone’s memory music. Thus, whereas the theme of “Once Upon a Time in the West” was revenge in all its ultimately futile ramifications, the theme of “Duck, You Sucker” is betrayal in all its hopelessly unresolved ambiguity. Leone is nothing if not ambitious and audacious, and I say more power to him in this era of emotionally paralyzed filmmaking. – Andrew Sarris, The Village Voice

Number 9: Macbeth

(Original title: The Tragedy of Macbeth)

Director: Roman Polanski; Writing: Roman Polanski, Kenneth Tynan, based on play by William Shakespeare; Cinematography: Gilbert Taylor; Film Editing: Alastair McIntyre; Production Design: Wilfrid Shingleton; Art Direction: Fred Carter; Set Decoration: Bryan Graves; Music: The Third Ear Band.

Players: Jon Finch, Francesca Annis, Martin Shaw, Terence Bayle, John Stride, Nicholas Selby, Stephan Chase, Paul Shelley.

Synopsis: A ruthlessly ambitious Scottish lord seizes the throne with the help of his scheming wife and a trio of witches in this chilling adaption of William Shakespeare’s play.

Memorable Lines:

- Jon Finch as Macbeth: False face must hide what false heart doth know.

- Francesca Annis as Lady Macbeth: Things without all remedy should be without regard. What’s done is done.

- Macbeth: Come, seeling night, scarf up the tender eye of pitiful day. And with thy bloody and invisible hand cancel and tear to pieces that great bond which keeps me pale. Light thickens, and the crow makes wing to the rooky wood. Good things of day begin to droop and drowse while night’s black agents to their prey do rouse

Behind the Scenes:

- Director Roman Polanski’s wife, actress Sharon Tate, was murdered by members of Charles Manson’s Family two years before the making of the film. It is believed that due to this traumatic event, Polanski developed the story to be a more violent representation of Shakespeare’s play. For instance, the scene in which Macbeth murders King Duncan was not in the original play and was instead implied.

- The scene in which Macbeth’s thugs massacre Macduff’s household was based on Roman Polanski’s memory of Nazi SS officers ransacking his house as a child.

- Filming began with four grueling weeks in Snowdonia National Park. Richard Vetter’s TODD-AO 35 lenses won an Academy Award for reducing anamorphic distortion in close-ups.

Critics:

- Polanski’s “Macbeth” is more interesting than if he had done your ordinary, respectable, awe-stricken tiptoe around Shakespeare. This is an original film by an original film artist, and not an “interpretation.” It should have been titled “Polanski’s Macbeth,” just as we got “Fellini Satyricon.” – Roger Ebert, rogerebert.com

- We’ve had remarkable film adaptions of Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” in the past with Orson Welle’s “Macbeth” (1948) and Akira Kurosawa’s “Throne of Blood” (1957) which both remained true to their own directorial sensibilities. This is also the case of Polanski’s adaptation where, in many respects, the images are jolted up to an almost hypnotic and hysterical level. Yes, the period detail and violence are profound; as it often was in the Middle Ages – Ed Boitano, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- People ask why I do things, this or that film. Why? Why do I eat fish and not steak for lunch? I don’t know why. There are layers of experience, and not only artistic experience. Making a film is separate from life, but it is made by a human being and whatever happens to me has got to have an influence in what I do. A film sums up the experiences of my life. You absorb the experience, you assimilate it and you make a decision. A film sums up everything—whom I see, what I drink, the amount of ice cream I eat. It is everything. Do you understand? Everything. – Roman Polanski, taken from interview with Bernard Weinraub of the NY Times after the release of Macbeth.

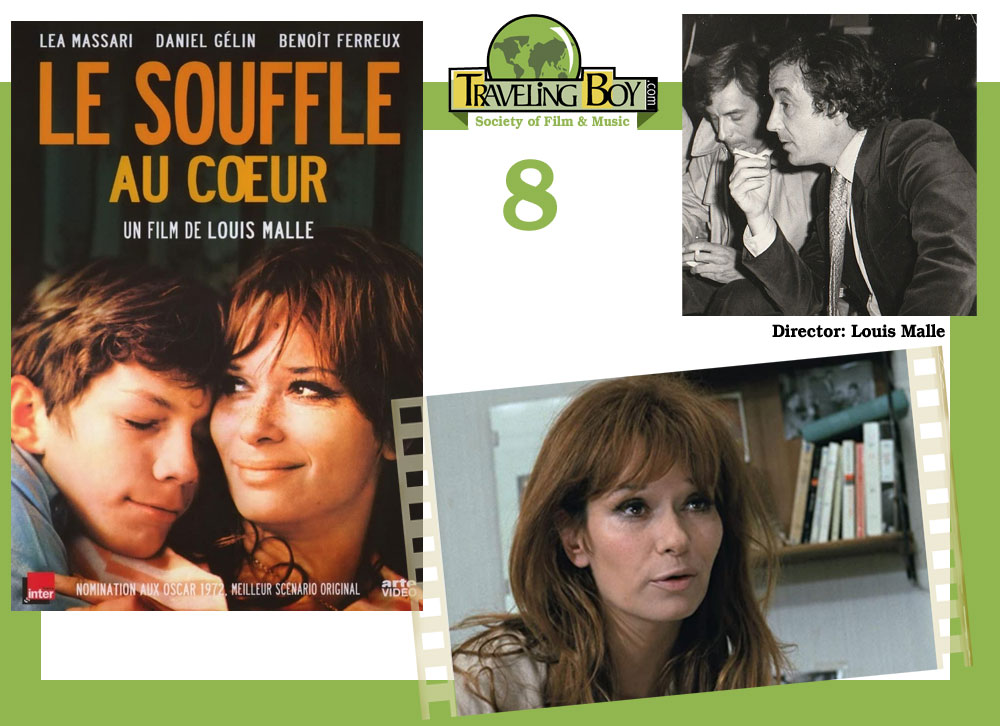

NUMBER 8: Murmur of the Heart (Le souffle au Coeur)

Director/Writer: Louis Malle; Cinematography: Ricardo Aronovich; Music: Sidney Bechet, Gaston Frèche, Charlie Parker, Henri Renaud.

Players: Léa Massari, Benoît Ferreux, Daniel Gélin, Michael Lonsdale, Ave Ninchi.

Synopsis: As France is nearing the end of the first Indochina War, an open-minded teenage boy finds himself torn between a rebellious urge to discover love, and the ever-present, almost dominating affection of his beloved mother.

Memorable Lines:

- Léa Massari as Clara Chevalier: I don’t know. Begin at the beginning. Wait to experience things yourself. And there’s plenty of time. I’m not rushing you. Everyone has to discover love for himself. Lots of things can happen between a man and a woman. Better to find out for yourself, not from a book.

- Benoît Ferreux as Laurent Chevalier: I’m tired of the old jazz. Always the same thing.

- Laurent Chevalier: The music store has the new Charlie Parker. Let’s go.

- Louis Malle based many aspects of the protagonist Laurent’s life on his own experiences growing up. This included his love of jazz, curiosity about literature, the “tyranny” of his two older brothers who tried to introduce him to sex, and having a heart murmur.

- While the incest aspects of the story were not autobiographical, Louis Malle did in fact end up sharing a hotel room with his mother as a child while on a trip to treat his heart murmur due to “bizarre” circumstances.

- Malle asserted in interviews that the incest, in particular, is fictional. He claimed that in writing the script, he had no intention to include incest, but ended up doing so as he explored an intense mother-son relationship

Critics:

- Breaking a taboo, ever so gently, is just part of the magic of this very French take on coming of age. – Stephen Brewer, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- “Murmur of the Heart” is mellow and smooth… but with the kick of a mule—a funny kick, which sends you out doubled over grinning.- Pauline Kael, The New Yorker.

- The boy is played by a nonactor, Benoit Ferreux, whose puzzlement about growing up, and whose admiration at the possibilities of life, remind us of young Jean-Pierre Leaud in Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows.” The two movies deserve comparison in more ways than one. And yet “Murmur of the Heart” isn’t really about the boy, but the mother. Lea Massari (you may remember her as the girl in “L’Avventura”) is so irrepressible, so irresponsible, so much a girl and not quite an adult, that her performance takes scenes that might have been embarrassing, and makes them simply magical. – Roger Ebert, rogerebert.com

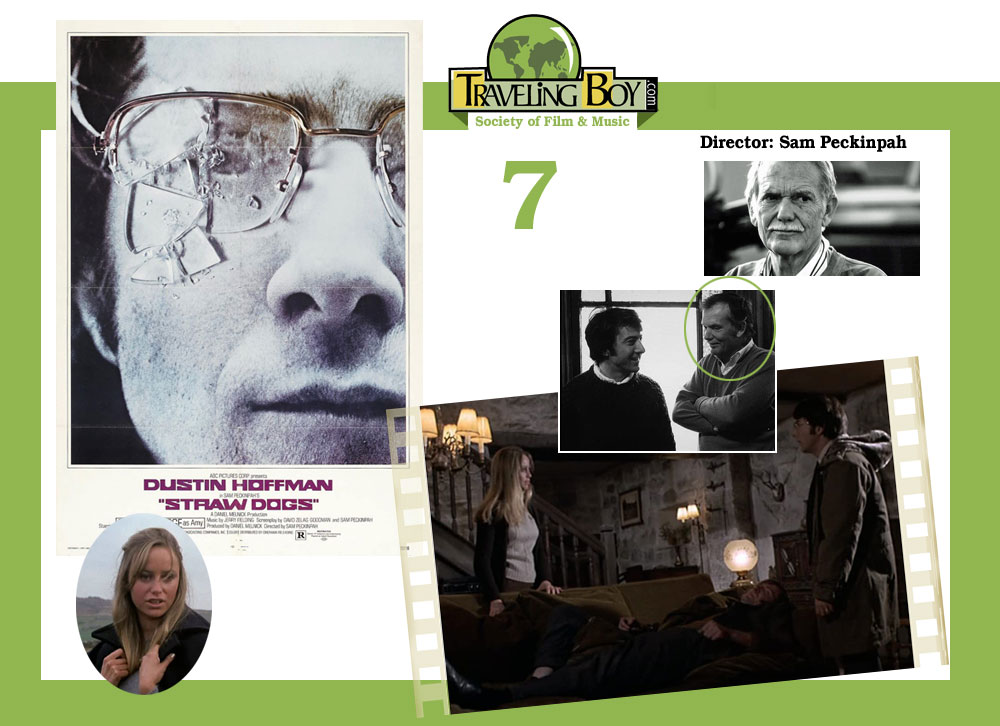

Number 7: Straw Dogs

Director: Sam Peckinpah; Writers: Sam Peckinpah, David Zelag Goodman, based on novel by Gordon M. Williams; Cinematography: John Coquillon; Music: Jerry Fielding; Film Editing: Paul Davies, Tony Lawson, Roger Spottiswood.

Players: Dustin Hoffman, Susan George, Peter Vaughan, T.P. McKenna, David Warner.

Synopsis: A young American man and his English wife come to rural England and face increasingly vicious local harassment.

Memorable Lines:

- Susan George as Amy Sumner: Those straw dogs were practically licking my body outside, so… Dustin Hoffman as David Sumner: I applaud their good taste. Amy Sumner: It’s not funny. David Sumner: We’ll, maybe you should wear a bra.

- David Sumner to brutes: Ok, you’ve had your fun. I’ll give you one more chance, and if you don’t clear out now, there’ll be real trouble. I mean it.

- David Warner as Henry Niles: I don’t know my way home. David Sumner (last line in film): That’s okay. I don’t either.

Behind the Scenes:

- Sam Peckinpah’s adaptation of the novel drew inspiration from Robert Ardrey’s books, African Genesis and The Territorial Imperative, which argued that man was essentially a carnivore who instinctively battled over control of territory.

- Before shooting, Sam Peckinpah instructed Dustin Hoffman and Susan George to live together for two weeks, with co-writer David Zelag Goodman in tow. Some of their interactions during this period were worked into the film’s script.

- In the scene where David Sumner (Dustin Hoffman) first enters the local pub, director Sam Peckinpah was unhappy with the other actors’ reaction to this stranger entering their world. Eventually, he decided to do one take where Hoffman entered the scene without his trousers on. He got his reaction, and these are the shots shown in the final film.

Critics:

- I can think of no other film which screws violence up into so tight a knot of terror that one begins to feel that civilization is crumbling before one’s eyes. – Tom Milne, Sight & Sound

- Sam Peckinpah’s “Straw Dogs” is the first American film that is a fascist work of art. The movie follows an American mathematician (Dustin Hoffman) and his wife (Susan George), who become the subject of an escalating series of attacks by a gang of locals; its graphic depiction of rape and murder crystallized the filmmaker’s worldview that humans are instinctively attuned to violence. – Pauline Kael, The New Yorker

- You have to understand, first of all, that the movie ends with maybe 20 minutes of unrestrained bloodletting, during which people are scalded with boiling whisky, have their feet blown off by shotguns, are clubbed to death and (in one case) nearly decapitated by a bear trap. The violence is the movie’s reason for existing; it is the element that is being sold, and in today’s movie market, it should sell well. But does Peckinpah pay his dues before the last 20 minutes? Does he keep us feeling we can trust him? I don’t think so. – Roger Ebert, rogerebert.com

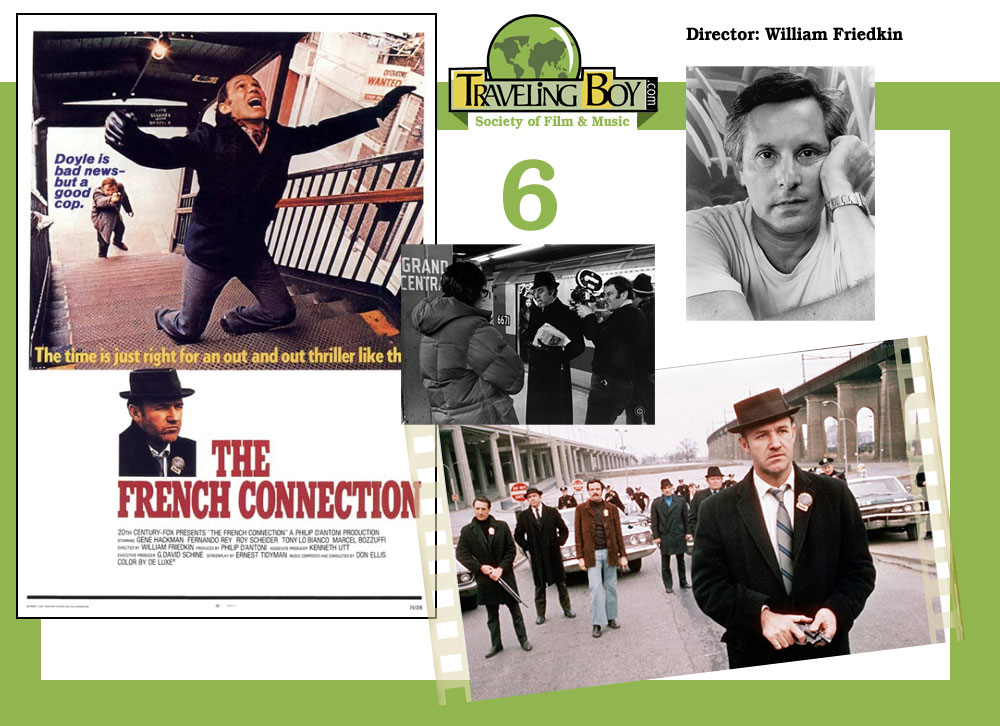

Number 6: The French Connection

Director: William Friedkin; Writing: Ernest Tidyman, based on the book Robin Moore; Cinematography: Owen Roizman; Music: Don Ellis; Editing: Gerald B. Greenberg; Art Direction: Ben Kasazkow.

Players: Gene Hackman, Roy Scheider, Fernando Rey, Tony Lo Bianco, Marcel Bozzuffi.

Synopsis: A pair of NYC cops in the Narcotics Bureau stumble onto a drug smuggling job with a French connection.

Memorable Lines:

- Gene Hackman as Jimmy ‘Popeye’ Doyle: All right, Popeye’s here! Get your hands on your heads, get off the bar, and get on the wall!

- ‘Popeye’ Doyle: Did you ever pick your feet in Poughkeepsie?

- Roy Scheider as Buddy ‘Cloudy’ Russo: Mulderig! You shot Mulderig! (a police detective). ‘Popeye’ Doyle (Ignoring him, last line in film): That son of a bitch is here. I saw him. I’m gonna get him.

Behind the Scenes:

- Cameras and equipment would often freeze during shooting due to near-freezing temperatures during the winter shooting in New York City and Brooklyn.

- According to William Friedkin, the film’s documentary-style realism through hand-held photography, use of real locations and editing style were inspired by the movies, Z (1969) by Costa Gavras, and Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless. (1960).

- The famous shot of the chase is made from a front bumper mount and shows a low-angle point of view shot of the streets racing by. Director of photography Owen Roizman, said that the camera was undercranked to 18 frames per second to enhance the sense of speed. Roizman’s contention is borne out when you see a car at a red light whose muffler is pumping smoke at an accelerated rate. Other shots involved stunt drivers who were supposed to barely miss hitting the speeding car, but due to errors in timing accidental collisions occurred and were left in the final film.

Critics:

- “The French Connection” answered the question, can Gene Hackman do anything bad? No, some films may not be great, but Hackman, always committed and solid. – Jim Gordon, T-Boy Society of Film & Music.

- The movie is all surface, movement, violence and suspense. Only one of the characters really emerges into three dimensions: Popeye Doyle’s Gene Hackman, a New York narc who is vicious, obsessed and a little mad. The other characters don’t emerge because there’s no time for them to emerge. Things are happening too fast. – Roger Ebert, RogerEbert.com

- A hugely successful slam-bang thriller that zaps the audience with noise, speed, and brutality. The movie, about police detectives tracking down a shipment of heroin in New York City, is certainly exciting, but that excitement isn’t necessarily a pleasure. The ominous music keeps tightening the screws and heating things up; the movie is like an aggravated case of New York. It proceeds through chases, pistol-whippings, slashings, murders, snipings, and more chases for close to two hours. This is what’s meant to give you a charge. – Pauline Kael, The New Yorker

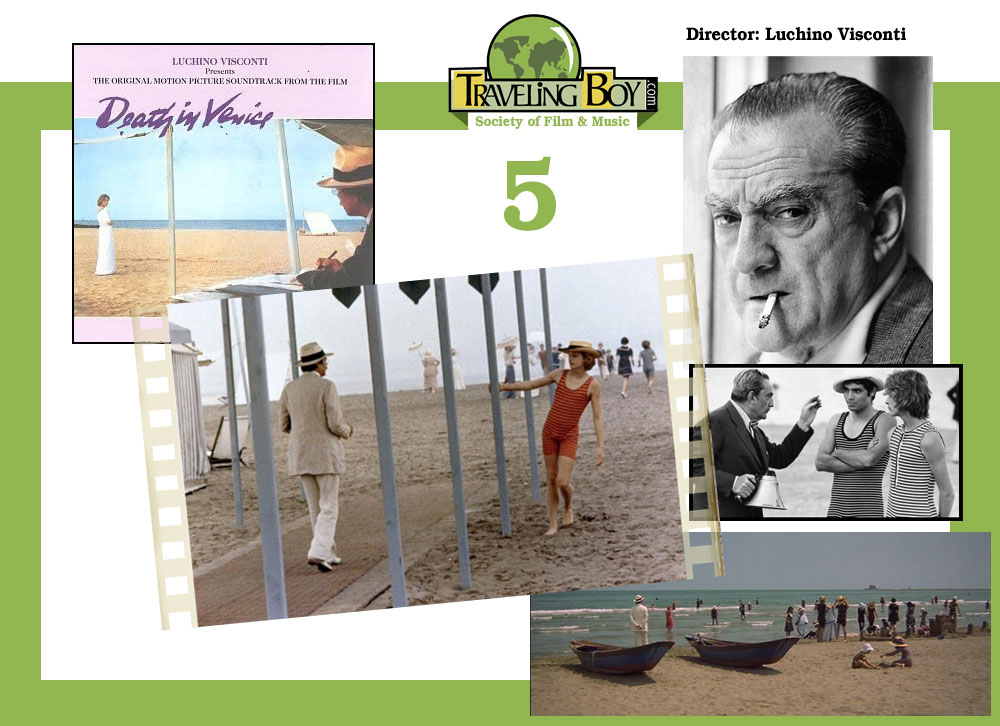

Number 5: Death in Venice

Director: Luchino Visconti; Writing: Luchino Visconti, Nicola Badalucco, based on novella by Thomas Mann; Cinematography: Pasqualino De Santis; Film Editing: Ruggero Mastroianni; Art Direction: Ferdinando Scarfiotti; Costume Design: Piero Tosi; Music: Gustav Mahler.

Players: Dirk Bogarde, Romolo Valli, Björn Andrésen, Silvana Mangano, Marisa Berenson, Mark Burns, Nora Ricci, Carole André, Franco Fabrizi.

Synopsis: In Visconti’s adaptation of the Thomas Mann novella, avant-garde Composer Gustav von Aschenbach travels to a Venetian seaside resort in search of repose after a period of artistic and personal stress. But he finds no peace there, for he soon develops a troubling attraction to an adolescent boy, Tadzio on vacation with his family. The boy embodies an ideal of beauty that Aschenbach has long sought and he becomes infatuated. However, the onset of a deadly pestilence threatens them both physically and represents the corruption that compromises and threatens all ideals.

Memorable Lines:

- Dirk Bogarde as Gustav von Aschenbach: You cannot reach the spirit with the senses. You cannot. It’s only by complete domination of the senses that you can ever achieve wisdom, truth, and human dignity.

- Gustav von Aschenbach: Madame, will you permit an entire stranger, to serve you with a word of advice and warning, which self-interests prevents others from saying. Go away! Go away, immediately. Don’t delay. Please, I beg you.

- Gustav von Aschenbach: You know sometimes I think that artists are rather like hunters aiming in the dark. They don’t know what their target is, and they don’t know if they’ve hit it. But you can’t expect life to illuminate the target and steady your aim. The creation of beauty and purity is a spiritual act.

Behind the Scenes:

- Second part of Visconti’s German Trilogy, which also included The Damned (1969) and Ludwig. (1973).

- In the Thomas Mann novella, Gustav von Aschenbach is an author, not a composer.

- While Gustav Mahler may have inspired the character of Gustav von Aschenbach, many of the plot points in the novella were inspired by Thomas Mann’s own experience. According to Mann’s widow Katia, the two were vacationing in Venice in 1911, when Mann noticed a beautiful young boy staying at their hotel.

Critics:

- Lots of self-obsessed pondering on beauty and intellect is set against a soundtrack by Mahler, with moody canals and crumbling palazzi as backdrops. – Stephen Brewer, T-Boy Society of Film & Music.

- While “Death in Venice” is indifferent to the plague (“Asiatic cholera”) as a condition in itself, the film’s intensive focus on its protagonist vividly raises the question of self-isolation. As the sole three-dimensional character, Aschenbach is necessarily solitary; his standoffish personality follows on this structural sequestration: he has to be a loner. Even in flashbacks to more gregarious times with wife and daughter, he is “a man of avoidance,” the “keeper of distances.” The friend who makes these charges gets even blunter: “You are afraid to have direct, honest contact with anything!” D. A. Miller, from My Lockdown with Death in Venice.

- The physical beauty of the film itself is overwhelming. The world of the Lido of sixty years ago has been re-created in painstaking detail. The fashions, the entertainments, the table settings reveal Visconti’s compulsion for accuracy. The photography is almost the first I have seen that is fully worthy of the beauty of Venice; the pink-and-gray city rises from waters of a glasslike smoothness, so that the water and the quality of light itself seem to suggest the presence of the plague-bearing sirocco wind. The wind brings both plague and beauty, which is its function in the Mann novel, and Visconti’s mastery of visual style almost succeeds in creating the very ideas and feelings that his heavy-handed narrative entirely misses. – Roger Ebert, RogerEbert.com

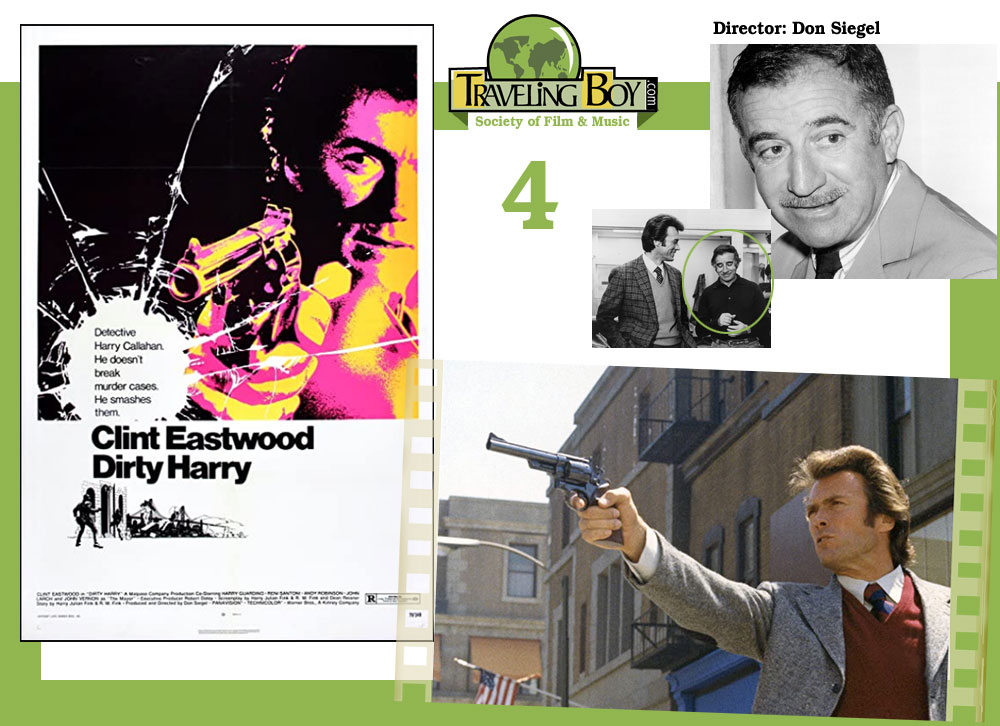

Number 4: Dirty Harry

Director: Don Siegel; Writing: Harry Julian Fink, R.M. Fink and Dean Riesner, based on story by Harry Julian Fink & Rita M. Fink; Cinematography: Bruce Surtees; Music: Lalo Schifrin; Film Editing: Carl Pingitore; Art Direction: Dale Hennesy; Makeup Department: Gordon Bau.

Players: Clint Eastwood, Andrew Robinson, Harry Guardino, Reni Santoni, John Vernon.

Synopsis:When a madman calling himself the Scorpio Killer menaces the city, tough-as-nails San Francisco Police Inspector Dirty Harry Callahan is assigned to track down and find the crazed psychopath.

Memorable Lines:

- Clint Eastwood as Harry Callahan: Now you know why they call me “Dirty Harry”…

every dirty job that comes along. - Harry Callahan: Uh uh. I know what you’re thinking. “Did he fire six shots or only five?” Well to tell you the truth in all this excitement I kinda lost track myself. But being this is a .44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world and would blow your head clean off, you’ve gotta ask yourself one question: “Do I feel lucky?” Well, do ya, punk??

- Harry Callahan: You know, you’re crazy if you think you’ve heard the last of this guy. He’s gonna kill again. Josef Sommer as District Attorney Rothko: How do you know? Harry Callahan: ‘Cause he likes it.

Behind the Scenes:

- Serial killer Scorpio was loosely based on the Zodiac Killer, who used to taunt Police and media with notes about his crimes, in one of which he threatened to hijack a school bus full of children. The role of Harry Callahan was loosely based on real-life detective David Toschi, who was the chief investigator on the Zodiac case.

- Before each of Harry’s three combative encounters with the Scorpio Killer, there is a cross and or a reference to Christ. The Scorpio Killer (Andrew Robinson ) wears a belt with a peace symbol buckle throughout the movie. According to producer and director Don Siegel, It reminds us that no matter how vicious a person is, when he looks in the mirror, he is still blind to what he truly is.

- Don Siegel ultimately directed Clint Eastwood in five films, and also appeared as an actor in Eastwood’s directorial debut, Play Misty for Me (also released in 1971).

Critics:

- Eastwood as the definite Siegel outsider struggling against the system. – Dan King, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- Dirty Harry” is very effective at the level of a thriller. At another level, it uses the most potent star presence in American movies — Clint Eastwood — to lay things on the line. If there aren’t mentalities like Dirty Harry’s at loose in the land, then the movie is irrelevant. If there are, we should not blame the bearer of the bad news. – Roger Ebert, RogerEbert.com

- Don Siegel’s cop movie was received as a right-wing fantasy on its release in 1971, and it probably made a lot of money on that basis. But now that the political context has faded, it’s easier to see the ambiguities in Clint Eastwood’s renegade detective-who, in the usual Siegel fashion, is equated visually and morally with the psychotic killer he’s trampling the Constitution to catch. A crisp, beautifully paced film, full of Siegel’s wonderful coups of cutting and framing.- David Kehr, Chicago Reader

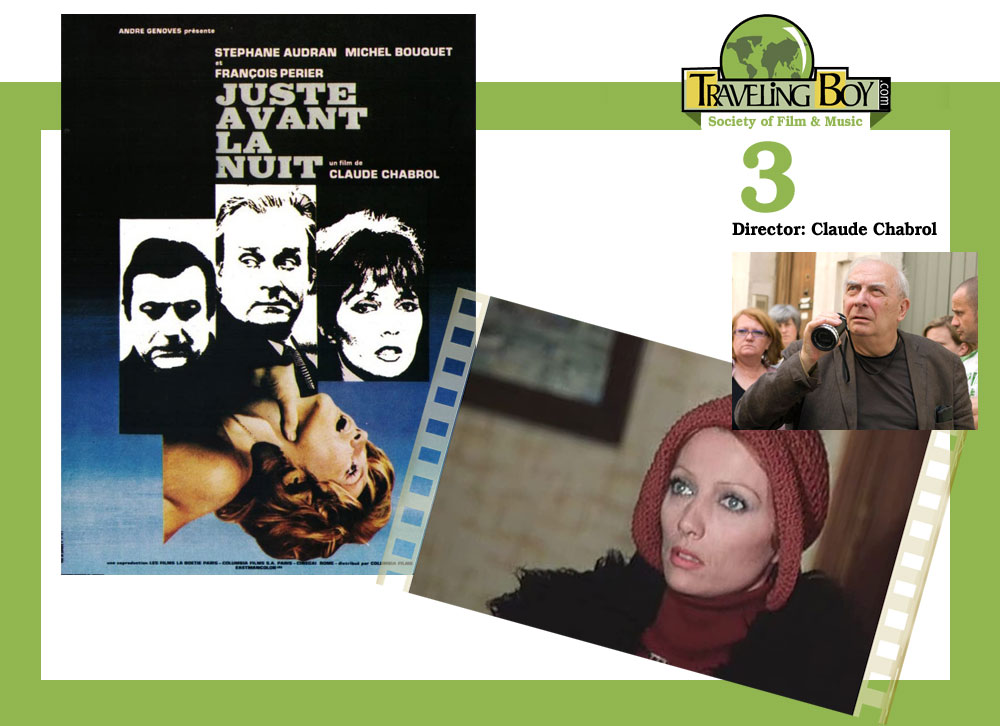

Number 3: Just Before Nightfall (Juste avant la nuit)

Director: Claude Chabrol; Writing: Claude Chabrol; based on Edouard Atiya’s crime novel, The Thin Line, later issued as Murder, My Love. Cinematography: Jean Rabier; Music: Pierre Jansen; Film Editing: Jacques Gaillard.

Players: Michel Bouquet, Stéphane Audran, Marina Ninchi , François Périer, Jean Carmet.

Synopsis: Charles Masson, an upper-class French advertising executive, is having an affair with Laura, the wife of his best friend. Charles strangles Laura when one of their S&M games crosses the line and she dies. Though reeking in remorse, Charles realizes that the police do not seem to have any clues about the crime, but has difficulties coping with the situation, trying to live a normal life with his two children and loving wife. Just Before Nightfall is another Chabrol film that focuses on infidelity and again it’s an intriguing drama and an excellent exploration of the human condition.

Memorable Lines:

- Michel Bouquet as Charles: My darling, I’d like you to understand. With you, love is simple and clear. With her it was a sort of…insane drama. She forced me…she made me participate. It wasn’t love, it was violent and humiliating. She wanted me to rape her. She forced me to be brutal to her. That’s what was so horrifying… it was she who tortured me and took pleasure in seeing me suffer.

- Charles: Justice doesn’t spare a guilty man because his family will suffer.

- Charles: I confessed. I unburdened my conscience. And you absolve me. I could have committed suicide. It would have been better for all. But I would’ve been a coward… a coward.

Behind the Scenes:

- This is the last film of Claude Chabrol’s Hélène cycle, in which actress Stéphane Audran starred, playing characters called Hélène in La femme infidèle (1969), Le Boucher (1970), and La Rupture (1970).

- Stéphane Audran appeared in 24 Chabrol films. In 1964 they were married which lasted for 16 years until divorce.

- Claude Chabrol, initially a film critic for Cahiers du Cinema, became one of the cornerstones of the French Nouvelle Vague.

Critics:

- Former French film critic Claude Chabrol is the ultimate Hitchcockian director, but with a profound Gallic twist. Along with Éric Rohmer, he wrote the very first book about the Master of Suspense: ‘Hitchcock – The First Forty-four Films.’ Like the Beatles and the British Invasion, who taught North Americans about their own music, the French Nouvelle Vague directors made us appreciate our own Hollywood films. Unlike Brian De Palma, Chabrol used his Hitchcockian influences as a starting point to transcend his own style and meaning. And, of course, there is a Hitchcock thing called, ‘Guilt.’ – Ed Boitano, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- His (Chabrol’s) characters are the molds from which the French bourgeoisie is cast. They’re terribly respectable, they live in comfortable homes and work in well-paying professions, they present a facade of total respectability. But underneath there are dark passions and well-kept secrets and, frequently, the ultimate embarrassment of murder. They aren’t killers; that’s the whole point. They’re people who commit murder to their own astonishment. – Roger Ebert, rogerebert.com

- One of the great films of the 1970s, this is Chabrol’s most representative film, and arguably his masterpiece. The first moments of the movie, with the camera intruding upon a blinds-drawn window, again invites comparisons with Hitchcock, and the opening shot of “Psycho.” But that tip of the hat only serves to underscore the extent to which Chabrol has moved on, as “Just Before Nightfall” situates us in a fully realized and now plainly recognizable Chabrolian universe. – Jonathan Kirshner, Bright Lights Film Journal

Number 2: A Clockwork Orange

Director: Stanley Kubrick; Writing: Stanley Kubrick, based on Anthony Burgess dystopian satire novel; Cinematography: John Alcott (lighting cameraman); Film Editing: Bill Butler; Production Design: John Barry; Costume Design: Milena Canonero; Music: Wendy Carlos, electronic music, realized by Walter Carlos.

Players: Malcolm McDowell, Patrick Magee, Michael Bates, Warren Clarke.

Synopsis: In the future, a sadistic gang leader is imprisoned and volunteers for a conduct-aversion experiment, but it doesn’t go as planned.

Memorable Lines:

- McDowell as Alex: There was me, that is Alex, and my three droogs, that is Pete, Georgie, and Dim, and we sat in the Korova Milkbar trying to make up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening. The Korova milkbar sold milk-plus, milk plus vellocet or synthemesc or drencrom, which is what we were drinking. This would sharpen you up and make you ready for a bit of the old ultra-violence.

- Alex: It had been a wonderful evening and what I needed now to give it the perfect ending was a bit of the old Ludwig van.

- Alex: So I waited. And O, my brothers, I got a lot better, munching away at eggi-wegs and lomticks of toast and lovely steaki-wakes. And then one day, they said I was going to have a very special visitor.

Behind the Scenes:

- Because of the limited budget, various techniques had to be used such as dolly shots on wheelchairs, sound recorded live on set, the use of natural light and some scenes in handheld cameras. However, at that time the new camera zoom control was first used in the picture.

- Malcolm McDowell’s eyes were anesthetized for the torture scenes so that he would film for periods of time without too much discomfort. Nevertheless, his corneas got repeatedly scratched by the metal lid locks.

- The film was unavailable for public viewing in the UK from 1973 until 2000, due to Kubrick and Burgess death threats. British video stores were so inundated with requests for the movie that some took to putting up signs that read: No, we do not have “A Clockwork Orange” It was released the year after Stanley Kubrick’s death.

Critics:

- Whereas Altman’s style was loose and free, Kubrick was the new visionary whose attention to detail in every aspect of his film rivaled that of Hitchcock. Where Altman pulled his audiences in with small, nuanced answers, Kubrick pushed his audiences with big bold questions. Kubrick saw a dystopian future where government gaslighted and conditioned the minds of the youth, ironically set to classic works by Beethoven and Purcell. “Clockwork” is a nightmare, but never a horror. Mike Rand, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- Stanley Kubrick’s ninth film, “A Clockwork Orange,” which has just won the New York Film Critics Award as the best film of 1971, is a brilliant and dangerous work, but it is dangerous in a way that brilliant things sometimes are. -Vincent Canby, New York Times

- “A Clockwork Orange” manifests itself on the screen as a painless, bloodless, and ultimately pointless futuristic fantasy. The first third splashes out of a wide-angle lens like a madly mod picture-spread for Look magazine where Kubrick toiled briefly long, long ago. The middle third provides a moderately engrossing indictment of B. F. Skinnerism in action. But the last third of the movie is such a complete bore that even audiences of confirmed Kubrickians have drowned out smatterings of applause with prolonged hissing. – Andrew Sarris, The Village Voice

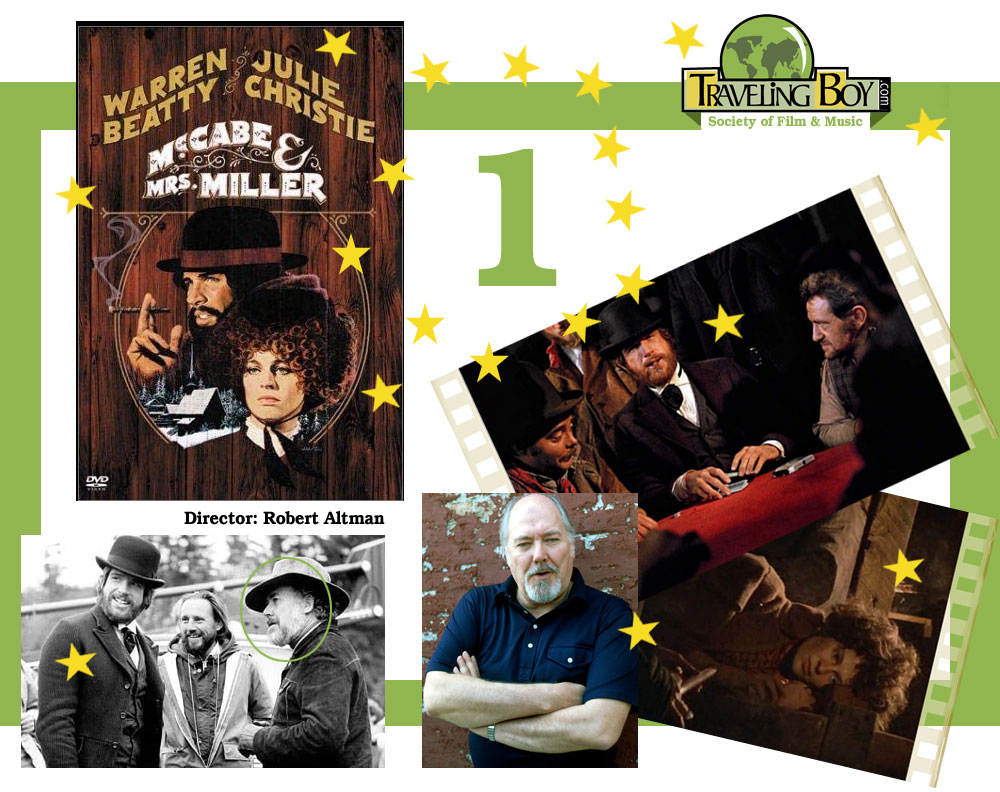

Number 1: McCabe & Mrs. Miller

Director: Robert Altman; Writing: Robert Altman and Brian McKay, based on novel McCabe (1959) by Edmund Naughton; Cinematography: Vilmos Zsigmond; Film Editing: Lou Lombardo; Music: Leonard Cohen; Production Design: Leon Ericksen; Art Direction: Al Locatelli, Philip Thomas; Sound Department: John W. Gusselle.

Director: Robert Altman; Writing: Robert Altman and Brian McKay, based on novel McCabe (1959) by Edmund Naughton; Cinematography: Vilmos Zsigmond; Film Editing: Lou Lombardo; Music: Leonard Cohen; Production Design: Leon Ericksen; Art Direction: Al Locatelli, Philip Thomas; Sound Department: John W. Gusselle.

Players: Warren Beatty, Julie Christie, Rene Auberjonois, William Devane, John Schuck, Corey Fischer, Bert Remsen, Shelley Duvall, Keith Carradine, Michael Murphy, Hugh Millais.

Synopsis: A gambler and a prostitute become business partners in a remote Pacific Northwest mining town in 1902, and their enterprise thrives until a large corporation arrives on the scene.

Memorable Lines:

- Warren Beatty as John McCabe: I tell you, sometimes, sometimes when I take a look at you, I just keep looking and a-looking. I want to feel your body against me so bad, I think I’m going to bust. I keep trying to tell you in a lot of different ways. If just one time you could be sweet without no money around. I think I could – well, I’ll tell you something. I’ve got poetry in me. I do. I’ve got poetry in me!

- Julie Christie as Constance Miller: Listen, Mr. McCabe. I’m a whore, and I know a awful lot about whorehouses. And I know that if you had a house up here, you’d stand to make a lot of money. Now, this is all you’ve got to do: put out the money for the house. I’ll do all the rest. I’ll look after the girls, the business, the expenses, the running, the furnishing, everything. And I’ll pay you back any money you put in the house, so’s you won’t lose nothin’. And we’ll make it fifty-fifty.

- John McCabe: If a frog had wings, he wouldn’t bump his ass so much, follow me?

Behind the Scenes:

- For a distinctive look, Robert Altman and Vilmos Zsigmond chose to “flash” (pre-fog) the film negative before its eventual exposure, as well as use a number of filters on the cameras, rather than manipulate the film in post-production; in this way the studio could not force him to change the film’s look to something less compelling. However, this was not done for the final 20 minutes of the picture, as Altman wanted the danger to McCabe to be as realistic as possible. Note the change when McCabe wakes up, grabs a shotgun, and starts off to the church.

- Though the film takes place in the fictional town of Presbyterian, Washington State, it was actually shot outside of Vancouver, BC.

- During post-production, Altman was having difficulties finding a proper musical score, until he attended a party where the album Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967) was playing. He noticed that several songs from the album seemed to match the mood and themes of the movie. Cohen, who had been a fan of Altman’s previous film, Brewster McCloud (1970), allowed him to use three songs from the album: The Stranger Song – which Cohen added a bridge – Sisters of Mercy and Winter Lady. Altman was dismayed when Cohen later admitted that he didn’t like the movie. A year later, Altman received a phone call from Cohen, who told him that he changed his mind after re-watching the movie with an audience and now loved it.

Critics:

- A rich kaleidoscope of landscape, rain and smoke; a family of regular Altman players speaking in overlapping sound, accompanied by the haunting music of Leonard Cohen makes “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” feel like an opium induced dream.- Ed Boitano, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- Altman’s cool, loose style lets his camera lens roam in and out of the lives of his characters while his soundtrack captures every little nuance in the social landscape of the Pacific Northwest during the end of the Old West. Altman’s melting pot of sights and sounds is every bit as American as Ozu’s Tatami- style camera setup is Japanese. Without the flash of Scorsese or the drama of Coppola, Altman carved his footprints into America’s modern cinematic landscape. – Michael Rand, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

- Less Altman’s take on the Wild West than life in an isolated Wild West community. – Dan King, T-Boy Society of Film & Music

See The 20 Best Films of 1971, Part One

If you have a favorite film from 1971 and it’s not listed above, you can access it on IMDB’s Feature Films released between January 1, 1971 through December 31, 1971. (Sorted by Popularity Ascending)

Send us your own list, at

ad*@Tr**********.com

and we will publish it in our Readers’ Poll.